Kristina Olsson’s Shell relates how vision and war shape 60s Sydney

The fundamental astonishment of Kristina Olsson’s novel Shell is that no one thought of doing it before.

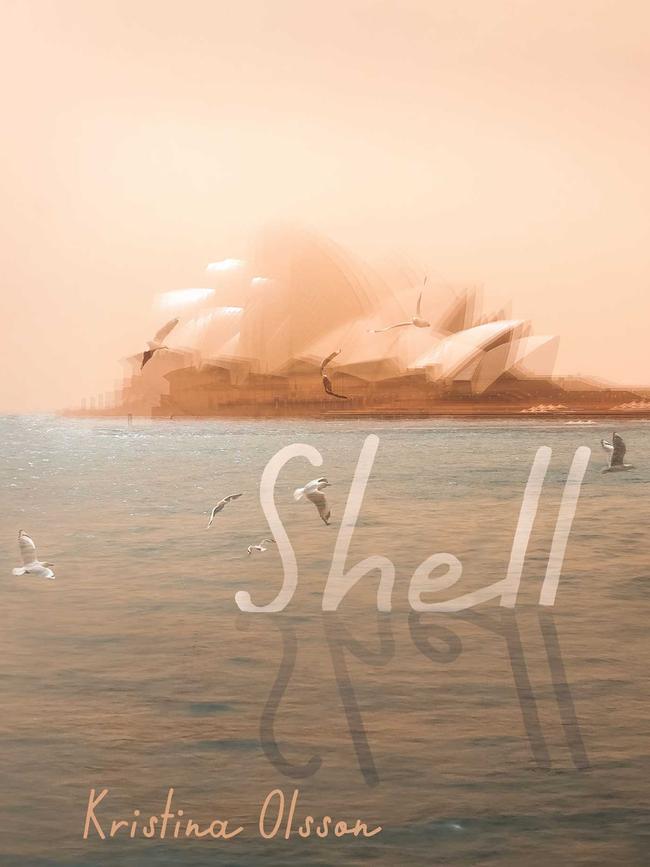

The fundamental astonishment of Kristina Olsson’s novel Shell is that no one thought of doing it before. The story of the construction of the Sydney Opera House, undeniably one of the 20th century’s great buildings, is one fraught with paradoxes and rich with wider context. It constitutes an epic of cultural malfeasance, one that begs for creative interrogation.

The regrettable truth of the Opera House is that we didn’t deserve the gift we were given. We sullied the legacy of the man who envisaged it and we made a point of forgetting the injury we caused him afterwards. But it was not just a building that we deformed by dint of political infighting, constitutional vulgarity and sheer bloody-mindedness.

This sorry tale of a visionary structure and its architect, Jorn Utzon — a man who never returned to Australia after being forced out of the project he initiated — speaks to larger idiocies, to a failure of imagination we have yet to expunge from our national make-up.

Olsson takes this history and runs hard with it in fictional terms. She locates the drama surrounding the building and embeds it in a historical moment: the point where an obtuse and self-satisfied political class decided to feed its young men into the geopolitical ferment of conflict in Southeast Asia, against the advice of its defence department and with little encouragement from the South Vietnamese government, with predictable consequences.

The primary achievement of the novel, the first from Scribner’s new local literary imprint, is to do what superior historical fiction is meant to do: ground large abstract forces in a distinct milieu, using psychologically plausible characters as opposed to editorialising ciphers, while using prose that captures and honours individual lives, those human eddies caught in the broader historical flow.

Foremost among these is Pearl, a journalist who, despite being a young woman from a troubled background, has won her way into the boys’ club of The Telegraph, with its dusty, ink-stained offices, albeit at the cost of separation from her two brothers, whom she hasn’t seen or spoken to in years but whose continuing existence is reinforced by the news, relayed by a political contact, that the Menzies government is set to significantly expand military conscription for Vietnam.

We initially meet her for a mere two paragraphs in 1960, when she stands and weeps alongside other journalists and onlookers on the day that Paul Robeson, the singer and political radical, performs for the workingmen whose job it is to realise Utzon’s architectural plans. For Pearl, what Robeson performs that day is a kind of sanctification: ‘‘This is what she will remember: he turned the air holy.” Olsson pictures the sweat-slicked workingmen dropping their heads as if receiving benediction.

The momentary grandeur and rightness of this image is just that, momentary. The narrative proper begins half a decade later, in 1965, as Australian involvement in Vietnam looms and the progressive elements of the younger generation begin to find the mood of the moment shifting against them.

We follow Pearl through smoky cafe arguments with journos and fellow anti-conscription activists, track her across the city and its harbour, and meet the small cast of eccentrics, lovers and battlers who constitute her alternative family. As a picture of Sydney in that era, Brisbane-based Olsson has done a marvellous job. The city is built from a hundred stray touches, a pointillist accretion of detail.

Mainly we learn that Pearl emerges out of tragedy. A mother who died early, a grieving father who drank himself out of the picture, and two younger brothers she neglected to take on as a replacement parent, busy as she was establishing her own life and career.

The guilt she feels at this self-identified dereliction of familial duty is irradiated by the possibility that they will be sent to war without her ever finding them again. So it is that she begins searching again in earnest.

The other half of the narrative is given over to Axel, a young ceramicist from northern Sweden who has come to Sydney to work on interior additions to the Opera House at Utzon’s request. Axel idealises both architect and building, even though he has arrived too late to work directly with the man, who has largely retreated to his Pittwater home after coming into conflict with the project’s engineers and the state’s politicians.

When Axel and Pearl meet, it is this shared love for the building that first binds them. It stands for human possibility beyond the pettiness and violence of the moment. For Axel, indeed, it holds an almost religious charge:

Now, though he had been working at the site for a month, though he’d walked the same path to it every day, it still took him by surprise: the tremor of emotion as he rounded the quay and saw the sails arcing out of chaos. As if he’d come upon a rare and beautiful animal in a stark landscape. There was no Swedish word to describe this, no English word that he knew; it wasn’t as simple as ‘‘awe’’ or even ‘‘love’’. It was the clutch at his heart as he lifted his eyes to its curves and lines. Its reach for beauty, a connection between the human and the sublime.

Though the novel resolves itself into an engaging drama of conscience, one in which the failure of the Opera House to be realised as it should have been fits cleanly with certain miscarriages in the nation’s social and political order, it is this passionate noticing that constitutes the main claim to our attention.

Those who prefer their stories served straight up may be frustrated by the poetic indirection of the prose. But those who share the sense of Sydney Harbour as a perfect stage for human action — who adore its signal landmark while pondering what might have been — this is a novel with a sharp eye, a warm heart and sprawling ambitions, painted on the most splendid canvas of all.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Shell

By Kristina Olsson

Simon & Schuster Australia, 384pp, $35 (HB)