Margaret Thatcher: Looking behind the Iron Lady

Despised and condescended to, Margaret Thatcher was a woman of great fierceness and frailty who changed the world, through sheer power of mind.

Every so often a work of non-fiction commands your absolute attention, even if you have no automatic sympathy for its subject. Margaret Thatcher was a nightmare to many people in Britain during the 10 years she was prime minister. The grocer’s daughter from Grantham was despised by the university she attended, Oxford, and condescended to by the posh boys of the Conservative Party she led, some of whom came to see her as a bigot and a Euro-hater. She was so reviled in some parts of England, especially the Midlands where she crushed the miners and the north, that when she died in 2013, Ding Dong the Witch is Dead was a top 10 hit.

But the image of her is indelible in the records of historical memory and will be in perpetuity, one suspects, partly because her biographer, Charles Moore, has captured the glory and grimness of the woman the Russians called the Iron Lady in such detail, with such a sense of comedy and such compassion. He paints a magnificent portrait of a woman of great fierceness and frailty who refused to acknowledge any of the blinding limitations of her vision, who nonetheless changed the world, probably forever, sometimes for the better, through sheer power of mind.

She could not rightly own her horror of Europe, but she constantly resisted her chancellor Nigel Lawson’s attempts to go along with the ERM, which tallied with the Deutschmark and effectively led the way towards the acceptance of the euro and the idea of a common currency.

It didn’t help that she hated the Germans with a passion and a prejudice that derived from her wartime childhood. When Helmut Kohl, the man who reunited Germany, remarked that in beating Britain at football, Germany had defeated the United Kingdom at its favourite pastime, she snapped, “Well, we’ve beaten you twice at yours” — meaning the world wars, no less.

She was actually disturbed by the prospect of reunification. At one stage she called a conference to anatomise the German soul, at which Hugh Trevor-Roper, the author of The Last Days of Hitler, who came unstuck over the authenticity of the so-called Hitler’s Diaries, actually said to her: “I was in Germany in 1945, and if you had told us then that we would have a united Germany as part of the West, we would not have believed our luck.” Her foreign secretary, Douglas Hurd, spoke of her “extravagant suspicions of Germany”, and at some level she thought the Germans were the heirs of Hitler.

To be fair, she was also partly concerned about Mikhail Gorbachev, the last of the Soviet Russian leaders, of whom she was the most significant Western ally. She described him in this context as “really making an effort”, and said to US General Colin Powell, when he told her Gorbachev had said to him he would establish the rule of law in Russia “regardless of the consequences”: “Oh, dear boy, don’t take that seriously. Even I say silly things like that from time to time.”

It’s somehow that trick of capturing the throwaway remarks of Thatcher and this immense cast of formidable and furtive characters that makes Moore’s book such a delight and such a monumental and absolutely credible account of a historical landscape with a dominant figure.

He tells the story of someone who’s written her quite a nifty speech invoking the Monty Python parrot. Just before she gets up to speak, she dumbfounds her colleague by saying: “This Monty Python, he’s one of us, isn’t he?” She gets the laugh but has no idea why.

Moore says at one point that she was a combination of high principle and base suspicion. Anyone who’s getting on will remember how abrasive and alienating Thatcher could be, yet we know the world we inhabit was partly created by her. She was utterly adamant when meeting other Commonwealth government leaders that she would not accept sanctions against South Africa. And she would just say, about being the only leader who would not accept them: “If it is one against 48, I am just sorry for the 48.”

On the other hand, she was very shrewd at realising that F.W. De Klerk, who finally moved against apartheid, was someone she could work with, and Nelson Mandela passed on a message through a lawyer emphasising his “appreciation of your prime minister’s role in opposing apartheid”.

She was in many respects an utterly extraordinary figure. Who would have thought, who indeed remembers, that it was Thatcher, just two weeks before she was forced out of office by a coup in her own party, who said: “Carbon dioxide emissions must be curbed and there should be a legal requirement for a substantial proportion of electricity from non-carbon sources.” As an ex-politician, she changed her tune, but so what? Who but Thatcher would have had the audacity in the first place?

Of course, she was capable of political idiocies like the poll tax, which was massively unpopular and utterly destroyed her because it basically aimed at redressing the excesses of Labour councils, but in fact turned out to be a potentially massive burden on actual households.

Yet she also shaped the apprehension of the world so that the significant fraction of liberal-minded people who have trouble with the very idea of Jeremy Corbyn-style socialism are influenced by the ideas she made mainstream, which represented at least a quite drastic deconstruction of the old Tory/Labour consensus on the welfare state.

Tony Blair, one of nature’s third-wayers, said of Thatcher: “Her finest achievements had been as a moderniser against old-fashioned collectivism — for instance, recognising that some industries, like telecoms, the state should be out of and that trade unions should operate within a legal framework.”

Blair was explicit about his debt to Thatcher; he knew instinctively just how big-time a politician she was. “He thought Ms Thatcher was the most formidable opponent that Labour had ever faced,” Moore writes, and he quotes Blair saying: “She could still have won the 1992 election. She was able to govern with the strength of party unity her successors were lacking — and an enormously clear sense of direction. They don’t have it any more.”

Chris Patten, the man Gareth Evans declared was the greatest prime minister Britain never had, the man who fought like a lion as the last governor of Hong Kong, had an impassioned horror of Thatcher’s last days, but he changed his mind about how they got rid of her. “We were mistaken,” Patten said. “The Conservative Party would have been better served if she had been dispatched by the electorate.”

As Moore says, the manner of her fall was a disaster, and 30 years on, with Brexit, “the Conservative Party has still not recovered from the assassination of its most successful peacetime leader”. He adds: “They created an unforgettable tragic spectacle of a woman’s greatness overborne by the littleness of men.”

Almost at the finish, her Labour MP mate, Frank Field, came to Number 10 Downing Street. “I’ve come to tell you you’re finished,” he warned her, “[Michael] Heseltine is hoovering up the votes. You can go out on a high note. If you haven’t resigned by tomorrow afternoon they’ll tear you apart.”

So she resigned. Even Kohl acknowledged the greatness of the woman who had been formed by her horror of Hitler. The Queen, who had never been a fan (only the Queen Mother was), was seen to be very considerate to her. As soon as Thatcher got back to Number 10, after her downfall, she ran for the bathroom and broke down completely. “It’s when people are kind to you, you feel it most. The Queen has been so kind to me.”

Moore delineates the twilight years with a fine sense of elegy. She was the only non-American to speak at a president’s funeral, and she did this for Ronald Reagan, who was always a favourite beau among potentates.

In the late days she was often uncertain of where she was and what to do. At her 80th birthday party, which the Queen attended, Her Majesty said after the speeches: “I’m afraid I must go.” “What a good idea,” Thatcher replied, “I think I’ll go too.” “You’d better not,” the Queen answered. “It’s your party.”

It was never quite her party, the British Tories she ruled with a rod of iron. It’s not hard to understand why Glenda Jackson, at her most Elizabeth R-like, should have denounced Thatcher in the House of Commons at the news of her death.

Yet she trod the world stage like a titan who was also a woman of modest background. She had the respect of Gorbachev, of Lech Walesa, the great Polish democrat and trade unionist, even of Mandela. Whether or not Britain is at the edge of ruin or is about to witness some impossible-to-imagine new age, they will remember Margaret Thatcher. She was made of sterner stuff than anyone she stood up to fight.

Peter Craven is a cultural critic.

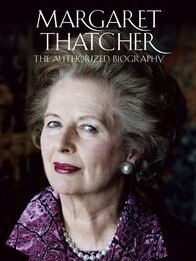

Margaret Thatcher: The Authorised Biography, Volume III: Herself Alone

By Charles Moore

Allen Lane, 1008pp, $65 (HC)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout