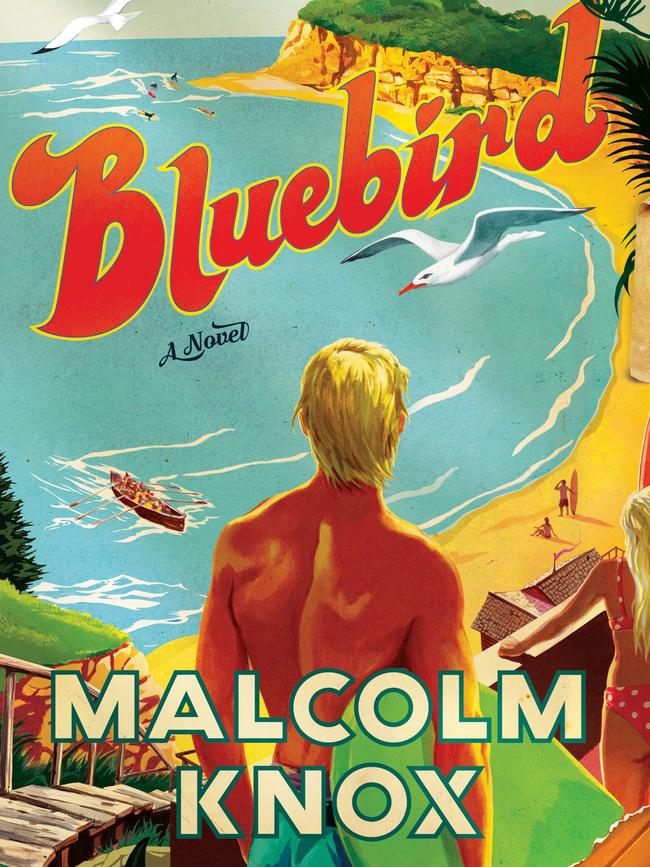

Malcolm Knox makes ‘good trouble’ with new novel Bluebird

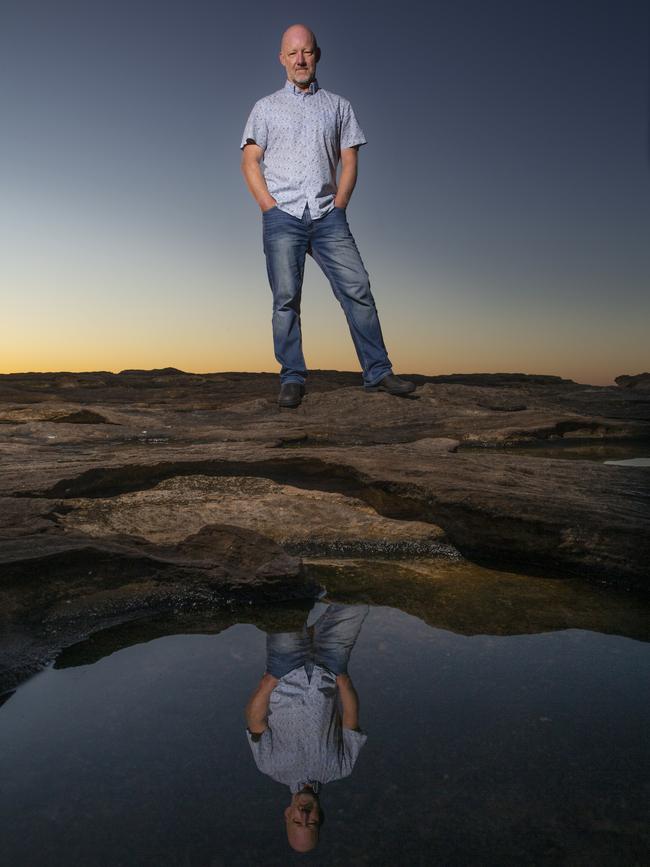

Malcolm Knox turns his attention to the aspects of Australian culture that require a product recall.

The very first review I wrote – in late 2000, somewhere between Y2K’s flubbed apocalypse and the authentic disaster of 9/11 – was of Malcolm Knox’s debut novel Summerland.

Back then, the default mood among a new generation of Australian writers was low, grungy introspection. Economic precarity, drugs, transgressive sex, dirty realism and postmodern experiment: these were the subjects and stylistic approaches of the moment.

Summerland was different. It was formal, mannered, subtly metafictional. It dealt with bourgeois mores and toxic masculinity – with the destructive freedoms offered by privilege and wealth. The novel’s tone was plaintive in a young writer’s way, nostalgic for some lost antipodean Eden which never existed in reality. But the authorial eye was laser-focused on the underlying social and economic conditions on which this nation’s stubbornly durable class system was built.

It helped in this regard that Sydney-based Knox was a journalist first. A reporter’s nose for sensation shaped his imagined narrative, while a cool, sociological rigour underwrote the fiction’s concerns. The result was an elegant riff on Ford Madox Ford’s novel The Good Soldier, set mainly on the paradisal coastal fringe of Sydney’s northern beaches.

Two decades and five novels later, Bluebird sees Knox return to that same ground, this time on an ambitious scale and from a mature perspective.

The story he tells is funnier, looser-limbed – the work of a writer comfortable in his skin and in full command of his material – but the sense of sadness and loss is not strained for this time around. His is a true, deep and ultimately scarifying vision of what Australia has gained and lost in the interim.

Bluebird is the name of a concocted beach suburb, north of a metropolis called Ocean City. Yet it adjoins real Sydney suburbs: the surf clubs of Manly and Bondi Beach come to compete in its beachside carnivals. The same issues – of council amalgamation, cookie-cutter dwellings made of concrete and glass, real estate owned by city money or offshore Chinese crowding out the locals, obliterating the parochial flavour that first drew outsiders in – still obtain.

At the heart of this gussied up village, a neoliberal fantasy of the Good Life, lies an architectural sore thumb known as The Lodge. A hymn to bad taste, slapdash and tumbledown, The Lodge occupies a dress circle position in the otherwise impeccable, moneyed beachside suburb. Everyone knows it; only the few remaining old-school Bluebirders love it. And no one more so than its current occupant, Gordon Grimes.

Gordo, as he is universally known, runs the lodge as an unofficial drop-in centre for the area’s depleted cohort of locals. They’re the people he went to school with: fellow surfers, midlife burnouts, part-time drug dealers, the congenitally unemployed who live out of vans or bunk down with elderly parents – scuttled crabs washed ashore by the wave of affluence that remade Bluebird during their adult years.

But Gordo’s attachment to The Lodge goes deeper than nostalgia. For reasons that are doled out with careful economy as the narrative progresses, we learn that his desire to hold onto the old place has become an obsession: one that, at the novel’s outset, has cost Gordo his marriage and relationship with his son.

Complicated questions of ownership and inheritance surround The Lodge. It does not wholly belong to Gordo: he was gifted a third share in the house by his ex-mother-in-law Leonie, a woman whose offstage machinations remain obscure yet reliably malicious, especially since she also granted a share of the property to Gordo’s estranged wife Kelly, a stepdaughter whom she has always despised.

Leonie’s abstract greed is what provides the backing for Gordo, his family and friends, to respond to in more full-fleshed ways to the potential for its loss.

On one hand, then, Bluebird offers up a story of marriage and property, a traditional subject of Anglosphere fiction from Jane Austen to Henry James. Yet the novel’s other strand is more meaningful and urgently felt. It explores those human impulses that cannot be weighed on the all-purpose scales of economic rationalism: connection to place; the means by which the past survives in us, whether through trauma, inherited ideology or generational bonds; and how these first two forces shape our present relationships, whether to loved ones, friends or neighbours, and passes on to our children.

Gordo emerges from this sifting of intangibles as a Quixotic figure. He has made a vow to The Lodge for reasons that are powerfully private. It makes him an anachronism; it renders his vigil over the house absurd.

But in a story where an older generation of Bluebirders, ‘‘square-jawed and heavy-browed’’ mid-century avatars of Australian masculinity, are revealed as predators or crooks, and where the generation below them are superannuated early by market forces, or damaged by epidemics of drugs and suicide – where even those who achieve some version of success do so by selling their own village to the highest bidders – any truly moral gesture will seem absurd. Knox is too intelligent a writer to make a hero of Gordon Grimes; he cannot win the battle against forces so omnipresent yet diffuse, only force a momentary draw.

What he does instead is array the man’s stubbornness against a society that, despite being dangerously worn, proceeds as if the national virtues Bluebird supposedly embodied – mateship, a sense shared sacrifice and the fabled fair go – remain sound.

Bluebird reminds us that the purpose of fiction is to argue, intermittently, that aspects of a culture may require a product recall. It might be said, by extension, that the role of the novelist is similarly Quixotic: that the telling of such stories is a doomed enterprise, that the levers of power and the pure force of economic orthodoxy remain untouched, even by the most savage satire or insightful critique, after all.

But this is to ascribe a theological certainty to some stories we tell – about the role of the market, say, or the strict parameters of our current political compact – while suggesting others are simply made up.

Bluebird’s panoptic vision of Australian society, its questioning of the myths that undergird our self-conception – its success in embedding broader appraisal within a believable, local, domestic narrative frame – presents another possibility.

By giving us a drama of conscience, the novel offers readers a series of alternate ethical possibilities. It uses verisimilitude to persuade us, just as a politician’s speech employs rhetoric to do the same.

Knox’s literary career reminds us that language, in the right hands, can be dangerous. It can render stories that convince us our potential for transformation – as individuals, as a society – remains alive.

It has been one of the perks of the job to watch Knox grow into his talent, but it has been an honour to witness him make the kind of ‘‘good trouble’’ which is the true artist’s right and obligation.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian. Bluebird by Malcolm Knox (Allen & Unwin, 496pp, $32.99).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout