Malcolm Turnbull laid bare in Paddy Manning’s Born to Rule

Malcolm Turnbull’s high opinion of himself has turned people off since his school days.

The past seven years have been an incredible saga of political instability featuring three prime ministers of extraordinary incompetence. Kevin Rudd was a narcissist driven by such a sense of vengeance that he made Jacobean revenge plays seem tame. Julia Gillard, tired of being Rudd’s understudy, wrenched power from him only to suffer a case of terminal stage fright. And Tony Abbott, instead of maturing in his role as prime minister, regressed. His vocabulary became more childish, with its talk of goodies and baddies, and all of this was underpinned by a Manichean view of the world.

No wonder Malcolm Turnbull came as a relief. At his first appearance as Prime Minister he immediately brought a sense of calmness and rationality to our political landscape. Yet his ascension to the leadership of the Liberal Party was not a surprise to anyone who has been even vaguely interested in Australian politics. Since he was a teenager he made no secret of his desire to become prime minister. Not for nothing is Paddy Manning’s biography of Turnbull titled Born to Rule.

Yet Turnbull’s beginnings, as Manning describes well, were inauspicious. His mother, Carol Lansbury, was an actress and radio dramatist who married her godfather, who was 40 years older. Her husband was to die six months after the wedding and she soon hooked up with Bruce Turnbull, a Bondi lifesaver, sportsman and budding hotel broker. Their son was born in 1954 and was a handful, or as his mother said, ‘‘a bundle of demonic energy’’. The marriage was unhappy and when Malcolm was nine, Carol took up with an academic and followed him to New Zealand, not before taking all the furniture and even the cat.

Malcolm lived with his father in dreary flats surrounded by pensioners and elderly widows. Later he was sent to Sydney Grammar as a boarder. He had few friends and seemed almost like an orphan. He was intelligent, a brilliant debater, a narcissist of the higher order, arrogant and disliked by his fellow students. There was little that was boyish about him and many people, including his principal, thought he was ‘‘born middle-aged’’.

Manning offers many examples of Turnbull’s condescending attitudes and yet it’s tempting to speculate that his incredible self-belief was rooted in his early awareness that he could depend on no one but himself to survive and prosper. It’s no wonder he has always found it hard to be a team player and that, since his school days, a common criticism is that everything he’s done has been to be to advance his own cause.

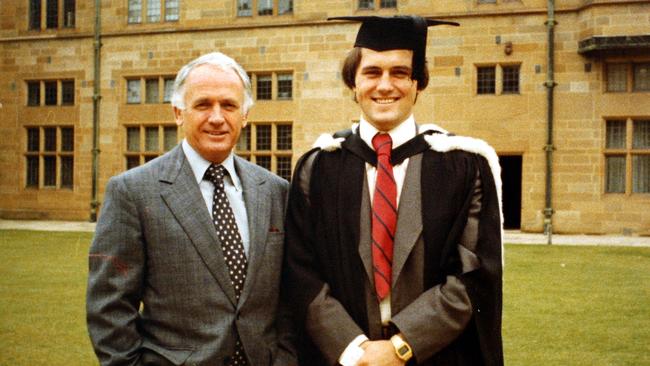

He studied law at Sydney University but focused on journalism in his early 20s, writing for The Bulletin. Although he thought highly of himself as a journalist (as he did of everything he attempted) the prose style was pompous — though he was always good for a controversy.

Turnbull’s close friends were quintessential Labor men such as Neville Wran and Bob Carr. He made it clear to them and others that he wanted to be prime minister by 40. The Labor Party wooed him for years, but in 1981 he ran for preselection as a Liberal candidate and failed, so he turned his attention to law.

He may have been rising in the world but there was a Jekyll and Hyde quality to him. He could be charming but also had a terrifying capacity for rage, kicking down doors and savagely abusing people. It comes as no surprise that one nickname was ‘‘the Ayatollah’’.

Manning makes it clear just how much the death of Turnbull’s father in a plane crash devastated him, but it also made him financially independent because his father had died a multi-millionaire. He never had to worry about money again, but he craved fame and success. This came at the age of 29 when he defended Kerry Packer against baseless allegations in a royal commission that the media baron was linked to an unsolved murder, drug importation and tax fraud.

After that he became known throughout Australia for the Spycatcher affair. He defended Peter Wright, a former M15 agent who wrote a book alleging Roger Hollis, the head of Britain’s domestic counterintelligence between 1956 and 1965, had been a Soviet spy. Spycatcher was to be published in Australia but the British government sought to stop this, citing security concerns. Margaret Thatcher’s government was represented by inept and condescending English toffs who underestimated the colonial Turnbull.

They even went as far as tapping his phone. But the media-savvy and cocksure Turnbull won a celebrated victory and, as he was to say, ‘‘I have always been a republican, but the Spycatcher affair radicalised me.’’

Turnbull may have wanted to enter politics but he was more focused on becoming wealthy. He started a cleaning business with Wran and became a merchant banker. He may have earned a fortune but Manning details many a failure along the way. Even so his bad habits hadn’t changed: he’s accused of never giving credit where it was due, being ungracious towards those who helped him, litigious to a pathological degree, and having little empathy for those less fortunate. One of his worst traits was that under pressure he lashed out at those around him, especially his inferiors.

He once said, ‘‘There may be an unattractive side to my personality, but I do not like losing. I live to win.’’ The trouble was that he didn’t realise the public thought he was rich, elitist and patronising. He may have had his money and heart behind the republican cause, but there’s no doubt his ubiquitous presence in the 1999 referendum was a factor in its defeat.

His progressive views made him an ideal Labor candidate, but he believed there were those in the party who would block any chance he had of becoming PM because he was rich, so he joined the Liberals and, after spending a fortune on his campaign, became the member for the Sydney seat of Wentworth.

He arrived late in politics and was in a rush to realise his ambition. He was obnoxious and Machiavellian in his dealings with the leader of the opposition, Brendan Nelson, and overthrew him in 2008.

It wasn’t long before he made a fool of himself. A strange Treasury official, Godwin Grech, convinced Turnbull that Rudd and Wayne Swan had made shady deals with car dealers. The proof turned out to be a fake email. His eagerness to gain power, his refusal to listen to others, and his arrogance and inability to read human beings had brought him undone.

He retired to the backbenches but this fiasco was the making of him. He reinvented himself, lost a lot of weight, became a Catholic and, according to his wife Lucy, began to calm down.

He made sure he was the one sensible politician in both parties to try to rein in the moral panic about Bill Henson’s photographs being the work of a pedophile. It was an act of courage at a time when media shock-jocks and cowardly politicians revelled in their philistine attitudes.

Yet, as Manning describes in forensic detail, Turnbull’s five years overseeing the NBN were a disaster. It was slow, hideously expensive and obsolete. Despite this he still had dreams of becoming PM and this time, with uncharacteristic patience, he stalked the bumbling Abbott and achieved his goal late this year.

Manning began his biography in February and finished it in October. The rush shows. Sometimes there is such a flurry of details about Turnbull’s projects that he disappears for pages on end, and the story is disfigured, almost on every page, by the unsightly acne of cliches (people tear their hair out, they have a whale of a time and are soon back on the horse, hitting the ground running, until the cows come home, when they’re not coming apart at the seams or changing their spots).

Manning makes it clear the difficulties a progressive such as Turnbull has ahead of him, not so much with the public or opposition but the conservative agenda Abbott bequeathed him. So for now he has to stay harsh on border protection, leave climate change policy as it is, oppose a free vote on marriage equality and avoid the republican debate.

Manning doesn’t speculate too much on Turnbull’s psychology, but believes he has mellowed and learned from his failures. Yet if Turnbull has to fear anyone, it is himself. Despite hints of a new-found humility, the spectre of hubris still haunts him.

Louis Nowra is a novelist, playwright and screenwriter.

Born to Rule: The Unauthorised Biography of Malcolm Turnbull

By Paddy Manning

MUP, 442pp, $45 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout