Master of subtlety

Mahershala Ali might be an award-winning supporting actor but he shows he is born to lead in new film Green Book.

Mahershala Ali has one acting goal above all: “I’m always trying to do less.” No matter how small or large the role, whether he plays a medical examiner or a crime kingpin, a political lobbyist or a cop, he’s always after subtlety, always looking to pare back, to reduce, to avoid the merest hint of histrionics.

In his new film, Green Book — for which he has just won a Golden Globe for best supporting actor — restraint is explicitly built into the character. The movie is based on a true story, about a journey two men took through the American south in 1962. It could be described as a flipped version of Driving Miss Daisy. The chauffeur is a tough-talking Italian-American guy; sitting in the back seat is an elegant African-American musician, a classically trained pianist.

Ali’s character, Don Shirley — also known as Dr Shirley — is a fastidious, cultivated, dapper man. Set against him is Viggo Mortensen, playing a former bouncer called Tony Lip, a loud, bulky, assertive figure, hired to drive and look after Shirley as he and his musical trio tour the segregated south.

Why did Don Shirley choose to go on this journey? He would be feted on stage, then shunted into second-class hotels, refused service, humiliated or, with grim, unsettling regularity, be threatened or endangered.

For Ali, the point was that Shirley understood the deal. “He was putting himself in the fray,” is how he describes it. “I think he volunteered in a way that made sense to him for his talent and his offering, his gifts. For him to go down to the south, a place rampant with old stereotypes of people of colour, specifically black people at the time — I think it was really important to him to expose himself to that community and allow them to see and have an experience of a black man who had so much education and talent. Because at the time people didn’t believe we had the capacity to be educated and we weren’t believed to be intelligent.”

Shirley’s driver got his nickname because he was a loudmouth. The film shows his casual racism: when two black workers come to the house and Tony’s wife gives them a drink of water, Tony later throws the glass away. This attitude simply falls away, the film suggests, in the course of the journey.

Tony Lip is in many ways the teller of this tale, the original author of the account; the movie comes to us via Nick Vallelonga, his son, an actor, writer and director who co-wrote the Green Book screenplay, basing it on his father’s recollections. He also appears in the film, and there are family members in cameo roles.

Ali didn’t have the same access to detail and support as Mortensen did, playing Tony Lip: he had less to go on, more to conjure up for himself. Since the film came out, Shirley relatives — who were not contacted before the making of the film — have taken issue with some of the details of Green Book’s characterisation. Ali’s response has always focused on the importance that he sees in putting the figure of Shirley on screen.

Yet there were things about the character that he felt he needed to add, things he was absolutely certain about. When director Peter Farrelly got the cast together before the shoot, Ali recalls, he asked them to read through the script and share ideas. Ali had some suggestions. There was a scene in which Tony Lip expresses his admiration for Shirley as a popular performer and pooh-poohs the notion of his playing classical music. Shirley was an accomplished musician but had been discouraged from pursuing a career as a purely classical pianist: he said he had been told American audiences were not ready to accept him.

This scene contains a moment that has value, Ali says. “It’s Tony saying, what you are is beautiful and amazing and unique. It is something to appreciate that he recognises that. But the scene can’t end there. It needed more. It has to end with Doc Shirley saying, ‘I wanted to be something else, though. I have the ability to be something else.’ ”

Without that acknowledgment, Ali says, “the movie goes on and the story wraps up, and that is something that was never properly addressed”. Spectators need to be aware “of his passion and aspiration for an experience he’s not able to have because of his race. So I felt like it was really important that the audience didn’t walk away feeling that it was OK that Don Shirley never got to do that. And so we have to find those moments for it not to be so clean and easy.”

Farrelly, he adds, “was open to that, he never fought it. If anything, he wanted to welcome that kind of conversation and discourse.” So Don Shirley doesn’t just say: “Thank you, Tony.” He adds: “But everyone can’t play Chopin. Not like I can.”

Green Book sets out to show us, perhaps a little too easily, that we can all get along, that Tony Lip and Don Shirley can appreciate each other and become friends. Yet there are other encounters in the film that also matter to Ali.

There’s a scene in which the car stops by the roadside and draws up alongside a group of black sharecroppers working in the fields nearby. Don Shirley looks at them and they look back. What Shirley sees, Ali says, is a situation he’s aware of: he’s not a naive or unworldly man. But knowing and seeing are different things, he says. “Nobody’s up there farming and sharecropping in Harlem, in New York City or outside of Carnegie Hall.”

The men looking back at him are seeing “an alien of sorts”, Ali says. “They’re looking back and seeing something that is otherworldly, they’re seeing a white guy opening a door for a black man in 1962, and a black man who not only has a car but he’s being chauffeured in that car. And not just any car; it’s the pinnacle of cars at that time, it’s a Cadillac.

“So to see all that in one moment in the context of the time, I think it’s an extraordinarily powerful scene.

“Don Shirley was the height of what you could achieve, and those people with that status in society was where the vast majority of working-class African-Americans were. There were so many black people sharecropping in that time. My father-in-law was a sharecropper; he’s in his 70s, and that’s what he was doing.”

Ali was born in 1974 in Oakland, California. His surname was Gilmore but he changed it to Ali in 2000, when he converted to Islam: his wife, Amatus Sami-Karim, whom he met while doing graduate studies, is Muslim, and an artist. His first name is Mahershalalhashbaz, a Hebrew prophetic name from the Book of Isaiah that means “hurry to the spoils”. He used it professionally until 2010, when his name was to appear on the poster for The Place Beyond the Pines and it was too long. He decided it was time to abbreviate.

Ali’s father, Phillip Gilmore, had given him an inkling of what it was like to live a creative life. His parents had married when they were young and separated early. Gilmore left when Ali was three and moved to New York to pursue his career as an actor and dancer, but he kept in contact with his son. Ali has talked about visiting his father when he was on Broadway or on tour, of watching him in Dreamgirls, of being taken to movies and plays, of seeing Jeffrey Wright and Savion Glover on stage.

He initially went to college on a basketball scholarship but gravitated towards theatre. He was also beginning to envisage a career as a rapper, calling himself Prince Ali. His first album was about to be launched just as he was accepted into New York University’s graduate acting program, and that was that for rap.

After graduation, he landed what should have been a big break, as a main character in the television series Crossing Jordan, playing a medical examiner. He left after the first season, frustrated at the lack of development. Roles in film and TV followed. His feature debut was a minor role in David Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

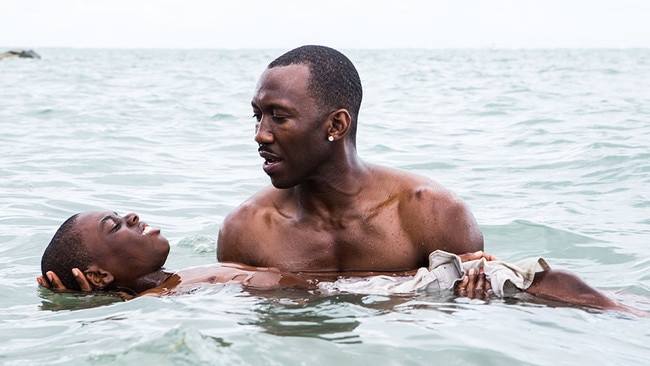

He came to wider attention in the TV series House of Cards as a suave political operator, Remy Danton. It was a significant break but it almost cost him the role in Barry Jenkins’s 2016 masterpiece, Moonlight. Jenkins knew him from House of Cards and was uncertain about considering Ali for Juan, a local drug dealer who plays a transformative role in the life of the film’s central character.

In his audio commentary for Moonlight, Jenkins talks about the way Ali captured the complexity and range of Juan. “From our first meeting he understood the duality of this character, of someone who was capable of such grace and considerateness and kindness but could also go to some very dark places.”

Moonlight is a story told in three parts. Juan is only in the first part but his presence haunts the film. It’s a supporting performance at its most crucial and remarkable. Ali won the Oscar for best supporting actor last year, and every other major award, although the Golden Globes, incomprehensibly, overlooked him. Their choice of Ali for best supporting actor this year in Green Book might represent both recognition and atonement.

In the aftermath of Moonlight and the Oscar win, Ali has become a sought-after figure, with leading roles in his grasp at last. In the TV series Luke Cage he plays Cornell “Cottonmouth” Stokes, a New York crime kingpin who runs drugs and guns but pours his emotional energy into a club, Harlem’s Paradise, that he has lovingly restored.

Brutal, suave, occasionally sentimental, Cottonmouth had musical aspirations but was forced to be part of his family’s criminal business. The show was meant to focus on Marvel superhero Luke Cage, ostensibly the central character of the series, but Cottonmouth effortlessly dominates every scene he’s in: flawed, eloquent, eye-catching.

Reflecting on his career, Ali told Rolling Stone about finding an old casting photograph of his father: young, handsome, the quintessential aspiring actor. On the back he had written: “Hey Ma. Still trying to be that leading man.” It’s a discovery that reminded him of what his father had been searching for. “In a way, it felt like I’d picked up the baton.”

He’s the co-lead in Green Book but in awards season he’s being put forward for best supporting actor, with Mortensen as contender for the best lead actor.

He also stars in season three of True Detective, which premieres on Foxtel next week. In the world of peak television, this is as highly anticipated as it gets. In True Detective, he’s at the heart of a story that stretches across decades: he plays Wayne Hays, an Arkansas police officer consumed by the disappearance of two children, a brother and sister, a mystery whose ramifications follow him throughout his life.

Originally, Ali had been offered a supporting role: Hays, a Vietnam veteran, had been envisaged as a white character. Ali pitched himself for the lead, sending writer and showrunner Nic Pizzolatto photographs of his grandfather, who had been a uniformed police officer. He told Entertainment Weekly that he was “presenting the idea of Wayne being a black cop and why it would work. [It was] a slightly tweaked vision inspired by what Nic already had on the page.”

The transitions are both striking and inevitable: Hays is sorrowful, jittery and haunted in turn. In 1980 he seems to carry sorrows and secrets buried so deep they’ve become part of his body. Ten years later, a married man with children, he’s on edge, deeply unsettled by new revelations about the case. By 2015 he’s a grey-haired widower with a fading memory, being interviewed about the investigation for a true crime TV show, struggling to reconnect with what he knows and has forgotten.

It’s a performance that once again does more with less — and it is, unquestionably, the lead.

Green Book opens on January 24. True Detective, season three, begins on January 14 on Foxtel.