Light exhibition from the Tate opens at ACMI in Melbourne

Out of the shadows comes a new exhibition exploring how artists from Turner to Turrell have responded to the most elusive of natural phenomena, light.

When you stand in front of one of Turner’s paintings – of a stormy maritime scene, or a steam-belching iron horse – possibly the last thing you think is that this is an artist of the Enlightenment. Turner was a painter of storms and tempests, of smoky haze and vivid sunsets. Everything is atmosphere, emotion and high drama. He’s a romantic, through and through.

So it’s a surprise to see some of the small works on paper that Turner produced in the early 1800s when he was a lecturer at the Royal Academy. He was a teacher of perspective, and made the drawings as demonstrations of how to depict the interplay of objects, light and reflection. They show globes of polished metal and clear glass, some half-filled with water, and how differently they reflect the interior of a room and light from a nearby window.

Turner’s concern with scientific observation seems at odds with the popular view of him as a visionary and somewhat eccentric artist who was determined to go his own way. The lecture drawings show how his empirical study of light and reflection informs the atmospheric effects in his paintings, which in turn would inspire the Impressionists.

“He is looking at perspective, he is looking at how light interacts with shadow, or generates shadow, how a cube or a sphere casts shadow in different ways,” says Kerryn Greenberg, the curator of a new exhibition about light coming to ACMI in Melbourne.

“You have an interior being depicted – but it’s not being depicted, it’s a reflection of the interior, with this nice interplay between light and shadow, and the third element is the spheres themselves.”

Turner’s lecture drawings and large canvases, such as his biblical landscape painting The Deluge, are coming to ACMI from the Tate in Britain, in an exhibition called Light. Drawing on works from across the Tate’s collection, Light aims to show how artists have responded to the effects of light or have harnessed it as an artistic medium.

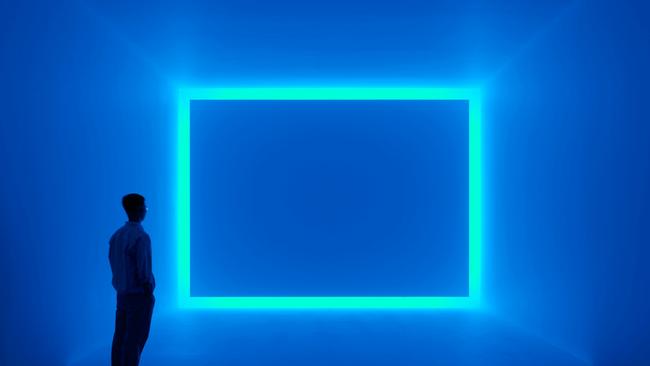

The show includes paintings and works on paper, but also photography, film, kinetic sculpture and light installations, such as the spectacular James Turrell work, Raemar, Blue.

Turner, of course, is one of the most important artists in the Tate’s collection. His paintings were bequeathed to the British nation on his death in 1851, and eventually entered the collection of the National Gallery of British Art, now known as the Tate.

“He was described as a painter of light, and he drew on a lot of scientific theories, and on his own studies of reflection and refraction, to develop his techniques,” Greenberg says. “The drawings haven’t been seen very much, so for me it was fun to bring them out of the collection. Normally, it is the big dramatic paintings that get the most attention. But I thought that these diagrams show in a simple way not only how artists think about light, but how they translate what they are seeing onto paper – and, in this case, training the next generation of students to do the same.”

The exhibition presents some interesting juxtapositions and contrasts. Turner and John Constable were contemporaries, but how very different their manner of treating the landscape. Constable was not interested in making heroic pictures but in rendering the countryside, sea, sky and clouds with honesty and sincerity. He is represented in the show with two paintings – including the seascape Harwich Lighthouse – and a series of mezzotints of his paintings by David Lucas which have the effect of heightening the contrast between light and shadow.

Greenberg points out an interesting similarity between the work of Turner and modern artist Liliane Lijn. Her 1968 kinetic sculpture Liquid Reflections could almost be a working model of Turner’s lecture slides. In it, Perspex balls or globes appear to float on a rotating turntable of liquid paraffin. The whole is lit from the side with a strong beam of light, creating shadows and reflections.

“She is looking at the same thing as Turner: how does light behave on a surface,” Greenberg says. “The spheres on the liquid paraffin are moving and generating their own luminosity and also reflecting the light that’s being projected onto them. So it’s interesting that these artists are working so far apart and yet still are in a sense exploring the same thing.”

An exhibition of fine art may seem an unusual choice for ACMI. The museum at Federation Square, otherwise known as the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, is mostly concerned with media such as film, video and animation – not Old Master paintings. That said, there’s an element of happy opportunism in ACMI hosting an exhibition from the Tate – because why wouldn’t you want a show of historic and contemporary works from that great collection? – and there’s also an art-historical rationale. Katrina Sedgwick, the former director of ACMI who now heads the $1.7bn redevelopment of Melbourne Arts Precinct, explains the concept this way: light is the element common to Old Master paintings and to motion pictures – and indeed to all visual arts.

Artists – whether painting in the sunshine, or working with artificial illumination in a studio – use light and shadow to help create tonal contrast and pictorial drama. Similarly, cinematographers have to rely on natural or artificial light and its reflection onto light-sensitive film or an electronic sensor when making movies, film clips or video installations.

What’s fascinating in this exhibition is to see how artists since the late 18th century have used light and its opposite, darkness, in the service of narrative drama or the depiction of atmosphere, optical effects and abstract shapes.

From Turner’s depiction of the hazy skies of 19th-century London, blanketed in smoke and fog, Monet picked up clues for his own paintings that capture the effects of light at different times of the day and weather conditions. In the Light exhibition, Monet is represented with two paintings made within a few years of each other. Poplars on the Epte, from 1891, shows a strong contrast between the azure sky and white cumulus clouds. The other picture, The Seine at Port-Villez, 1894, demonstrates a different kind of tone, misty and quiet, that is created through his treatment of light.

Greenberg says light obsessed both Turner and Monet.

“Monet was often looking at the same subjects – whether it was Rouen Cathedral or the haystacks – and analysing them, and working on a dozen paintings at a time, through the day, shifting between one canvas and the next canvas, so that he was constantly building up the surface and capturing what he was seeing at a particular moment in time,” she says.

“That single-mindedness is also seen in Turner with his sketches and watercolours, where he is trying to capture that sense of atmosphere. So Turner is definitely a precedent for the Impressionists. It was important that Impressionists should feature in the show, and to think about how that forms part of the narrative – they were critical in rethinking how light is captured.”

The painstaking analysis of light and colour undertaken by Georges Seurat in his large canvases – such as Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte – was influential on other artists.

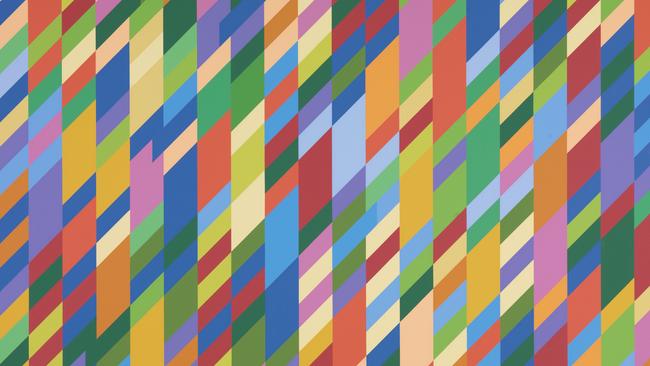

While Seurat is not represented in this exhibition, one of his followers is. Bridget Riley is usually understood as a founder, if not the best-known exponent, of optical art. In 1959 she copied Seurat’s painting The Bridge at Courbevoie and learned about his reduction of a scene into points of colour, and especially the relationships between different complementary colours.

She went several steps further, using similar colour relationships but in a purely abstract form, in her 1993 painting Nataraja. It is an arrangement of blocks of individual colour that can be read vertically and diagonally – the colours give the composition its dynamism and somehow hold it together.

“Interestingly, Bridget Riley doesn’t like the term op art being applied to her – even though she is often seen as being a key proponent of op art,” Greenberg says of the British artist, now in her 90s.

“She was not only seeking to represent light, but was also manipulating light and colour. Having these very carefully positioned bands or colour, or fields of colour, she is thinking about the relationship between each element and how it is making your eye move and giving a sense of the painting itself moving.”

The Light exhibition is drawn from the Tate collection but has never been shown at that multi-venue institution. It was designed as a touring exhibition and was one of the inaugural shows at the Museum of Art Pudong, in Shanghai, where the Tate was a consulting partner.

At ACMI, where the exhibition is part of the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series, it will be accompanied by a program of talks and public events. In two separate events, cinematographers Ari Wegner (The Power of the Dog) and Warwick Thornton (Samson and Delilah, Sweet Country) will discuss how the treatment of light is a fundamental aspect of filmmaking. Sound-art organisation Liquid Architecture will stage a performance in response to Lis Rhodes’s installation Light Music, and a series of films by Oskar Fischinger will explore his experiments in abstract animation and immersive environments.

The 20th century, with its innovations in art, technology and media, is where developments start moving at light speed. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy was a teacher at the Bauhaus in the early 1920s and experimented with the abstract possibilities of photograms, using objects to cast shadows directly onto light-sensitive paper. But he was also a proponent of light and optical instruments – not only the camera, but also microscopes and even radiography – being tools for making art.

The show includes works by other artists connected with the Bauhaus, Josef Albers and Gyorgy Kepes.

“Moholy-Nagy used to say that light will bring forth a new form of visual art, and I think you see that with the photograms, and in the sculpture that he made, Light Prop for an Electric Stage,” Greenberg says.

“We don’t have that in the show, it’s an extremely temperamental kinetic sculpture, but we do have the film that Moholy-Nagy made in 1933 which is using the Light Prop and showing how it works. You see the light interacting with the sculpture and how it is throwing light onto the walls.”

Later works in the exhibition will allow visitors to immerse themselves in mind-bending constructions of light and space. Olafur Eliasson’s Stardust Particle is a sculptural construction of reflective stainless steel, glass and light – like a shooting star suspended in space. James Turrell’s Raemar, Blue will see people enter a pristine white room which is bathed in a deep blue glow. Turrell has said that works such as this were inspired by his time as a pilot, which gives rise to fanciful notions. You can imagine a pilot in his flying machine, with no reference to the ground beneath him, and all around him the blue-painted blue.

“You are bathed in this glow, in a very white space, and you can’t quite tell how deep it is – it’s a little bit disorienting,” Greenberg says. “When I see a Turrell work, I want to understand how the effect is achieved. How is this happening? Because it doesn’t feel natural, and you want to understand how the trick is made.”

That promises to be one of the pleasures of the ACMI exhibition. Light is all around us – but elusive, evanescent. To capture it in paint, or to bend it into a sculpture, is the wonder of art.

Light is at ACMI, Federation Square, Melbourne, from June 16 to November 13.