Love, life and crimes: these are the best books of 2024

Heading on holidays? Or looking for something to keep you entertained during your staycation? You’ll find some absolute gems on this list – as recommended by The Australian’s literary critics.

Love, life and crimes: these are the best books of 2024, according to The Australian’s literary critics.

Caroline Overington

Literary Editor, The Australian

It’s hard to choose just five books, when so many were so good. I decided to concentrate on novels, and three of my five are Australian (one Sydney, two Melbourne!)

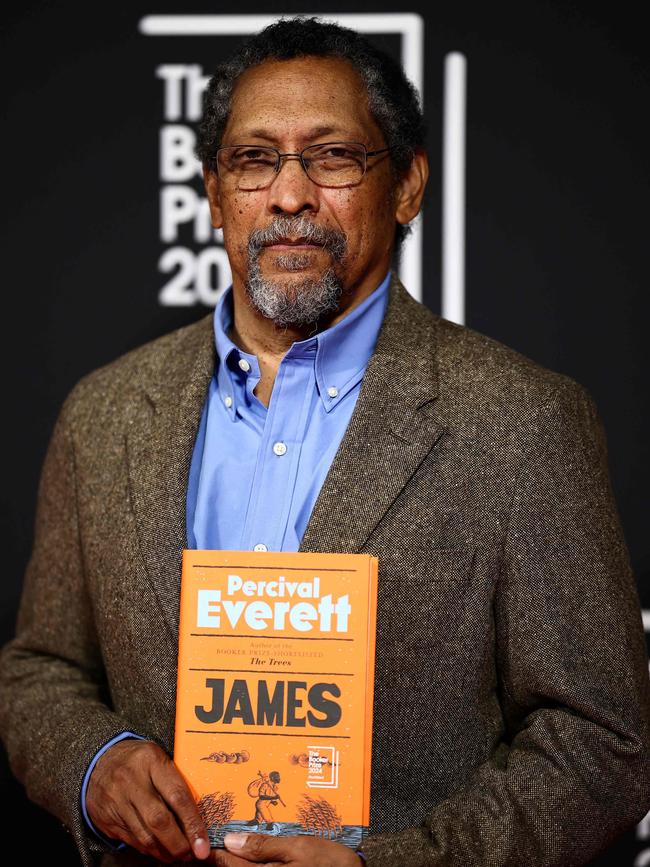

James by Percival Everett is a retelling of the Huckleberry Finn story from the perspective of Jim, or James, who takes flight ahead of the Civil War. Brutal in parts, of course, but brilliant.

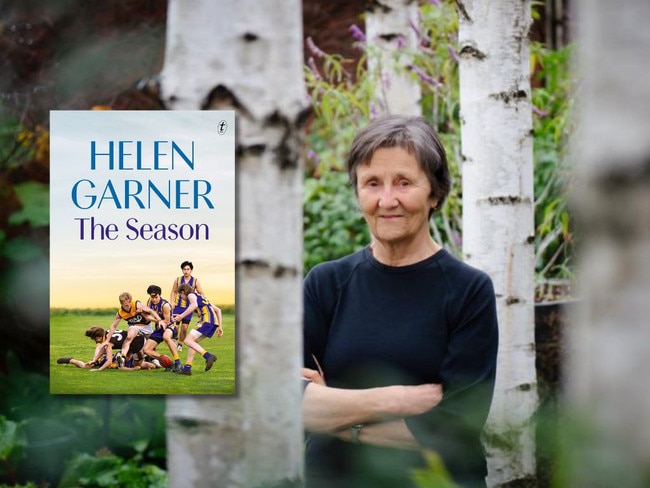

The Season by Helen Garner. A grandma (Helen) tags along to AFL training with the youngest of her grandchildren. A gift of love to men, boys, parents and grandparents everywhere.

Diving, Falling by Kylie Mirmohamadi. An artist dies, leaving $69,000 to his mistress in his will. His wife has to cope with that, while managing the rest of his estate.

Highway 13 by Fiona McFarlane. Short stories, exploring the ways in which one particular series of crimes impacted the community. Intelligent, deeply thoughtful, with gorgeous prose.

Hard Copy by Fien Veldman. A woman falls in love with an office printer. Not the photocopier! Nobody could love the photocopier. The printer.

Geordie Williamson

Chief Literary Critic

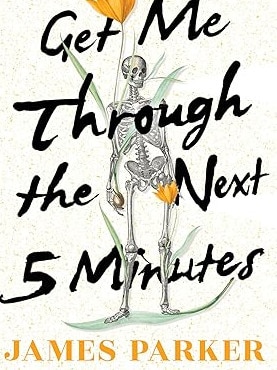

The title that brought me most joy belongs to James Parker, staff writer at The Atlantic and laureate of the Everyday. Get Me Through the Next Five Minutes (Norton) is a book of odes to mundane aspects of existence (chewing gum, dogs’ testicles, BBQ chips, crying babies) that unfurl from initial hilarity into moving poems in prose. Feeling blue? Don’t go into therapy: read this book instead.

