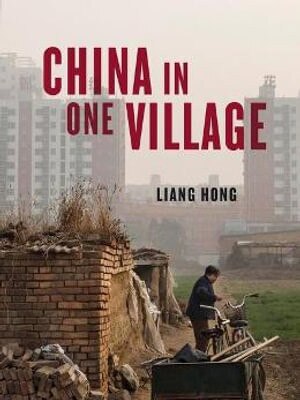

Losing the heart of China

At a time of serious tensions between Canberra and the China of Xi Jinping, this is a perspective Australians will never get from alarming reports about our current trade or military concerns.

At a time of serious tensions between this country and the China of Xi Jinping, this is a book that will humanise China and enable readers to get a depth of perspective they will never get from reading alarming reports about our current trade or military concerns. It is a book all Australians should rush out to buy and read.

Liang Hong is a literary scholar at Renmin University (People’s University) in Beijing. The village she focuses on, with exquisite attention to detail and stunning empathy for the lives of those being overwhelmed or left behind by modernisation, is the one in which she grew up. Her book opens and closes with personal reflections on the meaning of what Simone Weill, a lifetime ago, called the need for roots.

The quality of those reflections brought to mind the quality of Proust’s famous search for lost time. She doesn’t write in the style of Proust, but the concerns and insights she shares with us are distinctly Proustian and make her someone one I would love to meet and converse with.

When she introduces us, on the other hand, to the social world of those who have lived and still live in the village, we are in a world far more reminiscent of Zola or Faulkner than of Proust.

When she shows us how dislocated and uprooted so many individuals from the village have become by the vortex of China’s rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, the literary sensibility is wonderfully rich. But the social setting is Dickensian.

She herself expresses deep concerns about the massive damage that has been done to the village (and countless others like it) by the whirlwind of “progress”. But she doesn’t draw this picture based on sociological or economic, to say nothing of ideological abstractions. She bases the entire thick description on months of living in the village and interviewing its inhabitants – including many she had known when she was growing up there.

Many literary classics sprang to mind as I read the book, particularly where she is describing extended interviews with women about work, marriage, child-bearing and raising, I was vividly struck by the resemblance between the simple lives so illuminated, each in a few pages, and the short stories of Guy de Maupassant or the novels of John Steinbeck.

The overarching concern of Liang Hong is with the cultural and moral disintegration of rural life, as exhibited in the decay of her old village, in the years since she went to college and got an academic career in the national capital, a beneficiary of the growing opportunities in China as its economy expanded.

She has a very discerning eye for detail, but the teacher in her centres the story she has to tell on the fate of the village school that she herself had attended some decades ago.

“After the closing of the village school,” she writes, “ … village culture began to collapse from within. Only its form remained. The village itself was dead. The implication is this: China’s smallest structural units have fundamentally broken down and individuals have lost the stabilising force of the land.

She observes that at just the point where a whole, hardworking, displaced generation of parents can afford to send their children to school and even college, children have lost interest in studying, reading or getting an education. They want to get jobs in their teens and simply become part of the big boom and the wider world beyond the village.

Reading Liang Hong, I found myself thinking of so much other, less readable or less perceptive scholarly works on modern rural China. Most particularly, my mind went back to one of the classics of pro-Maoist writing on the subject: William Hinton’s Fanshen (1966), which extolled what he described as the progressive transformation of rural China between 1949 and 1965.

One might construct a whole undergraduate course on the subject by juxtaposing Hinton’s Marxist paean to Maoism of 1966 and Liang Hong’s bleak description of rural China in the early 21st century.

The omissions of Hinton stand out, but the profound irony of the fate of the peasantry in China under a party that seized power seventy-two years ago in the name of peasant revolution are poignant.

Mark Elvin’s brilliant study Changing Stories in the Chinese World (1997) showed how, since human beings live inside stories about themselves, the past two centuries in China can be understood through reading Chinese novels and plays and poems.

Liang Hong shows us rural stories being obliterated through the very process of rapid modernisation. She nowhere refers to Karl Polanyi’s classic The Great Transformation (1944) about the industrial revolution in England but it looms behind her beautiful book at every point.

Read her and get a feel for China right now.

Paul Monk is the author of Thunder From the Silent Zone: Rethinking China (2005), Sonnets to a Promiscuous Beauty (2006) and Credo and Twelve Poems (2014), among other books.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout