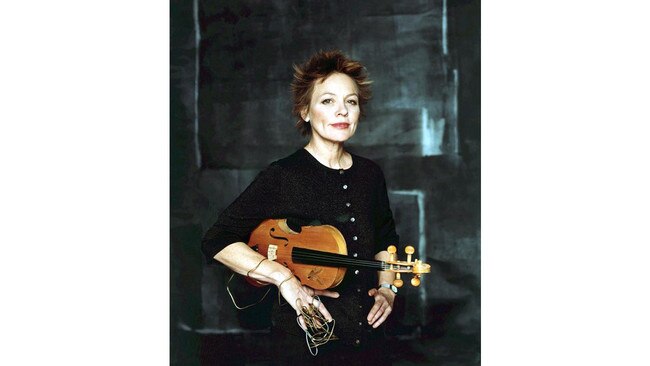

Laurie Anderson on Lou Reed, Home of the Arts, curiosity and freedom

Disdaining formulas, Laurie Anderson loves ‘not knowing what I’m doing’.

One snowy afternoon during her childhood in northeast Illinois, Laurie Anderson was charged with the responsibility of looking after her twin brothers. As she was pushing their stroller across a frozen lake, the ice cracked, and the boys fell in. Thinking quickly, Anderson dived in headfirst, rescued her brothers and ran home to tell her mother what had happened.

“It was a very weird moment, because I was terrified,” she recalls. “I thought: ‘Mum’s gonna kill me, because I almost drowned my brothers.’ Instead, she waited a beat and said: ‘I didn’t know what a wonderful swimmer you were — and what a great diver.’ ”

In hindsight, Anderson thinks of that afternoon as triggering a kind of earthquake whose tremors continue to reverberate deep in her core as a person, and as an artist.

“For a kid who was expecting to have the parent say, ‘What were you thinking about!?’, and for them to say something like that instead, it changes your life,” she says. “I learned at that point, in many ways, the power of language, and that you could literally change someone’s life like that. It certainly changed my life, but it probably changed my work as well.”

When Review connects with Anderson at her studio in New York in early March, this vivid memory occurs to her in response to a question about water, a recurring theme in her work — sometimes consciously, sometimes not.

At her first public performance in the early 1970s, for instance, she played a violin filled with water. More recently, a work named Landfall was first written and performed with San Francisco’s Kronos Quartet in 2013, but not released as an album until February this year.

Most of Landfall’s 30 movements are instrumental, with Anderson providing sparse storytelling atop beautiful arrangements on six of them. Colouring this project was Anderson’s experience of being in New York when Hurricane Sandy struck the east coast of the US in late 2012.

Toward the end of the suite is a movement titled Everything is Floating, where Anderson’s calm voice is accompanied by mournful strings. She says: “And after the storm, I went down to the basement, and everything was floating / Lots of my old keyboards, 30 projectors, props from old performances … And I looked at them floating there, in the shiny, dark water, dissolving / All the things I had carefully saved, all my life / Becoming nothing but junk ...”

When asked about the coincidence between choosing to fill a violin with water for her art, then losing a bunch of instruments to floodwaters, Anderson is tickled by the unseen thread. “The revenge of the violin!” she says with a laugh. “I hadn’t ever made that connection. What an interesting one.”

Later, when talking about the notion of returning to themes in her art, she notes that unconscious inspiration can come from “something that happened to you as a kid that becomes so much a part of you that you don’t even recognise it any more”.

■ ■ ■

In a diverse career spanning more than four decades, Laurie Anderson has cemented herself as a true chameleon of the arts. She revels in the notion of unpredictability, and is as much driven by the idea of surprising herself as she is by surprising the global community of fans and followers attracted to her unique melange of performance art and experimental music.

In 1981, Anderson scored a surprise hit with O Superman, a sparse, eight-minute track built on a mantra-like vocal sample that remains one of the strangest songs to reach No 2 on the British pop charts. With lyrical themes of military arrogance and failure filtered through a vocoder, it was inspired by Massenet’s aria O Souverain, and recorded for $500 that came from an arts grant.

The popularity of that song — which was later covered by David Bowie during his 1997 Earthling tour — led to Anderson suddenly appearing on MTV and in popular music magazines, as well as Warner Bros Records offering her an eight-album deal. Rather than getting caught in the trappings of fame, she chose to treat the experience as an anthropologist would, while also parlaying the attention into a sustainable career, rather than flaming out into obscurity.

In June, Anderson will visit Australia for appearances and installations at the Dark Mofo festival in Tasmania, followed by an artistic residency at the Home of the Arts on the Gold Coast. There, she will perform several pieces, including the world premiere of Stories in the Dark, described as “a collaboration with listeners who use sound to create and destroy their own mental movies”.

When asked if the central thread that runs through her art could be summarised by the word “curiosity”, Anderson replies with a laugh: “That’s a good one because, as you have guessed, I don’t know what I’m doing, and it’s pretty clear. And I love being in that situation. That’s why I do a lot of things. A lot of the work that I’ll be doing at the Gold Coast is things I don’t know how to do as well.”

Does she ever feel as though she is close to exhausting her sense of curiosity? “No,” Anderson replies without hesitation. “I don’t know how to do any of it. I don’t remember how to write a song. I always feel like, every time I try, it’s from a different angle. I never have formulas. I don’t know how to write a story: every time I start, a blank page is terrifying. I really think: ‘How can I think I know how to do this?’ I just enjoy not knowing what I’m doing.”

Hearing her speak these words is strangely liberating and calming. It flips on its head the notion of expertise that we often attach to artists, as once they become known for one thing, we tend to expect that they will continue mining that particular vein.

We pigeonhole individuals as a kind of cognitive shorthand, which is why it can be so jarring to consider the work of someone such as Anderson, who has always flitted from one medium to the next, like a hummingbird enamoured by so many colourful flowers.

“It gives me a sense of adventure,” she continues. “Otherwise, it’s like turning out more identical Coca-Colas, or apple pies. But the pressure — especially in the visual art world — is to get your style, hone your style, repeat your style, sell your style and then never go away from your style. To me, I became an artist because I wanted to be free, not because I wanted to brand myself.”

In this, she sees parallels beyond the world of art. “We get tricked into this thing of having to be consistent,” she says. “Even with our personalities, people say: ‘You’re not yourself.’ So? You want the same person to pop up every time? Why do you need consistency like that? We’re much wilder and weirder than that. Why do you have to always be in character?

“It’s too much like a product. And that’s part of the reason I don’t mind being an amateur. I would rather do something that was experimental than crank out another identical record, or ... ” — here she adopts a masculine tone — “ ‘Hey, that sounds like a Laurie Anderson record!’ ”

Naturally, there are limits to this aspiration; sooner or later, we all find ourselves falling into familiar patterns, no matter how persistent the desire to shake it up.

“Of course, in some ways you can’t escape it,” she says. “In this book I just finished, All the Things I Lost in the Flood, I learned that I keep repeating myself constantly. Sometimes you can call it your themes; sometimes you could call that ‘really repeating yourself’. It’s both. I find that even though you think you’re experimenting, you do go back to things you keep turning over in your mind, thinking: ‘Oh, I wish I could solve that somehow, some day.’ ”

This process of rumination can lead an artist down unexpected paths: from her brothers’ near-drowning, for instance, to her mother’s thoughtful response, to the artistic decision to play a waterlogged violin, to witnessing a natural disaster flooding her basement and turning prized possessions into junk.

The final words Anderson speaks on Landfall to conclude the track Everything is Floating are ones that perfectly capture her ability to view experiences through two artistic lenses simultaneously: “And I thought: ‘How beautiful. How magic — and how catastrophic.’ ”

■ ■ ■

Anderson performed Landfall with the Kronos Quartet in Australia in early 2013, at the Adelaide Festival and the Perth International Arts Festival. “We were still working things out,” she says. “I was very nervous about going there, because Lou was very sick at that time and I almost cancelled going because I thought I really should not be that far away. My main memory of that was feeling like I had to get back as soon as I could.”

The man she speaks of is Lou Reed, the singer and songwriter who came to prominence while fronting rock band the Velvet Underground in the 1960s, and who enjoyed a prolific and prosperous career in the following five decades under various guises, both solo and collaborative. Anderson met Reed in Munich in 1992, and from then on “we tangled our minds and hearts together”, as she has described their shared lives.

The pair curated Sydney’s Vivid Live in 2010; Reed performed with his noise group Metal Machine Trio, while that Sydney visit also marked the first occasion on which Anderson performed an unusual work that will soon get a repeat airing on the Gold Coast.

It’s called Concert for Dogs, and footage published online shows Reed wearing his ever-present black sunglasses and sitting by the sound desk in the middle of a hundreds-strong crowd of people and canines at the Opera House steps, listening to music played at low, dog-friendly frequencies.

Reed died of liver cancer in October 2013, aged 71, but his presence remains a strong influence in Anderson’s life. As Kronos Quartet leader David Harrington recalled in a recent interview: “We were rehearsing [Landfall] at the University of Maryland and Lou called out: ‘Laurie, this is f..king beautiful, don’t change a note.’ I think in so many ways this piece is for him.”

Two weeks after his death, Rolling Stone magazine published an extraordinary piece of writing by Anderson in which she reflected on their relationship and the experience of watching her partner die. “His eyes were wide open,” she wrote. “I was holding in my arms the person I loved the most in the world, and talking to him as he died. His heart stopped. He wasn’t afraid. I had gotten to walk with him to the end of the world. Life — so beautiful, painful and dazzling — does not get better than that.”

In that beautiful piece, she paraphrased songwriter Willie Nelson, who suggested that 90 per cent of the people in the world end up with the wrong person, “and that’s what makes the jukebox spin”.

What, then, makes Anderson’s jukebox spin today? “I think love does,” she says. “By that I mean trying to be open to things, and not just judgmental and afraid. Here’s the thing: when you lose your partner and a conversation that’s decades long stops, it is a disaster. There’s no way around it. But it also opens you, and you suddenly realise: all we have is this moment. And so you recognise how transitory this life is.

“It’s a mind-blowing experience. That door does not open for many people, so when it does, walk through it. For me, it was a real wild experience, and continues to be. It’s not like it stopped being surprising; it shocks me every day, how people and things apparate. I try to look at that, recognise it and express it, and love it. That’s what makes it spin for me.”

And then Anderson apologises for ending the conversation a little earlier than planned, as there are a half-dozen people in her studio in New York waiting for her to hang up the phone. The occasion? A small party to celebrate the 76th birthday of her Lou.

Laurie Anderson will appear at the Dark Mofo festival in Hobart on June 13, and as artist-in-residence at Home of the Arts, Surfers Paradise, from June 20 to 24.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout