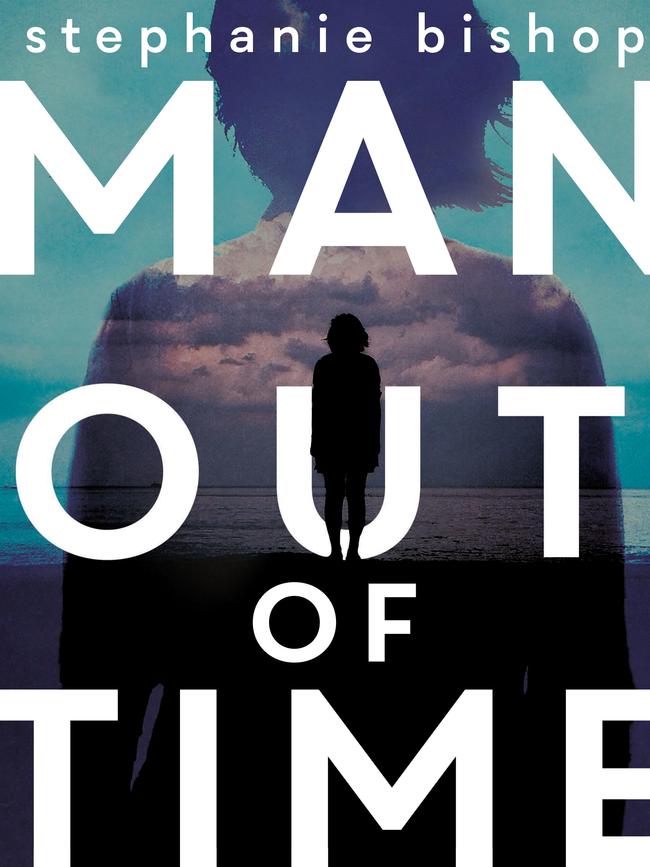

Man Out of Time; Stephanie Bishop; inexorable slide into madness

The shadow hovering over this family triangle is the father’s psychological disrepair.

All narratives are structures designed, in part, to keep the storm of reality from flooding in and ruining the carpet. Those stories we tell about ourselves and the world may be many things, but all of them work to guard beleaguered sanity. This is because they have the effect of forcing an unruly universe — one in which time inexorably flows from past to future, through what Proust called the “incurable imperfection in the very essence of the present moment”, and where events may be interpreted in as many different ways as there are observers to witness them — into some saving order, some semblance of authoritative record.

Beginning, middle, end: this is the soothing account we place, like a trailer load of witches’ hats, to advance or arrest the endless highway traffic of existence.

When we retrospectively apply these A to Z overlays to outer life, we call the resulting narratives history, or biography. But when we attempt to organise the inner stories of women and men, we have entered the realm of the speculative, and this is the domain of fiction.

Stephanie Bishop’s third novel, Man Out of Time, is an audacious undertaking, structurally complex and written in a register that combines unadorned domestic drama with elements of the fantastic. Its language is luminous and gritty and utterly determined in its task of driving the novel’s small cast to their suburban Calvary. If her last work of fiction, 2016’s The Other Side of the World, was characterised by a grave and regular formality, this new book is driven swiftly, riotously, by demons.

Most importantly, it is a work centrally concerned with a figure whose madness is expressed by the stripping away of chronological consolations. His personal teleology has been blasted by trauma and some deep psychological glitch into a thousand fragments. Living moments, memories or hopes can hold an unbearable lightness for him, floating off and dissolving in the afternoon sun. At other times, they can coalesce and harden, forming an anvil on which his remnant sanity is hammered and annealed. Past and future work upon him with such countervailing force that coherent selfhood begins to buckle and warp in the present.

The story toggles mainly between two historical points and two perspectives. Framing chapters take place in the early 2000s, describing the response of a young woman to the news of the disappearance and likely death of her estranged father. The lion’s share of the book, however, is given over to an account of the slow dissolution of a marriage during the 1980s and early 1990s, in a leafy if geographically indistinct dormitory town on the outskirts of Sydney.

Leon and Frances are (or were, we never meet them in the full health and happiness of their early life) paid-up members of the well-educated, well-heeled Australian bourgeois. They are unsnobbish and mildly bohemian, quoting Russian novelists and cultivating obsolete skills, such as knitting or threading buttons.

As a couple, they revolve more around their daughter, Stella — a precocious, watchful, charmingly feral child with a decent dash of original sin — than they do each other. Because Frances is the mother — the default parent — her love for Stella is steady and deep, yet shaded by ambivalence. Stella’s birth was an event of such terrible pain and physical damage that it seems as much a wounding as a blessing that her daughter is the result. Leon, by contrast, adores Stella with the immoderate love of a father who is already, in the opening pages, on the edge of breakdown. He is the “fun” one: cavalier, adventurous, in-the-moment and wholly engaged with the absurd whimsy of childhood in a way that his more responsible spouse could never be.

The shadow hovering over this triangle is Leon’s psychological disrepair. Rumours scattered about the text speak of a dark family inheritance. Leon’s father was a man who fell into disarray — as was Leon’s brother, who committed suicide soon before the novel opens. Frances is evidently a loving and patient woman, but when, in the wake of a disastrously failed ninth birthday, Leon takes Stella on a spontaneous road-trip and crashes the car, she is forced to accept that the man she knew, or thought she knew, has started slipping away. When we enter his head, we discover that he feels much the same:

It wouldn’t take long, once he was in the ground. It was almost a relief to think of this, if not quite a pleasure: a thought that made him feel lighter. It was the idea of transformation, effortless and unwilled transformation; the knowledge that he would one day disappear.

The challenge Bishop faces in describing Leon’s decline in the coming years, his determined edging towards the only true conclusion available to him, is that she must retain some control over the shape of the narrative, while honouring and replicating in stylistic terms his complete lack of the same essential quality.

Think of Septimus Smith in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, or Heather from Anna Spargo-Ryan’s The Paper House: characters whose descent into madness permits them access to truths or states of tenderness, or elation, or terror, that the sane world only dimly intuits.

By pitching point of view to Stella at critical points in the narrative — as a loving, trusting, child daughter, and then again as a rebellious, damaged teenager — the novel divides readers’ allegiances. Yes, Leon deserves our utmost sympathy in his psychological decline. And we trust absolutely that his love for his daughter never falters. Yet we also know Stella’s father is a dangerous man, to himself and others; that he is increasingly unable to tell the difference between his fantasies and the reality where his wife and daughter dwell. The degree to which Leon’s love is transformed by madness into something darker and more intense is the fulcrum that lifts the novel out of analytic case study and into a broader human drama. It asks: what should the daughter of a mad father expect to inherit?

Man Out of Time is a considerable accomplishment in its own right, and a marked advance in ambition and sensibility from Bishop’s earlier work. Though it is occasionally marred by a too-close identification of authorial intelligence with Leon’s interior states — the anchor of story is sometimes dragged along the bottom by the sheer force of his insanity — at its best the novel questions our fealty to the reality we have jerry-built to protect us from what Leon suffers. Even Frances, as the sane half of the couple, appalled by her husband’s malady, comes to question the value of “normalcy”:

She had taken herself to be the measure of the family, the temperate, steady core. But this too might be in error, an indulgence of a different kind — the belief in her own significance, her centrality.

Or, as psychoanalyst Adam Philips puts it:

Sanity, as the project of keeping ourselves recognisably human, therefore has to limit the range of human experience. To keep faith with recognition we have to stay recognisable.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Man Out of Time

By Stephanie Bishop

Hachette, 293pp, $29.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout