Literary plagues: Albert Camus, Dean Koontz, Geraldine Brooks, Janette Turner Hospital, Chris Womersley, Jim Crace

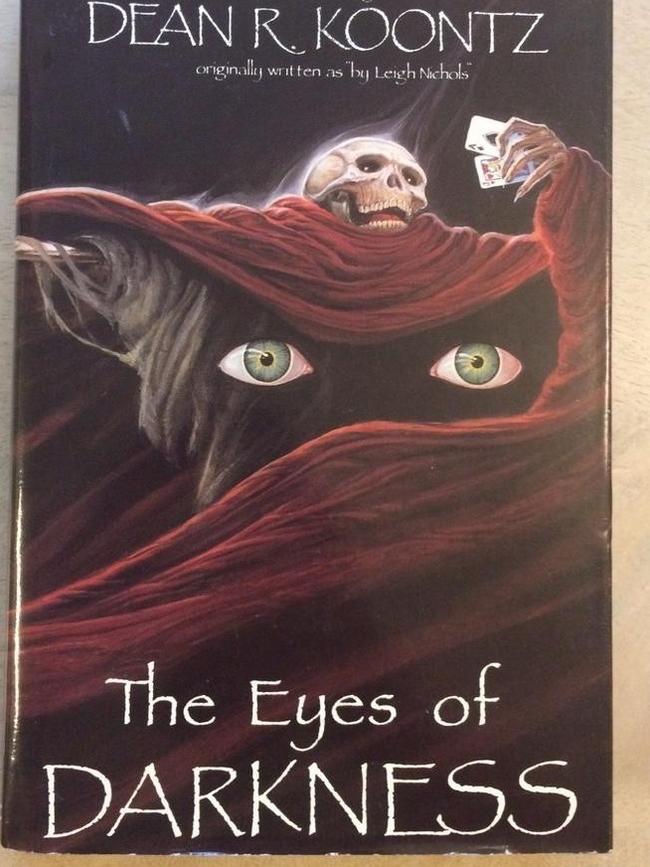

You may have noticed a story on social media that bestselling American novelist Dean Koontz predicted the coronavirus in a 1981 book.

You may have noticed a story floating around on social media that bestselling American novelist Dean Koontz predicted the coronavirus in his 1981 thriller The Eyes of Darkness. It’s an intriguing bit of literary speculation for a couple of reasons.

That 1981 novel was published under Koontz’s early nom de plume, Leigh Nichols. It’s about an American woman investigating the death of her young son. As the plot thickens there is mention of a Russian biological weapon called Gorki-400, named after the city where it was created.

The novel was reprinted in 1989 under Koontz’s name and in this version, the one with which most readers are familiar, the name of the biological weapon was changed to Wuhan-400. It was cooked up by a scientist, Li Chen, and originated in Wuhan, as did the latest coronavirus. Koontz shifted the location of the weapons lab after the break-up of the Soviet Union.

So there are some similarities. There are also some differences. Gorki-400/Wuhan-400 is a manufactured biological weapon that attacks the brain. It kills 100 per cent of its victims, a far higher mortality rate than coronavirus, which hits the respiratory system.

Here’s a bit from the novel: “The virus migrates to the brain stem, and there it begins secreting a toxin that literally eats away brain tissue like battery acid dissolving cheesecloth. It destroys the part of the brain that controls all of the body’s automatic functions.’’ That sounds more lethal than COVID-19, as the coronavirus is now called.

Of course that could change. We are learning more about the contagion every day. At the time of writing Australia had suffered its first death, the NSW Health Minister was warning people not to shake hands or kiss and supermarkets were running short of necessities such as toilet paper due to panic buying.

So did Koontz predict the plague? I decided to ask the man himself. He told me he had been so swamped with inquiries that he had decided not to buy into the story. But he added that he thought people were giving him a bit too much credit. “Re the coronavirus, my powers as a prognosticator have been greatly exaggerated, considering that I can’t even accurately predict what I’ll have for dinner this evening.”

Koontz has a new novel, Devoted, out in April. I hope to talk to him more then, assuming civilisation is still in place.

Koontz is not the first novelist to write about an epidemic, nor will he be the last. I imagine a lot of typewriters are revving up as we speak.

Readers will have their own picks, but thinking of Australian writers, the books that come to mind are Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks, Due Preparations for the Plague by Janette Turner Hospital and Bereft (Spanish flu in this case) by Chris Womersley. I must also mention The Pesthouse, by the gifted and under-appreciated English writer Jim Crace.

However, the one I decided to re-read this week was — and no prizes for guessing this — Albert Camus’s The Plague, first published in 1947 as La Peste.

I dug out my copy, a 1960 Penguin paperback translated by Stuart Gilbert. It has a gritty, grotty cover illustration by Michael Ayrton. I have included a photograph of it here because the first thought I had on pulling it from the shelves was how wonderful it was to read the same copy I first read decades ago, even with the now-loose pages.

Some books definitely have a physical hold, I think. Rearranging my household bookshelves last weekend I tried to be brutal about eliminating double copies. I was, yet now and then I crumpled.

There is no way I am saying goodbye to my copy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, for example, even though it is in far poorer condition than my other half’s copy. So both remain on the shelves, not far from Camus, as the alphabet demands.

My second thought, a few pages into The Plague, was what a deep privilege it was to be back in the world of Camus. I know I am reading a translation but nevertheless I feel, rightly or wrongly, that I am inside the mind of the great French writer, who won a Nobel prize in 1957. Less than three years later he died in a car accident, aged 46.

The Plague is set in the French Algerian town of Oran, around the time of publication (the opening sentence puts the year as 194-). It is thought the inspiration was a cholera epidemic in Oran in 1849, after French colonisation.

The town, which is on the water but does not face it, is described as “treeless, glamourless, soulless”. The main character is the local doctor, Bernard Rieux. The tale, the chronicle of the plague, is told by a narrator. The story moves into stride at the start of chapter two when Dr Rieux leaves his surgery and feels “something soft under his foot”. It is a dead rat.

Soon lots more rats emerge and die rather miserably. When the doctor’s wife asks about this, he replies, “I can’t explain it. It certainly is queer … but it’ll pass.” Soon after another character, Jean Tarrou, a mysterious new arrival, a man of private means (how I love that old-fashioned expression), observes that the rats, dead or alive, are not their problem but are rather “the porter’s headache”.

He and Dr Rieux are wrong. The disease spreads to people. The porter becomes infected and dies. His death “marked the end … of the first period, that of bewildering portents, and the beginning of another … in which the perplexity of the early days gradually gave place to panic”. That sounds familiar right now.

The death toll starts to rise. Dr Rieux meets the Prefect and other local officials. They fail to reach agreement. When Rieux leaves the meeting, Camus moves into a higher gear. “Some minutes later, as he was driving down a back street redolent of fried fish and urine, a woman screaming in agony, her groin dripping blood, stretched out her arms towards him.”

By the sixth week, the weekly death toll has risen to 345. Oran has a population of 200,000. I decided to relocate this to Canberra, which has about twice as many people. Imagine that: about 100 people in Canberra succumbing to plague every day. It sort of puts it in perspective. And this is early days in the novel, where for the people of Oran “plague was … an unwelcome visitant, bound to take its leave one day as unexpectedly as it had come’’.

Alarmed, but far from desperate, they hadn’t yet reached the phase when the plague would seem to them the very tissue of their existence.

There will come a time when the town runs out of coffins, let alone toilet paper. I’m not suggesting it’s the same with COVID-19, but it is a reminder of horrors that have been and ones that could come. Interestingly, the weather is significant in The Plague. The town is too hot, too dry, too muggy, too windy. There is no rain, then too much rain. Thinking of the best word to describe the weather in this novel I decided on hostile. That, too, feels familiar.

In the first weeks of the coronavirus outbreak the headline news was the negative effect on the stockmarket. Early in The Plague, we’re told the citizens of Oran “work hard, but solely with the object of getting rich. Their chief interest is in commerce, and their chief aim in life is, as they call it, ‘doing business’.’’

This changes. Camus writes of the human cost, never more so than in a passage where a young boy suffers and dies, his “small mouth, fouled with the sordes of the plague and pouring out the angry death-cry that has sounded through the ages of mankind”. That is hard to read.

That’s not to say The Plague is humourless. I like it when the local men decide the best response is to drink heavily. Wine, they tell each other, is the best protection against infection.

“Every night, towards 2am, quite a number of drunk men, ejected from the cafes, staggered down the streets, vociferating optimism.”

And the funniest character is government clerk Joseph Grand, who spends his private hours rewriting the opening (and I think only) paragraph of his proposed literary work. It involves a woman on a horse on the Bois de Boulogne. When someone observes that he’s writing a book, Grand replies, “Something of the kind. But it’s not so simple as that.”

He is deeply troubled by this “unavailing quest”. I immediately checked my shelves and, yes, Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, published five years before The Plague, is there, daring me to climb towards it.