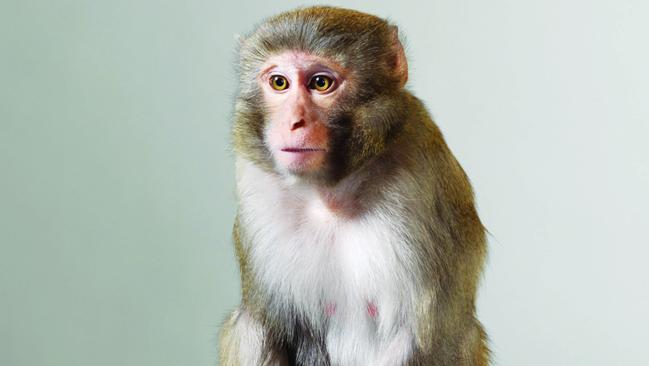

Many animals suffered before John P. Gluck found enlightenment

A scientist’s shift from animal research to bioethics was painful and enlightening.

In the middle years of his life’s journey, John P. Gluck found himself in a dark forest where the straight path was lost. Monkeys were his business, or more correctly the tools of his trade. For 20 untrammelled years he caged them, drugged them, shocked them and starved them, subjected them to crude surgeries and visited on them cruel privations. He did this largely because he could.

There were other reasons, of course. So much shared DNA suggested profound benefits for the naked ape. And Gluck, as a psychologist specialising in primate research, had questions he believed demanded answers.

What becomes of a baby rhesus monkey, ripped screeching from its mother’s arms only days after birth and confined for nine months in utter isolation? How will its cognitive functions hold up? Will its social skills take a hit? Will it cope? Only one way to find out (common sense counting for little in a laboratory setting).

Will a cannulated chimpanzee, offered free access to amphetamines and cocaine, favour one over the other? Will it favour both in equal measure? Given nothing better to do with its days, how quickly will it succumb to addiction, and at what cost? On a more practical note, how to stop the chimp from tearing the tubing from its jugular vein? Simple: keep it in a plastic helmet for the duration of the enterprise, maybe weeks, maybe months. The helmet won’t stop tract infections but it will reduce them some.

Gluck was the author and/or executor of these and other frightful experiments. When not occupied thus, he was green-lighting more of the same on his students’ behalf.

That the subjects of these grim studies led “stunted lives of boredom punctuated by episodes of fear and pain” was a fact he would not allow himself to consider. Science trumped sentiment. Suffering monkeys mattered not when suffering humanity stood to gain.

Certainly, Gluck’s own circumstances soared from one lofty plateau to the next. He graduated in the late 1960s from Texas Tech University and continued his studies with financial support at the University of Wisconsin, the “elite capital” of primate research. Within a decade he was heading up his own primate laboratory at the University of New Mexico.

Academe as he experienced it was a clubbish, quarantined world. Tenure came quickly, peer approval felt like a gentleman’s entitlement, grants and honorariums were plentiful and generous. Gluck was an undergraduate, then a bachelor and a master, soon enough a doctor, an assistant professor and a full professor. Blue skies stretched from one glorious horizon to the other and nobody talked in any meaningful way about the monkeys’ plight.

But then Peter Singer took aim at Gluck’s earliest mentor, Harry Harlow. The Australian philosopher was a minnow when he published Animal Liberation in 1975, while Harlow was a giant in his field. Tellingly, it was a few years before the book came to Gluck’s attention, and his reflex response was dismissive. Even so, he conceded that Singer’s charges were accurate and in some cases understated.

Slowly, very slowly, the clouds began to gather. A much-admired student appeared at Gluck’s door one day to announce he could no longer shock the monkeys. Another prized student, the first to receive his master’s degree under Gluck’s guidance, dedicated his thesis not to Gluck but to “the memory of G-44”, a rhesus that had died for the cause. In 1978, persons unknown broke into Gluck’s laboratory in Albuquerque and let the occupants loose. Lest their intentions be misunderstood, they chalked a blunt message on the concrete floor: “Listen Torturer: Monkeys Deserve Freedom.”

If the qualms of vigilantes and no-account philosophers were easily diminished, the indifference of his peers was not. Returning to New Mexico from a postdoctoral clinical fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle, Gluck began to question the value of his work.

As he writes in Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals, he found himself “chastened by the fact that during the entirety of my extensive fellowship I had never once heard a single reference to animal study”.

Inspecting the famous chimpanzee facility at Holloman Air Force Base with campus veterinarian S. Bret Snyder, Gluck was appalled by what he saw. The chimps’ housing recalled “a dark, maximum-security prison”, and the inmates were crazed and violent, spitting and hurling faeces as the men approached. These apes had long finished their service to NASA and were now hired out on a freelance basis to whichever laboratory had a use for them. Gluck and Snyder swapped troubled glances but it was some days before they dared speak of the matter. “The sentiment was that the Holloman chimps had paid, and were paying, a hell of a price for our research on space exploration and now medical advance,” Gluck writes. “Our shared reaction became a foundation for a friendship, one in which we both felt comfortable discussing animal issues openly.”

There was no single moment of epiphany but an exchange with Snyder gave Gluck serious pause. The New Mexico rhesus monkeys were refusing to engage in a series of memory tests. Gluck starved them to 90 per cent of their natural feeding weight, hoping to make them more responsive to food stimuli, but still the monkeys wouldn’t play. Before starving them further, he sought advice from Snyder, who suggested appetite might not be the problem.

“What does it mean,” Snyder asked him,

that your test does not engage the interest and capabilities of the monkeys? If you have to take a monkey to an extreme level of hunger where it will do anything to get some food, in the end are you still working with a monkey, or have you functionally reduced it to something more primitive, having then defeated the reason that you are using monkeys in the first place?

This was a philosophical question posed by a man of science, and Gluck took it “as a kind of intellectual gift”. Without quite realising why, Gluck found himself spending less and less time in his own laboratory. Singer’s book was reaching a wider audience and having the desired effect, notably when congress tightened the Animal Welfare Act in 1985.

The heart of Gluck’s book describes his shift from primate research to bioethics, his emergence from the dark forest where the straight path was lost. Like Dante’s, his own story must have been painful to tell. Emotional callouses were not easily chafed away and professional pride not easily surrendered.

Gluck’s career shift came at a great cost. The respect of his peers, perhaps now lost, had meant the world to him. They didn’t read his scientific papers, or not nearly as closely as he’d once believed, and they might ignore his book.

Even so, there’s plenty here for the layman. While Gluck remains a scientist at heart and a master of its cold prose, he writes here like a real writer. His preface and epilogue, describing the euthanising of three stump-tailed macaques, and a passage in the book’s guts describing the week-long “sacrificing” of about 20 rhesus monkeys, are rendered without a sniff of mawkishness. At his best, his thoughtful style and patient working of difficult ideas recall the writing of great nature essayist Edward Hoagland.

David Brearley is a Sydney-based writer.

Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals: A Primate Scientist’s Ethical Journey

By John P. Gluck

University of Chicago Press, 360pp, $59.99 (HB)