Cochlear ear pioneer Graeme Clark’s life chronicled by Mark Worthing

Graeme Clark told his Year One teacher: ‘When I grow up I want to fix ears.’ And he did.

Bionics didn’t start in a space lab, robotics workshop or the island hideout of James Bond’s nemesis. It began in a surgical theatre at the 150-year-old Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne. And its mastermind wasn’t a weapons designer or Steve Jobs-style electronics entrepreneur. He was a softly spoken Australian doctor with a deaf father.

Graeme Clark swam against the tide in more ways than one. In a country whose best ideas too frequently end up lining the pockets of American venture capitalists, he went the opposite way. He picked up an idea he first encountered in a journal article by an American academic and turned it into a groundbreaking Australian innovation and global commercial blockbuster.

Cochlear Limited earned more than $800 million last year and employs about 2500 people worldwide. Much has been written about its core product, the cochlear implant, which was inserted into its first recipient 37 years ago.

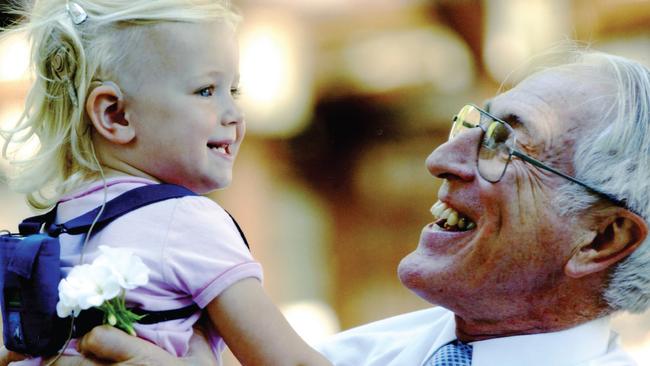

The latest tome on the subject takes a more personal approach. Graeme Clark: The Man Who Invented the Bionic Ear focuses on the device’s creator, who turns 80 this weekend.

Clark has amassed plenty of accolades through his life. He was already an accomplished ear, nose and throat surgeon when he decided to go into academic research at the age of 30 — ignoring advice that he was too old for such a detour.

Four years later he became Australia’s youngest serving professor of medicine, as inaugural head of the University of Melbourne’s newly minted department of otolaryngology.

The unexpected appointment provided Clark with a platform to pursue his dream of an electrical device that could stimulate the auditory nerves, allowing the deaf to hear.

Science historian Mark Worthing delves far back into Clark’s childhood, exploring the factors that motivated this vision and the personal attributes that helped him achieve it.

His father Colin, a popular pharmacist in what is now the outer Sydney suburb of Camden, became profoundly deaf as a young adult — as did my father.

Unlike me, Clark decided to do something about it. “When I grow up,” he told his Year One primary school teacher, “I’m going to fix ears.”

Clark also seems to have inherited his father’s compassion, a characteristic that ran in the family. Worthing describes how Clark’s great-grandfather William, a Scottish shopkeeper in the Victorian goldfields, allowed struggling miners to run up a tab even though he knew most would never repay him.

Legendary bushranger Ben Hall once held up William but rode away empty-handed after discovering that his victim was the well-known “grubstaker”.

Worthing’s account includes moments of serendipity, often in the guise of misfortune. There was the school sports injury that accelerated Clark’s career change from surgery, because throat and nose operations were becoming too hard on his neck. Then there was the suspected appendicitis that forced him off the ship taking him home from England. This necessitated a lay-off in Egypt that helped entrench the Christian faith that Worthing — himself a Lutheran theologian fascinated with the interface between science and religion — considers integral to Clark’s subsequent achievements.

Some of the serendipitous moments were less traumatic: the manuscript he read during a lunch break, by Stanford University medical professor Blair Simmons, which launched his fervour for bionics; the shell he found on a NSW beach that helped him overcome a critical engineering obstacle.

But it wasn’t all happenstance. The prominence Clark enjoys in late life masks hard times on the road to success. The long hours and tight finances of a trainee doctor, relived when he sidelined back into research. The ridicule directed at “that clown Clark” and his impossible obsession. Attempts by sceptical colleagues to discredit him. Hours spent shaking a tin for research donations. Clark and his team also faced huge technical challenges and competition from rival researchers in San Francisco, Paris and Vienna.

Even after the first implants were working successfully, difficulties and the doubts remained. The third and fourth cochlear implant operations were failures, and eventually the second device stopped working. The team had to regroup to solve a problem with leaky seals.

New challenges arose. Could the device be implanted in small children? Could it help people born deaf? The project even encountered hostility from a section of the deaf community.

Just four years after Hollywood introduced bionics to the popular imagination via The Six Million Dollar Man , Clark and his collaborators elevated the concept to real life. They achieved the first successful human cybernetic implant: the first effective interface between electronics and the human nervous system.

That’s just the beginning, of course. Teams in Sydney, Melbourne and elsewhere are labouring to do for vision and movement what Clark did for sound.

Three years ago the Bionics Institute, which emerged from Clark’s work, implanted a prototype bionic eye in a Victorian woman.

Clark himself is still working to improve his bionic ear, pursuing technology that he believes could be used to repair broken spinal cords.

Like the Six Million Dollar Man, Clark will take a lot of stopping.

John Ross is The Australian’s science writer.

Graeme Clark: The Man Who Invented the Bionic Ear

By Mark Worthing

Allen & Unwin, 240pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout