Marilyn Monroe and photographer Eve Arnold developed a friendship through the lens

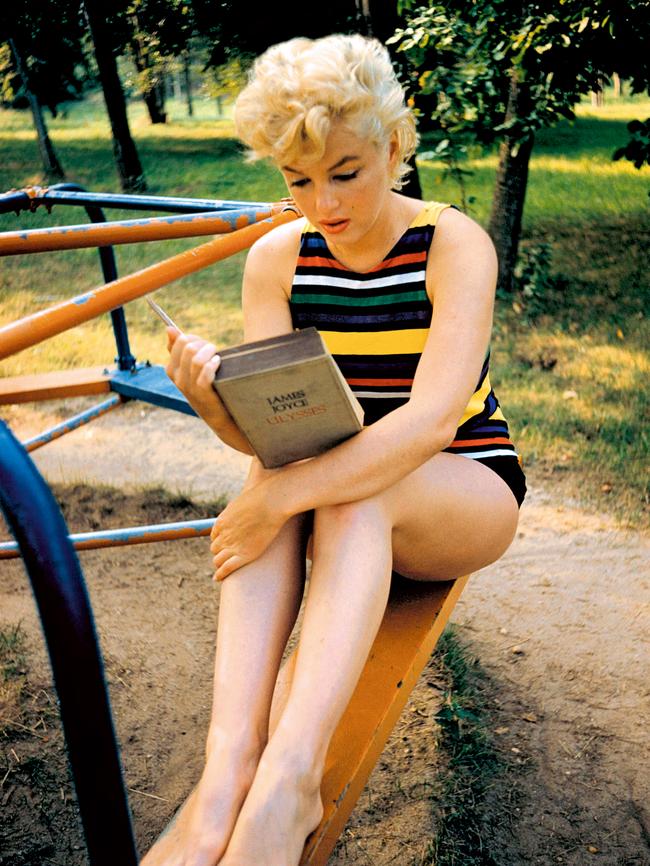

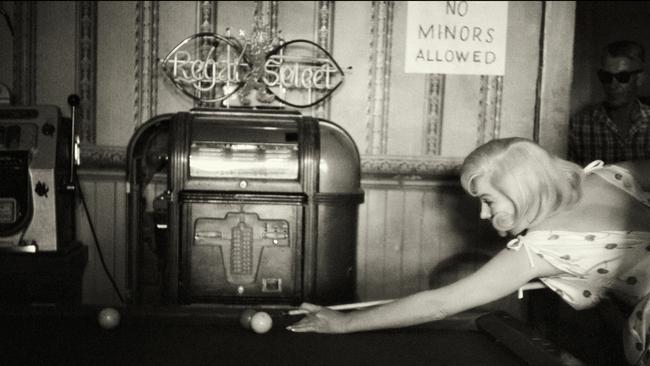

Photographer Eve Arnold spent 10 years photographing icon of the silver screen Marilyn Monroe and through the lens discovered a woman with a remarkable talent as a model ... and a friend.

In the early 1950s, Marilyn Monroe saw an article of mine in Esquire which she liked. She asked a colleague to introduce us. The pictures were of a recording session in which Marlene Dietrich sang Lili Marlene and other songs she had made famous during the war. The piece had received attention because it was documentation, a departure from the carefully lit, posed and retouched genre of movie-star studio portraits.

Since Dietrich was known to be extremely knowledgeable about, and a stickler for, proper lighting and camera work, it was considered both a coup and an innovation to have been permitted to photograph her on a bare, neon-lit soundstage while she was at work.

When we met at a party given for John Huston, Marilyn asked — with that mixture of naivete and self-promotion that was uniquely hers — “If you could do that well with Marlene, can you imagine what you can do with me?” I smiled and said I would be delighted to try and that I would talk to my editor at Esquire.

So began a professional friendship which was helpful to us both. She adored posing for the still camera, and her way of getting to stardom — and staying there — was to stay in the public eye. What better way than a picture story, which filled more column inches than text possibly could? Remember that this was the heyday of the picture magazine — pre-television.

For me she was a joy to photograph, and as her fame increased she became a source of many magazine pages, and having access to her earned me a certain cachet in editors’ eyes.

By the time we did the first pictures, she had checked out the fact that I was a member of the prestigious photographers’ cooperative Magnum Photos, which had offices in New York and Paris and agents who distributed our work worldwide. Because I owned the copyright, a story done for Esquire meant distribution abroad. She loved the idea of one photography session yielding multiple venues.

Our quid pro quo relationship, based on mutual advantage, developed into a friendship.

The bond between us was photography. She liked my pictures and was canny enough to realise that they were a fresh approach for presenting her — a looser, more intimate look than the posed studio portraits she was used to in Hollywood.

At this time she was a starlet and still relatively unknown. She had just appeared in a small part in The Asphalt Jungle, in which she was transcendent.

She was on her way up and anxious for all the press help she could garner, and she expected my pictures to get space for her in newspapers and magazines.

Over the years I found myself in the privileged position of photographing someone who I had first thought had a gift for the still camera and who turned out to have a genius for it.

Although she seemed prodigal with what she offered when we worked together and was gracious when we met, socially she always seemed to withhold something of herself, as though by giving too much away she might be misunderstood. It was hard to gauge what was beneath the surface. That kept me guessing as to how much more there was to her that she kept hidden from the camera, and it kept my interest high in her as a subject.

I photographed her six times during the decade that I knew her. The shortest session was two hours and the longest was two months, when I saw her daily during the making of the film The Misfits.

When she died, I had thousands of photographs of her. I embargoed all but the few that were in the files of the Magnum offices and those of our agents. I didn’t want to exploit the material. Because we had had the unique but complicated relationship that sometimes exists between photographer and subject, she stayed on the screen of my mind. Often when assigned to take pictures of a personality or a head of state, I couldn’t help making comparisons.

I never knew anyone who even came close to Marilyn in natural ability to use both photographer and still camera.

She was special in this, and for me there has been no one like her before or after.

She has remained the measuring rod by which I have — unconsciously — judged other subjects.

Twenty-five years after her death, I am still haunted by her as she appeared before my lens. I often go back to pictures of her to try to understand why.

By seeing her through photographs— the only way most people ever saw her — it may be possible to get some idea of how she saw herself and perhaps to glean some insight into the phenomenon that was Marilyn Monroe.

There is yet another reason for this book. One day Marilyn spoke to me of the Dietrich story that had brought us together. The headline read: “Marlene ... an Appreciation.” Suddenly she was shy and stammered: “Do you think someday you could do an appreciation of me?” Yes, Marilyn.

This is an edited extract from Marilyn Monroe by Eve Arnold and published by ACC Art Books.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout