Luke Williams’s The Ice Age traces journo’s plunge into crystal meth

This landmark insight into ice addiction, by a gonzo writer, unflinchingly describes society’s psychotic plague.

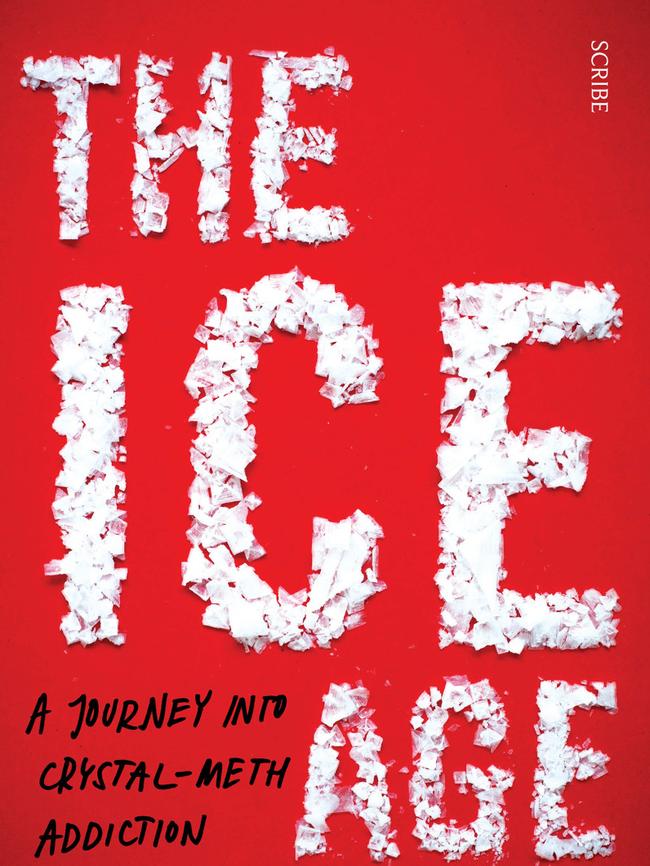

The Ice Age: A Journey into Crystal-Meth Addiction, by Luke Williams (Scribe, 367pp, $29.99)

When reading books for review, I have a habit of folding a small triangle in the corner of each page that contains a particularly memorable, funny or insightful moment. I also draw an asterisk beside the section in question, so that I can easily locate it when typing notes afterwards. By the time I got to the end of The Ice Age, the bottom right corner of the book was swollen with dog-eared page markers and the margins lined with scrawled asterisks.

It had been a while since I had defaced a book in such a manner; most titles are lucky to contain more than a handful of noteworthy moments. In sum, I folded 32 of its 367 pages. The Ice Age offers something never before attempted by an Australian author: it investigates the allure and popularity of the illicit drug crystal methamphetamine, while simultaneously charting the writer’s spiral into addiction and “full-blown psychosis” at age 34.

It began a couple of years ago, when Luke Williams came up with the idea of moving in with a “junkie and jailbird” friend in Pakenham, an outer suburb of Melbourne. Williams knew his friend dealt drugs from the house, which meant “meth use and meth users were near-constant companions”. In classic gonzo journalism style, he sought to embed himself in a subculture to report on it accurately and fully.

But after he began injecting the drug along with the revolving door of questionable characters who visited the house at all hours, the assignment slipped his mind. “I cooked my brain so badly on meth that, after a few months, I genuinely lost track of the fact I was writing a story,” Williams writes in the first chapter. “I stopped taking notes, and became fixated on a series of non-existent events with myself at the centre. So, yes — as you may have gathered — I got a story, a very good story. Only it wasn’t the one I was expecting; I didn’t bank on becoming a psychotic meth addict myself.”

Williams is a fine writer, and this is the primary appeal of The Ice Age: never before have I read such a vivid, detailed and balanced account of methamphetamine use. Many users lack the ability to articulate the effects of the drug and are unable to interrogate their own behaviour by considering how it affects others. Williams does both, and in this sense his is a landmark book. It should be studied closely by those who work in fields where meth use is prominent as well as by those who draft the policy that determines how society treats users.

It is a flawed book, however. Williams too often submerges himself in law enforcement statistics and lengthy policy reports. There are only so many times one can read about trends in police clandestine laboratory detections before eyes glaze over. These wonky discussions are rendered in dry, inert language and jar against the vibrant details that the author summons when writing about his own experiences with the drug.

This seesawing between the distant-historical and present-contemporary is my principal complaint, as it tends to arrest the narrative momentum that Williams skilfully builds. In this sense, The Ice Age can’t quite decide if it wants to be a first-person account of addiction or a worthy examination of the social, political, scientific and economic factors that led to the crystallised form of the drug becoming so popular this century.

Still, its strengths are many: the author makes careful distinctions between powdered amphetamine (speed), powdered methamphetamine (meth) and crystal methamphetamine (ice), and describes the probable factors that saw the latter version taking precedence in recent years.

Another narrative thread is the author’s analysis of the factors in his childhood and adolescence that contributed to his drug use in later years. Chief among them is the social isolation he felt after he discovered his sexuality, as this excerpt illustrates:

This was the dawn of a new era in my life — I would know now what it was like to be the lowest-ranking male. To use the metaphor of a diseased tree, the problem was that I was blossoming into an adult that some considered to be threatening to the population; an adult that needed to be cut down, turned into sawdust, and buried in a hole to ensure it didn’t spread weakness, perversion, and infection. I am, in fact, talking here about the life of a gay teenager in post-AIDS 1990s country Australia.

This led to anxiety and depression, and then the regular use of stimulants such as ecstasy and what he thought was speed but turned out to be meth. From this came the author’s first psychotic breakdown, at the age of 20 or so. It was an unpleasant outcome that prompted him to quit drugs for five years, but psychosis revisited him when he moved into the Pakenham house to begin living out this tale.

A former Triple J radio reporter and an accomplished freelance journalist — his front-page story for The Saturday Paper on his crystal meth addiction was a finalist for a Walkley Award in feature writing in 2014 — Williams has a fine eye for the details that make stories lodge themselves in the brains of readers. These details are rendered in such stark, unflinching terms that it is almost impossible to look away.

While the book could have benefited from a firmer edit, it sounds as if the publishers had their hands full with what the author delivered. “The drafts of the final chapters to this book were sent back from Scribe with the message: ‘I have never seen anything like this in all my years of editing,’ ” Williams writes 12 pages from the end. Yet the fact remains The Ice Age is a remarkable, original and compelling journey. To quote the king of gonzo journalism, Hunter S. Thompson: buy the ticket, take the ride.

Andrew McMillen is a Brisbane-based freelance journalist and author of Talking Smack: Honest Conversations About Drugs.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout