Law & Order creator Dick Wolf joins Netflix’s true crime juggernaut

Dick Wolf’s new series excavates New York’s past, merging storytelling and journalism, unashamedly giving us criminality, violence, gritty realism, horror, and psychopathology. It is riveting TV.

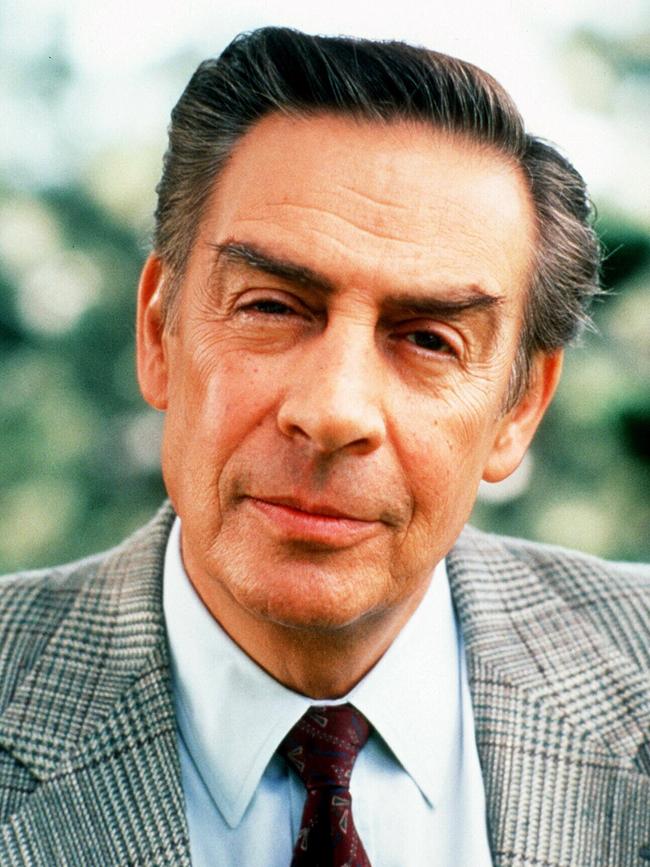

During the pre-streaming era, before Netflix shook up TV-watching conventions, Dick Wolf’s Law & Order was ritual viewing, starting around 1990 and eventually becoming the longest running hour-long prime-time drama series in TV history.

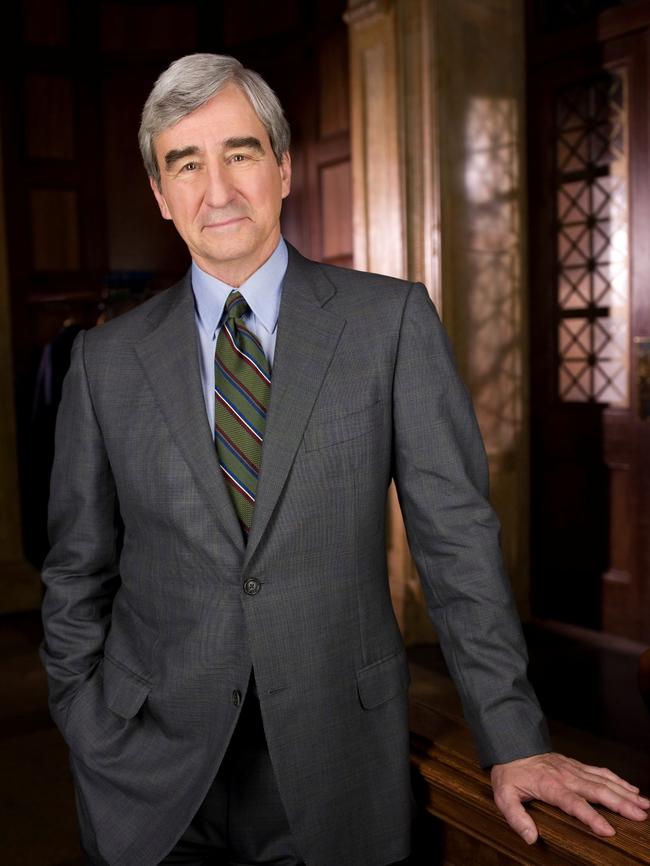

The actors were terrific, their characters enduring favourites, especially Jerry Orbach’s Lennie Briscoe, the quipping master of cop gallows humour and those odd traces of a sad backstory. And Sam Waterson’s Jack McCoy, executive assistant district attorney and then district attorney, who delighted in not only taking on rival lawyers but the system itself, often bending the rules.

There was something about the series’ unique bifurcated format of police procedural and legal drama known for its “ripped-from-the-headlines” stories.

The first half of the drama concentrates on the investigation by the police; the second half follows the prosecution in court by the District Attorney’s office. Wolf, who got his start writing for Hill Street Blues and Miami Vice in the 1980s, liked to say, “The first half of the show is a murder mystery; the second half is a moral mystery”.

And what counted to those of us watching was not so much the apprehension of a suspect by the dogged cops and their eventual conviction, but the discussions about what constitutes a crime in the first place.

Wolf developed a unique genre of noirish visual and thematic richness, one that flourished in a particular moment in US history, tapping into the way that the journey from dead body to resolution in the justice system was riddled with contradictions, difficulties, and compromises. Stand up and open your eyes, he seemed to be saying, and get ready for anything.

As the New York Times said, the show took pains to establish its characters as public servants, not superheroes.

“On the job, the detectives and attorneys wore drab, rumpled suits and worked desk phones from cramped offices. Off the job, they drank and avoided their families, because dealing with predators makes for a harrowing day,” wrote Pete Tosiello, of the way a “a tone of knowing cynicism lent the writing credibility.”

Now Wolf, astute master of the syndication market, with a built-in understanding of how to engage with the multiple sources and directions of influence in TV production, has joined Netflix’s true crime juggernaut with Homicide: New York. The acclaimed master of episodic tonnage now spans streaming as well as network and cable, produced by a loyal team of producers and showrunners, delivering multiple drama series on an unparalleled scale.

It’s Wolf Entertainment’s first docuseries for the streamer, though Wolf is no stranger to true crime with many series, including Prosecuting Evil, Cold Justice and Murder For Hire, on the US Oxygen digital cable and satellite television channel in the US. (He also has nine current procedural series running spanning three franchises, the Chicago and Law & Order shows on US free-to-air TV.) And it’s already a huge hit for Netflix.

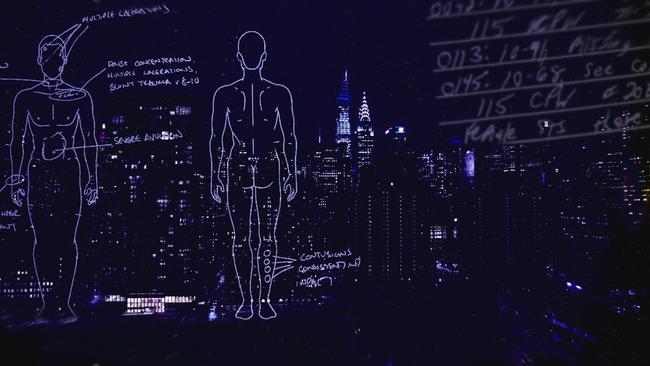

It starts in typical Law & Order style with a terse announcement on printed cards. “On the island of Manhattan there are two detective squads dedicated to homicides: Manhattan North and Manhattan South. They investigate the most brutal and difficult murders. These are their stories.”

Then a New York subway train rushes through the screen in close-up, the camera pushing at speed through its grimy windows, the date 2001 in faded yellow lettering clattering across the image. The camera continues to a framed colourful advertisement inside the carriage. “Visit New York”, it says. And suddenly we are transported through that advertising image to a night-time aerial shot of Manhattan.

There’s an instant sense of a city that’s claustrophobic, expensive and intimidating. But an almost magical place that has an irresistible allure.

The series excavates New York’s past, merging storytelling and journalism, unashamedly giving us criminality, violence, gritty realism, horror, and psychopathology.

There is no apology and no shame, which makes it such riveting TV.

The series artfully juxtaposes visceral archival footage and confronting crime scene photos, enlightening expert interviews, and poignant first-hand narratives from the detectives and examiners intimately connected to these tragedies. And Homicide: New York immersively takes us into crime scenes that have become ingrained in the city’s collective consciousness, stories that are a tantalising blend of fact, fiction and myth.

The focus is less on the murderers that are voyeuristically celebrated in so many true crime shows, and more on the prosaic, painstaking process of investigation. And the terrible guilt and grief felt by the survivors, their friends and relatives, widening the storytelling lens beyond the individual to the collective effect of grief.

The irony of shows like this, something that in Homicide: New York is constantly acknowledged by the police, is that the best stories are the worst stories, narratives of calamity and tragedy.

There are five episodes in this first series, among them the knifing murder of 44-year-old Michael McMorrow by a pair of 15-year-old private school students, dubbed in the media as The Central Park Slaying; the disappearance of Eridania Rodriguez, a 46-year-old cleaning woman, inside a downtown high-rise where she was found bound, gagged and stuffed into the air duct; and the brutal stabbing death in 1996 of high-end coffee shop and office supply entrepreneur Howard Pilmar, found in his office, with no sign of forced entry, no murder weapon, and no signs of a robbery.

The pacing is fast and the dialogue terse. Wolf once described the quality of storytelling in his shows as “no fat writing – writing that tells the story in which each scene flows into the next with the inevitability of falling dominoes’.”

First up is the case labelled the “Carnegie Deli Massacre,” which follows the investigation into the murders of Jennifer Stahl, Charles “Trey” Helliwell, and Stephen King. They were found in Stahl’s sixth floor apartment above the beloved New York institution known for its gargantuan pastrami and corned beef sandwiches, washed down with Dr. Brown’s cream soda, its walls lined with the photographs of Broadway stars.

The bodies of the victims were found bound with duct tape and shot in the back of the head, execution style. Helliwell’s fiancée, Rosemond Dane survived the head wound, as did Anthony Veader, Stahl’s hairdresser, who called 911 after the gunmen fled. Stahl, who sold high-end marijuana from her apartment, decorated with poster-size menus of different brands of weed, was an actor best known as the backup dancer in a blue polka-dot dress in Dirty Dancing.

Who are the men police find on the building’s surveillance tapes; could Stahl’s boyfriend be involved; and why does the name Sean become an important lead in the investigation? The crime haunts the city, unleashing the tabloid columnists. Has New York returned to its bad old days as a broken, ungovernable place, bleak and dangerous and known as “Fear City”?

The episode features NYPD Lieutenant Roger Parrino, a large, burly empathetic man with a dry wit who during the investigation runs foul of the ambitious police commissioner, and Barbara Butcher, the second woman ever hired for the role of Death Investigator in Manhattan, “the body belongs to me” her mantra.

There’s also retired NYPD Det. Irma Rivera, who, as a witness says, looks like she’s stepped straight from the set of NYPD Blue; and the streetwise cop Bill McNeeley, hard-boiled, profane but with an unexpected sentimental streak.

Eccentric Detective Brian MacLeod appears too, never more at home than wearing his earbuds, heavy metal music pulsing as he hunts unceasingly through hours of surveillance footage, concentration never failing.

They are never able to fully distance themselves from the pain of victims and survivors, who feature extensively in interviews. Rivera says she copes with the many deaths having learned to shut her feelings on and off. “I can actually visualise, like a switch in my head, like a light switch, and I can go click, on and off, on and off, and I can shut it on and off.”

While there is Wolf’s usual focus on “Just the facts, Ma’am”, (a quote attributed to Jack Webb’s Joe Friday from 1951’s Dragnet, who brought to TV a level of realism in the police procedural echoed self-consciously by Wolf), the writers also focus on the human qualities of the Manhattan cops, handling them realistically.

They remember vividly, recount the failings of the system at times and their own shortcomings and often somewhat inadvertently swear, still bearing the emotional cost of these investigations. As one of the investigators says, “Every little case takes a piece out of your soul.”

Homicide: New York streaming on Netflix.