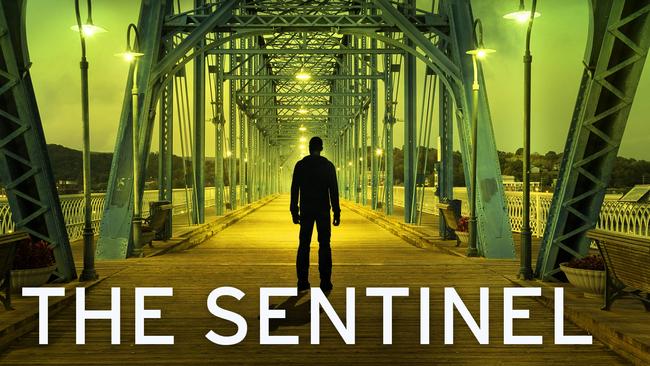

Lee Child’s The Sentinel proves the family firm is in good hands

After all but retiring, Lee Child handed his hard-bitten hero Jack Reacher over to his brother to write. Incredibly, they’ve pulled it off.

He’s back! Admittedly, since it’s only the customary 12 months since his last round of strong black coffee and vicious biff-ups, Jack Reacher’s return to drifting into an American town, righting some wrongs and then drifting out again may not take regular readers by surprise.

However, that in itself is quite an achievement here. Because while Lee Child’s hard-bitten hero is still enacting forensically described ultraviolence on all manner of bad guys — with a few knocks to a bad gal or two as well … he’s no chauvinist — Child himself has more or less retired after selling more than 100 million books.

The Sentinel is the 25th Reacher novel but the first to be written with Child’s youngest brother, the thriller writer formerly known as Andrew Grant (Lee’s real name is Jim Grant). Lee’s name is in bigger print, but Andrew, 14 years his junior at 52, is very much the main writer here.

Does this act of filial ventriloquism come off? After an effortful prelude in which Reacher beats up a nasty Nashville bar owner on behalf of the band he has ripped off, it pretty much does.

I won’t pretend that The Sentinel rivals Lee’s early hot streak. But then Lee, by his own admission in Heather Martin’s new biography, The Reacher Guy, was struggling to do that of late. And although Andrew takes on much of Lee’s artful simplicity of language and fares well with the set-piece violence, the new Reacher is slightly wittier and chattier than we are used to.

What we have here, once the throat-clearing is done, once our baddie-bashing former military policeman and his new allies are trapped into their rats-in-a-maze plot, is a thoroughly entertaining, mid-ranking Reacher adventure.

What’s it about? It’s only a few minutes since I put the book down, but already I’m hazy about the details of what went on. I’m fairly sure it involves a disgraced local IT worker, ransomware, a lot of sweating after a missing set of servers, various ruthless Russian operatives, a hi-tech plot to destabilise American elections, but also some Nazis and Soviet spies and FBI operatives. That sort of thing.

Heavens, though, when the world is crumbling, it’s good to have some of Reacher’s brutal certainties back. Pull back to observe the plot and it may all appear higgledy-piggledy in its construction. What matters, as before, is the intensity of the experience while you are in Reacher’s mindset.

Few other best-selling authors would dare to bore you by detailing the length of their hero’s shower routine (a relaxed 14 minutes here). Yet that is of a piece with succinct yet avowedly thorough descriptions of restaurants, motel rooms, mansions, bunkers, junk yards, car parks and booby traps.

So when the ultraviolence comes, when Reacher pulls off the impossible for the tenth time that week, we buy into it because of the commitment to detail.

As before, the storytelling loses its charm when the action moves away from our protagonist. These books always need Reacher’s ex-military mindset front and centre to sell their contrivances.

Even so, you close The Sentinel thinking that the family firm is in decent hands. Good enough, anyway, that I’ll still be a customer for the next one in 12 months time.

Dominic Maxwell is a critic at The Times.

The Sentinel

The insistence by so many Australians that we don’t have a society segregated by class has always been blatantly untrue, and the pandemic has only underlined this. Two new titles from small independent Melbourne press Transit Lounge gaze upon Australia’s social strata.

Tobias McCorkell eyeballs class issues directly in a debut novel set mostly in the once-blue-collar-now-rapidly-gentrifying Melbourne suburb of Coburg. Barry Lee Thompson’s collection of short stories, set in working-class and more comfortable surrounds, is replete with the moody indolence and daily claustrophobia that feels very COVIDesque.

McCorkell’s Everything in its Right Place has us experiencing the world through the eyes and mind of late-teen Ford McCullen, a footy-playing youngster from Coburg who receives a scholarship to a prestigious private school in Toorak, and as such is cursed to hop to-and-fro between two worlds.

On one level, this novel is about family: those we are born tied to, and those who might become our chosen kin. Early on, we learn that Ford is very Tolstoyan about his home life: “We were an unhappy family,” he tells us, though we soon come to understand that this unhappy family is unhappy for most of the same reasons that any family is when under the unending pressure of low generational socio-economic disadvantage.

The not-yet-adult protagonist sees a decades-long lack of money playing havoc with his parents and grandparents, but also learns about the differently-miserable moneyed elite at this new school. “If I’d learned anything in my lifetime other than terror and guilt, it was that money f..ked people up the closer or further away from it they got.”

The novel contains terrific depictions of the beautiful and painful immaturity of young friendships and relationships, including of beautifully naked crushes and other recognisably cringey interactions. Yet Ford’s most interesting relationship is with his father: very strained, and yet he obviously recognises himself most in his dad.

After a lifetime of hurt and abandonment, the son tries desperately to keep his senior at arm’s length: “I could never remember his [house] number — 72 or 79 or 75 — even though I’d been there a million times. I didn’t even know what street he lived on … with Dad, I blocked everything out. I didn’t even keep his phone number in my mobile.”

Generally, Ford struggles to connect with anyone who comes within his orbit. His friends, old and new, cause him to wonder “if such a thing as mateship existed”. And when he wanders past a derelict property in Coburg, he sees “ … a post hammered into the earth and, tethered to it, a goat. The animal was eating up blades of grass as it circled the post, like some sad and tired and very slow lawnmower. I’d never had much affinity with animals, but I understood that goat.”

Although undoubtedly a novel, Everything in its Right Place also reads strangely like a memoir, not only because many readers will be sucked in to believing the author himself lived much of this book, but also because of its form and pacing.

There are seven major parts of the book, each with their own titles, and within these parts the many short chapters each have their own titles, too. It’s what we might call a ‘‘fictionalised memoir’’, which sounds like a synonym for a novel, but it’s not: the structure and feel of McCorkell’s book has more in common with something by David Sedaris, each chapter a piece in its own right.

Narrated in first-person, for some reason the story is told entirely in past tense. It becomes apparent that everything is being relayed by an older Ford looking back, although we never hear directly from this more mature version. This filter is gently placed over all the actions, speech, thoughts and feelings of the teenaged Ford, and it dulls any immediacy and energy.

Thompson’s collection Broken Rules and Other Stories, also his debut, also has many characters exploring adolescence, sexuality, queerness and desire. There’s also the lack of connection with family. As one character says: “They’re not the conversations we have in my family. We don’t hold things up to the light.”

There’s a real autobiographical aspect in this book: stories of boyhood in England and stories of adulthood in Australia, matching the author’s own life. And the pieces are all vaguely interlinked: sometimes with small details, sometimes more in atmosphere.

Thompson’s best work is when he goes very short, when his writing is spare, full of space, echoey. His style is remarkably honed and careful, and sometimes full of great beauty, especially in the more aloof pieces, the ones that are much more mood than plot, reminiscent of the best short fiction by JD Salinger, Amy Hempel, James Salter and Lydia Davis.

Meaning for his characters is often derived from faces and bodies, and narrators are all keen observers, but always at a distance, and full of want, and inevitably also full of regret.

As mentioned, there’s something COVIDesque about this collection: the solitariness of many characters, the long stretches of empty time, the wariness of interacting with others. And people are always falling asleep at all times of day: in cars, in patches of sunny carpet, on soft furniture in the middle of the afternoon.

Yet all the stories were written in a pre-pandemic world, a time when the fictions that govern lives could still be believed. As one of Thompson’s characters says presciently, “Perhaps I’m kidding myself. Probably we’re all kidding ourselves.”

Sam Cooney is a writer and critic.

Everything in its Right Place

Transit Lounge, 288pp, $29.99

Broken Rules and Other Stories

Transit Lounge, 240pp, $29.99