Michelle de Kretser’s new novel Theory and Practice (Text) is her briefest, yet it contains whole constellations of thought and feeling. Is it biographical fiction, or fictionalised biography? It doesn’t matter. A condensed marvel of a novel.

But my book of the year – of many years – is Matthew Lamb’s Strange Paths. It purports to be the first volume of two dedicated to the life and work of Frank Moorhouse. One reviewer, in The Guardian, suggested that this was life writing “that may well reach, even exceed, David Marr’s Patrick White: A Life, which many consider the high-water mark of Australian biography”. But it is even more than this. Lamb has written a cultural history of post-war Australia in these pages. It is a work to put on the shelf beside Donald Horne, Dorothy Green or Bernard Smith – those who sought to treat Australian experience with the seriousness it deserves and yet rarely receives.

Samuel Bernard

Literary Agent

The Great Undoing by Sharlene Allsopp presents as a dystopian novel set in the not-too-distant-future, however its layers run deep. It is about connection, technology, surveillance, and our frightening political trajectories.

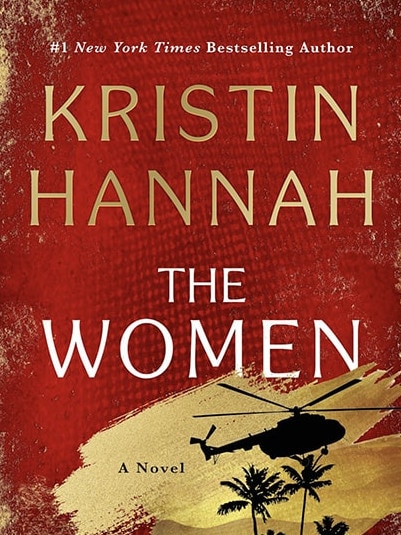

The Women by Kristin Hannah is about the incredible, powerful and all too often forgotten impact that so many women had on humanity during its darkest of days of the Vietnam War.

This Kingdom of Dust by David Dyer. I first read David Dyer’s debut The Midnight Watch with my dad, it turned out to be the last book we read together. We fell in love with Dyer’s storytelling, his exploration of the historical fiction genre, and his style. I wish my dad was around to read his follow-up because it is even better than his debut and one of my top picks of 2024.

The Whale’s Last Song by Joanne Fedler blends realism with fantastical elements in a timeless marvel. A magnetic tale of life, grief and a love song to the beauty of our natural world, it is truly a unique reading experience.

War by Bob Woodward is a frightening yet vital read about the state of global politics with a second Trump term around the corner. The political read of the year.

Peter Craven

Culture critic

Craig Brown’s A Voyage Around The Queen, a life of the late Queen in anecdotes, is an extraordinary achievement.

Anne Carson’s Wrong Norma is a dazzling collection by the woman who is arguably the greatest living poet at work in the English language.

Gabriel García Marquez is one of the greatest fictionmakers of that century and Until August is the weirdest and richest footnote to that career.

If you want the magic of the book as a physical object for the reader’s Christmas tree you can’t go past The Diaries of Fred Williams, superbly edited by Patrick McCaughey, or perhaps Nolan’s Africa with a text by Andrew Turley, both magnificently produced by Melbourne University Publishing under its Miegunyah imprint.

The Season by Helen Garner is a grandmother’s book about footy-playing boys by a woman who seems to have outgrown men.

Charmian Clift’s The End of the Morning has the casual beauty of one of the greatest essayists this country has produced, with an added anger and complexity and political edge.

In Knife Salman Rushdie tells the ghastly story of how he lost an eye to a would-be assassin, with absolute gravity and grace.

Gideon Haigh’s My Brother Jaz is the length of a long essay but it is an extraordinary work.

Stephen Downes’ Mural is a dark and brilliant book.

Kevin Hart’s Dark-Land is one of the most extraordinary autobiographies ever written, and then there are purely beguiling books like Colm Toibin’s Long Island.

Helen Elliot

Writer and literary critic

James by Percival Everett.

Everett takes the runaway Jim, from Twain’s 1884 Huckleberry Finn, re-keys him into history, and history is re-keyed into another orbit. Jim becomes James. Everett’s conceit dazzles; Jim is a forensic performance of an ignorant slave, right down to the dialect of his speech but the slave Jim is, in fact, refined James, a man of education and genuine enlightenment, as opposed to the derelict slave owners along the Mississippi pre-Civil War. Everett is some sort of genius. Original, droll, painful, upsetting in every sense.

Caledonian Road by Andrew O’Hagan.

O’Hagan’s masterpiece. Caledonian Road, here part of London where the rich live. Campell Flynn and his wife live here, his wife because she was born to live here, unlike Campbell. He comes from poor Glasgow. But intelligence, ambition, charisma and infinite slog have given him status and renown in the cultural world. But his world has become a maelstrom. Campbell’s tale is a dissection of the UK in the past few decades. The verve, the glory of O’Hagan matches the verve, the glory of Dickens.

Intermezzo by Sally Rooney.

Two Dublin brothers, 10 years apart, Peter a brilliant lawyer, Ivor some sort of chess genius, are grappling with the profound grief of their father’s death and their relationships. Peter in love with two women, Ivor falling in love. I will use the word marvellous, the only accurate word for Rooney writing about the endless depths, reversals, misunderstandings of human interactions. Nothing and everything happens. Including the best sex writing since Carrie Tiffany.

Compassion by Julie Janson.

Australia, the 1830s: an adolescent girl, Nell, searches for her mother as settlers search for land. Janson, writing from knowledge of her own ancestors, like Everett, writes against lying history. Nell has a grip on herself, and the reader from the beginning. She is fantastically, joyfully alive in every way; not victim but with her own history, her own agency. Janson’s poised and significant work needs to be on curriculum along with Toni Morrison and Alice Walker.

The Three Graces by Amanda Craig.

Three expat women live in a Tuscan hilltop town; a retired psychiatrist, a concert pianist, a veteran of Zimbabwe. They meet in the town square every Sunday morning to discuss their complex lives. One grandson wants a Tuscan Destination Wedding and he’s asked his grandmother to help. How We Live Now? Yes, Craig is the contemporary Trollope. A perfect antidote to Tuscan Disney.

Our Evenings, Alan Hollinghurst.

Dave Win is the son of Avril, a dressmaker; his dead father was a mysterious Burmese diplomat but Dave never met his father and his closeness to his mother is one of the (many) wonders of this book. At his famous school and at Oxford the mixed-race scholarship boy flourishes. He becomes an actor and now, in his sixties he reflects on the magnificence of life. Hollinghurst’s intense grasp of history, his ability to frame the indolent and callous shifts of the world, is unique. What Velazquez does in Las Meninas, in oils, Hollinghurst does in tone and pace.

Diane Stubbings

Literary critic

Richard Powers’ Playground reminds us why he one of the world’s best contemporary novelists. A breathtaking climax crowns a story that embraces AI, climate change and the extraordinary life teeming within Earth’s oceans. Powers’ strength is his ability to situate characters firmly within the chaos and promise of modern science.

In The Third Realm, Karl Ove Knausgaard continues his Morning Star series. While you sometimes wonder whether Knausgaard’s exploration of the nature of evil is perfunctory or profound, there is no escaping the tension he creates as we witness the waning borders between life and death.

Percival Everett’s James is both a glorious homage to Huckleberry Finn and a consequential – and viciously funny – re-imagining of the life and sensibility of Jim, the slave who accompanies Huckleberry Finn on his adventures.

In non-fiction, Rebecca Boyle’s Our Moon is a riveting study of the history of the moon and its crucial role in both the physical and cultural evolution of humans.

In the wake of the 2024 US election, Anne Applebaum’s Autocracy Inc. is the “must read” book of the year, demonstrating that would-be autocrats like Trump seek power not for its own sake, but for the opportunity it offers to enhance their personal wealth.

Emma Harcourt

Author and critic

Free by Meg Keneally

This is great historical fiction, written by an author at the height of her talents. Molly Thistle leaves 18th-century England for the convict town of Sydney in shackles, but her path is forged by a joyful and dogged determination to prove those who scorn her status and her sex wrong. The characters are richly layered and the brutality of colonial Australia, and specifically the treatment of the women in its care, is vividly portrayed.

Tilda is Visible by Jane Tara

Jane Tara’s debut novel stormed on to the bookshelves and into my heart. To weave a believable story about a 50-something woman in a beachside Aussie suburb whose body parts simply start to disappear is no mean feat. Tara succeeds stunningly with this funny, insightful and very readable tale.

All Fours by Miranda July

This is a wild ride of a book. Bawdy, honest, funny, it’s a deeply personal account of what happens when one woman spontaneously exits her life to discover who she really is beneath the layers of normalcy. Fearlessly written and brilliant.

Psykhe by Kate Forsyth

The stable of myth-lit continued to expand this year with Forsyth’s immersive retelling of the myth of Eros, the god of desire, and Psykhe, the mortal woman who captured his heart. The world of the ancient myth is very much alive in the historical detail but in this author’s experienced hands, the tale becomes a deeply human one of a woman who defies the gods and must undertake a dangerous quest to save the man she loves. Great summer read.

The Beauties by Lauren Chater

This is a book that asks if beauty is power, does the woman who wears the face wield the power? It’s also about sex because, in 17th-century England, that’s how beauty was traded. Meticulously researched and full of fascinating facts about the work of portraiture, this is historical fiction with a dash of glam and highly entertaining.

Andrew Leigh

Federal Member for Fenner and bibliophile

Annie Bot by Sierra Greer

A compelling and chilling read, that’s both relevant to our technological era and modern-day debates over violence and control.

The Hypocrite by Jo Hamya

A sharp analysis of generational differences over sexual norms, set in London and Sicily (with a beautifully clever ending).

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

If you thought that Irish fiction had become more upbeat since Angela’s Ashes, The Bee Sting will set you straight. An insightful, contemporary, gut-punch of a novel.

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan

Chance and consequence collide in a tale about the past, with lessons for the future.

The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store by James McBride

A tale of Black and Jewish people living on the margins of the white-dominated town of Chicken Hill. Come for the plot (a body is found in a well), stay for the characters (Moshe and Chona, Dodo and Monkeypants).

Paul Monk

Writer, critic, poet

Six priceless reads in 2024 include four published this year, one last year and one published eight years ago (2016), but finally read this year. In no particular order, the six are:

Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Living on Earth

Life, Consciousness and the Making of the Natural World. This is a tour de force of natural philosophy and an invitation to live at the interface between science, philosophy and poetry. Not to be missed.

Anne Applebaum’s Autocracy Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World

Applebaum is one of our redoubtable champions of liberty and accountable government in a time of neo-authoritarianism and naked aggression. This is a clarion call to us all.

Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.

Bravely taking on the woke revisionists, Biggar critically examines the realities of colonialism and weighs them scrupulously in the scales of a Christian moral conscience. The findings are eye-opening.

Sean McMeekin’s The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908-1923.

McMeekin is one of our most path-breaking revisionist historians of the upheavals of the 20th century. This book, drawing on long-closed archives, breaks new ground in several directions. Compelling reading.

Nate Silver’s On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything.

From one of the maestros of prediction markets and probability theory, himself an accomplished poker player, a treatise on risk for a 21st century reader. Masterful.

Sam Leith’s The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood

Reading. The loveliest of books about the loveliest of stories and the often unlovely lives of their authors. Utterly enchanting.

John Kinsella

Writer and poet

Though it came out late 2023, I didn’t receive a copy of The Letters of Seamus Heaney until early 2024. Christopher Reid has done an excellent job in gleaning just what’s necessary to show the verve, learning, acuity, irony, wry humour and directness that made Heaney such an interesting and informative letter writer, be it for private or work purposes.

I was overwhelmed by J.H. Prynne’s Poems 2016-2024, which manages to be massive and iconoclastic at once, carrying this late-modernist’s work into new zones of innovation and action.

Nam Le’s deconstructive 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem was a surprise to me – I didn’t see it coming, but was delighted when it did.

Kwame Dawes’ magnificent and revelatory Sturge Town: Poems is a must. I have worked with Kwame on making (other) books for years, and yet the power of his work is always refreshing and often confronting.

Gawimarra: Gathering (UQP, 2024) by Jeanine Leane is an essential book of anti-colonial poetry that deeply affirms Country.

And finally, novelist-poet Alan Fyfe’s technically accomplished first book of poetry, G-d, Sleep, and Chaos, which is full of grit, the “syntax of West Pinjarra”, out-of-kilter imagery, and a street-smart, sharp-tongued wisdom.

Ray Bonner

Bookshop owner

Rebellion: How Antiliberalism Is Tearing America Apart, by Robert Kagan.

When anyone asks me to “explain America, how Trump be so popular, why is America so divided”, I give them this book. The Founding Fathers fought about the role of government, about religion and race – 250 years later the battles continue.

I Brought the War With Me: Stories and Poems from the Frontlines, by Lindsey Hilsum.

One of the greatest war correspondents of her generation, Lindsey took a book of poetry with her wherever she went – Iraq, Gaza, Ukraine, China, Uganda, Syria, Rwanda, Sudan, Somalia – marrying poetry with reporting.

The Message, by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Searing and controversial. One of America’s leading public intellectuals, he went to Dakar where he found the ghosts of his enslaved ancestors; to South Carolina where a school wouldn’t teach his best-selling book Between the World and Me; to Palestine and Israel which led to a rethinking of his call for reparations.

James by Percival Everett.

Based on Mark Twain’s classic Huckleberry Finn, Everett tells the story of their adventures on a raft in the Mississippi through the escaped slave. Hilariously funny at times. Also, tragic.

Juice by Tim Winton.

Proving again why he is one of Australia’s greatest storytellers. Set a couple of hundred years hence, when “climate change” has produced summers so hot that people are forced to live underground. A 17-year old is recruited by an SAS-like cult, and sent on missions to “acquit” the oil company CEOs responsible.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout