Low and high roads in Asia

Experiences in Asia have left very different memories on authors Luke Williams and Phil Brown who recount their times there.

The title of Luke Williams’s second book recalls George Orwell’s 1933 tale of poverty in two cities: Down and Out in Paris and London.

Orwell was in the muck of destitution, eking out a living elbow-deep in dirty dishwater.

Williams’s memoir is that of a traveller, an outsider writing from a position of white privilege, even as he attempts to fraternise with the locals on their terms.

Down and Out in Paradise (the name is a little ironic) tracks three years of dissolution as he chases taboos all over Asia, revelling in its excesses and his own self-destructive energies. His spin on the “Westerner traipsing over Asia” schtick is seen through a lens darkly as he courts the unsavoury (Thai monks burning baby corpses in black magic rituals, anyone?). Those expecting a middle-class romp in search of earnest affirmations in tropical climes are advised to look elsewhere; this book eschews any sanitised pampering of the soul.

There may not be much rock ’n’ roll but there is an oversupply of sex and drugs (of astonishing variety), and if that’s not hardcore enough, there are also stints in a jail cell and a psych ward.

Williams’s wanderlust was provoked by a desire to escape his circumstances and his own mental cage but redemption in this piece of long-form gonzo reportage/memoir is not easy or even inevitable.

The author has no filter, which means this memoir includes his most anti-social, ignoble behaviour (serial shoplifting, violent temper tantrums). His debut book, The Ice Age, a journey into crystal meth addiction, is a telltale precursor.

In the beginning of this one he is coming down on said substance while touching down in Kuala Lumpur.

It sets the tone for the rest of the book, a seedy mix of hedonism and self-flagellation.

His misadventures include being a sex worker in Thailand, eating the still-beating heart of a snake in Vietnam and running out of antidepressants in Indonesia, which leads him to glide “along the borderline of neurotic and psychotic”.

With a family history of mental illness, Williams’s unstable mind and uncontrollable urges accompany his trekking across several countries, occasionally interviewing people of note (including a pastor for people on death row), but more likely indulging himself in every which way.

The author has form as a travel writer but the Third World places he visits are not airbrushed and he’s given to grandstanding, generalised comments: Pattaya is “the world’s biggest brothel”; Varanasi is “an open-air hospital ward for the terminally ill (without any nurses or medical care) a big homeless camp, a slum and a holiday resort all in one”.

Williams has enough awareness to know he can be offensive (racially, sexually, morally) but the distaste is often self-directed as well and there is something gruesomely compelling in his narrative even if its druggy, sexploitative ramblings become excessive.

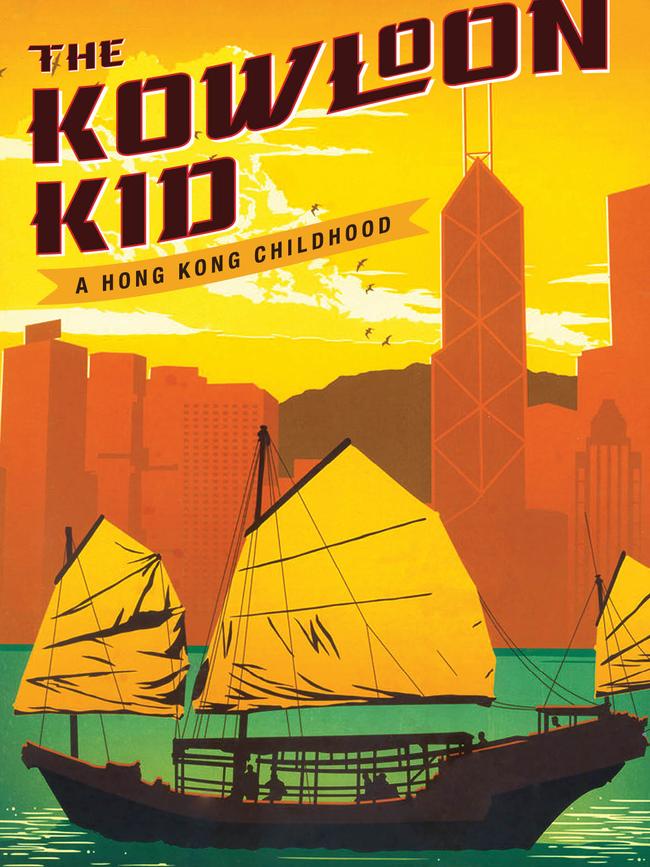

In contrast, Phil Brown’s memoir, The Kowloon Kid, is bathed in genteel, lavender hues of cocktail hour.

However, Brown also explores incursions of white (colonial) trespassers on Eastern soil. It’s a portal into the past, and begins in unashamed romantic tones, in the lobby of The Peninsular Hotel in Hong Kong, the “cathedral of my childhood”.

His book is largely a nostalgic sweep to the 1960s, where Brown and his family grew up in the Kowloon area of Hong Kong.

His father and grandfather, both civil engineers, had lucrative business dealings there, rebuilding it after World War II as well as capitalising on the need to accommodate the swelling ranks of refugees fleeing the borders of Communist China.

Brown and his siblings were uprooted from their Hunter Valley home in NSW when he was six, causing the author to confess that “his Australianness is laced with vestiges of my very British-colonial salad days”.

The life of the expat was privileged and it’s a little bit cringeworthy when Brown reminisces about the “good old dying days of that colony of Empire upon which, once upon a very good time, the sun never set”.

He talks about a time of patriarchal feudalism. He recounts having his bath drawn by the servant, “the amah”; a time when waiters were always called “boys, regardless of age” and Sikhs with shotguns guarded banks.

Now based in Queensland, Brown does not grow up to continue the family’s construction dynasty but thanks to the largesse of its labour, his childhood (seven years in Hong Kong) was gentrified luxury and the book recalls his rarefied upbringing: visiting the Kowloon Cricket Club, being spoiled like a “princeling”, going to chaotic building sites that his family ran and sharing a colonial enclave of a school with children from the British Isles, white South Africans and other caucasians.

There is little time devoted to the broader socio-economic climate of the era, including the lives of those less pampered. Also troubling are some of the stereotypical racial tropes used: one of the family’s business associates, as well as their amah, is described as “the epitome of inscrutability”. (It’s only now that Brown realises that her distance and efficiency were a way of dealing “with having to be constantly subservient”.)

With all the political fracas about the pro-democracy uprising in Hong Kong and the future of this highly contested region it’s apposite or perhaps hopelessly quaint to read this sentimental tribute to a lost world.

Thuy On is books editor of The Big Issue.

Down and out in Paradise: A Memoir

By Luke Williams.

Bonnier Echo, 304pp, $29.99

The Kowloon Kid: A Hong Kong Childhood

By Phil Brown

Transit Lounge, 272pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout