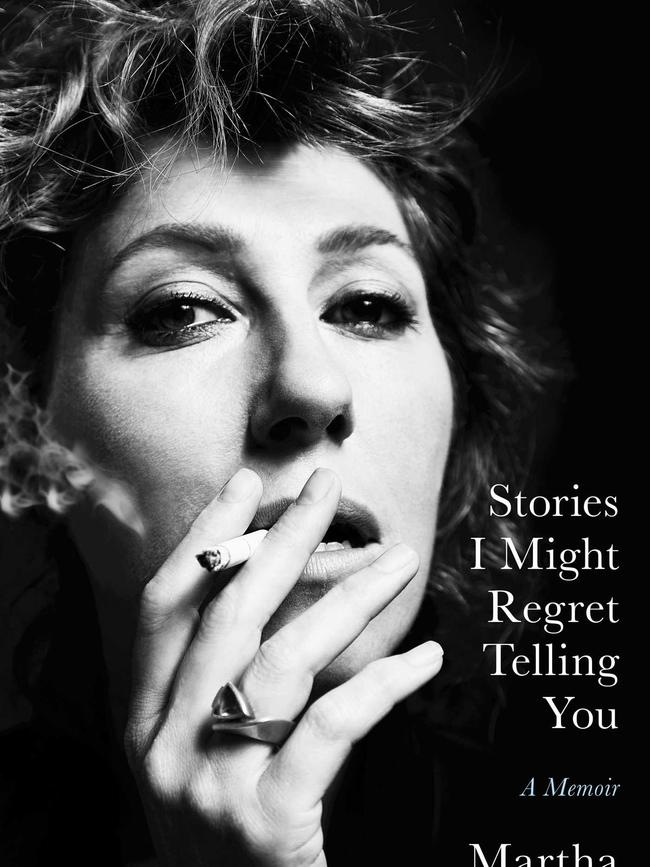

Martha Wainwright reveals the hole in her heart in memoir Stories I Might Regret Telling You

My dad told me when I was a teenager that he didn’t want me at first and pressured my mother to have an abortion. My mum freaked out just as the procedure was about to start.

I was born Martha Gabrielle Wainwright in New York State in 1976. My mother, Kate McGarrigle, and my father, Loudon Wainwright III, loved me – or at least they grew to love me. Loudon told me when I was a teenager that he didn’t want me at first and pressured my mother to have an abortion.

My mum freaked out just as the procedure was about to start, though, and the doctor spoke up. He was concerned for her and he pointed out that Loudon and Kate were married, had some degree of financial stability, and had one child already, my brother, Rufus. Maybe not the best reasons to bring a child into the world, but I’m glad the doctor opened his mouth.

I was surprised when Loudon told me this story, and it also hurt my feelings. I had always felt a little out of place in the world, and knowing that I’d only just barely made the cut didn’t help matters any. Perhaps he should never have told me.

I don’t think my mum would have. When I asked her about it, she said that he had given her an ultimatum. Something like “the baby and me or else the baby and the career but not all three”. I never understood why exactly, but perhaps Dad felt threatened by her remarkable talent and didn’t like the attention she was getting from record labels at the time. My mother was beguiling and a force of nature and maybe it was all too much for him. I suppose I could ask him about it again, but I don’t want to. Kate is not around to hear his answer, and anything he says may be the truth as he sees it but will not be the whole story.

My parents separated anyway, only months after my birth, and my mother carried me and my brother back to her native Montreal. Decades later, I had to navigate a bad divorce myself, and found that being able to explain or express in an exact way how things go wrong is impossible. Their marriage, like mine, was rocky, and now I understand, better than when I was a teenager, why I almost wasn’t born.

I lived mainly with my mother as a child, but later my parents decided that I would go live with my dad in New York for my freshman year of high school. Not so much because I wasn’t getting along with Mum, they said, but more because Loudon wanted to try parenting me. I was excited but nervous, too; my dad and I had never lived together. Later, he would call that year a disaster. I would call it being a 14-year-old girl.

My dad’s work comes first. Nothing else matters to him as much – not his partners, not his children. I knew this back then, and I know it now. The year I spent with Loudon involved lots of fights and lots of silences. I learned to lie, and I imagined my dad lied, too.

We lived in an apartment on Twenty-First St, and I attended Friends Seminary school five blocks south, on Sixteenth at Third. In contrast to my all-girls’ school in Montreal, Friends Seminary was co-ed, and more liberal and artsy than I was used to.

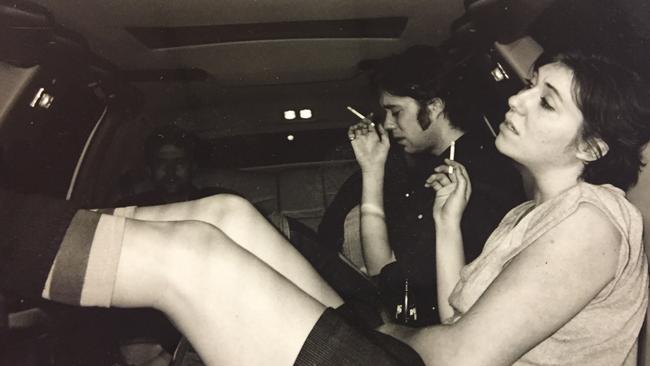

I convinced myself it was also attendance optional. Like any proper 14 year old, I hated myself. And why not? I was out of my league with these Manhattan kids. I couldn’t even spell the word Manhattan. Despite being a little less mature than some of my classmates, I quickly learned the ropes. Not with sex – I had no confidence in that department and was a little bit of a prude – but I was soon hanging out with the older kids. I think I was entertaining to them. I started school an angry kid and came out a year later a street-smart teenager.

My new best friend was a girl named Marissa. She was a year older than me and she was both very beautiful and stunningly miserable. Under her influence, I gave up clownish outfits in favour of whatever Marissa wore. Long Indian skirts that hugged her small waist and hourglass hips and turtlenecks that fit tight to her beautiful large breasts. Not quite as effective on me, or so I felt.

I listened a lot to my dad’s music, trying to find him. To get to know him. I was a big fan of his songs, and often when I was alone, I would play his records on repeat. I had learned to do this because my mother did it, too. She had all his records and had been the one to first play them for me.

She was very moved by some of his songs, and by his voice, and I felt proud of him, too. I would bend my ear searching for mentions of me in the lyrics, along with references to my mother and brother. His songs felt like proof that I existed.

That I was here. That I was real. That I had been born. It felt sometimes as if I were singing them, as if they were my story too. But they were not my story, and there were a few times I was deeply disappointed and hurt by his songwriting.

My dad wrote a couple of songs about the year the two of us spent together. One of them, “Hitting You”, starts with lyrics about how he once hit me in the back seat of the car when Rufus and I were little. Then it moves on to how he wants to hit me again but stops himself:

Long ago I hit you

We were in the car, you were crazy in the back seat

It had gone too far

And I pulled the auto over and hit you with all my might

I knew right away it was too hard and I’d never make

it right …

These days things are awful between me and you

All we do is argue like two people who are through

I blame you, your school, your mother, and MTV

Last night I almost hit you

That blame belongs to me

The other song is called “I’d Rather Be Lonely”. That one hurt more.

The year of discontent my 44-year-old father spent with his 14-year-old daughter was one he hoped to forget but that I still remember fondly. I kept my dad from what he really wanted to be doing, which was music and being by himself, which tortured him as much as anything I got up to.

But I had fun smoking pot, riding the subway at night, and meeting all these different, mostly rich, sometimes famous kids (Susan Sarandon dropped her children off at the seminary every morning) who lived in lofts in SoHo or big apartments on the Upper East Side. I had my first aching and, of course, unrequited crush that year, on a senior who lived in a brownstone in Brooklyn Heights. He was tall and good-looking and he was madly in love with Marissa. Deep down, I understood why. I was in love with her, too.

This is an edited extract from Martha Wainwright’s memoir, Stories I Might Regret Telling You (Simon & Schuster) out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout