Kissinger: Niall Ferguson biography sets the stage for statesmanship

Henry Kissinger’s authorised biographer, Niall Ferguson, has produced a masterpiece he expects to be savaged.

If your aspiration was to become an historian, you could hardly conceive of a better trajectory than that of Niall Ferguson: Glasgow Academy, Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, the London School of Economics, the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, 15 books, television documentaries, trenchant public commentary and now a biography of Henry Kissinger. It is an astounding record for a man still only 51.

This first volume, Kissinger 1923-1968: The Idealist, is masterful. It exhibits a maturity of expression and judgment that is immensely impressive. It points irresistibly to the forthcoming second volume as perhaps Ferguson’s crowning achievement.

He was only 40 when Henry Kissinger approached him, in 2004, and asked if he would write an authorised biography. It was a remarkable tribute to the young historian that an elder statesman twice his age should make this request. Kissinger must have been impressed by Ferguson’s body of work over the preceding decade, starting in 1995 with Paper and Iron: Hamburg Business and German Politics in the Era of Inflation, 1897-1927, and concluding in 2004 with Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire.

Ferguson already had many other projects on the drawing board and knew a biography of Kissinger would not only be a massive undertaking but, as he writes in the introduction, ‘‘would inevitably be savaged by Christopher Hitchens and others’’. And so, in early March 2004, ‘‘after several meetings, telephone calls and letters, I said no’’.

This, he comments wryly, ‘‘was to be my introduction to the diplomacy of Henry Kissinger’’, who wrote to him exclaiming it was a pity he had declined, because 145 boxes containing his private papers going back ‘‘at least to 1955 and probably to 1950’’, which he had believed lost, had turned up; and also because ‘‘our conversations had given me the confidence — after admittedly some hesitation — that you would have done a definitive — if not necessarily positive — evaluation’’. Seduced by the allure of those papers, Ferguson consented.

The book is impressive in at least seven distinct ways: its mastery of a mass of detail; its architectonic balance; its felicity of expression; its often striking and elegant obiter dicta about human experience, academic life and world affairs; its insightful and unflinching character sketches of successive American presidents and other prominent figures, as well of numerous other characters in the extraordinary story of Kissinger’s first 45 years; its uniquely original and strikingly independent assessment of Kissinger’s character and development; and its magnificent stage setting for what is to come in the second volume, which will examine Kissinger as national security adviser and secretary of state.

Ferguson’s sweeping works and outspoken stances as a public intellectual have drawn fire from both the political Left and academic or journalistic writers who find fault with his outlook or his work. Among those who have claimed to find fault with this book, Greg Grandin, writing in The Guardian in mid-October, typifies just the kind of tendentious ‘‘savaging’’ that Ferguson anticipated would come from Hitchens and others.

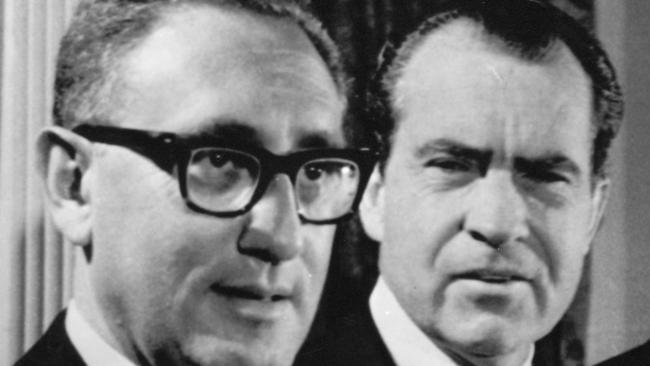

Grandin, whose own book, Kissinger’s Shadow, is due out soon, asserts that Ferguson’s book is an extended but litigious, lazy and ‘‘boring’’ defence of its subject. He insists Ferguson has avoided the ‘‘dark side of Kissinger’s character and motivation and is in error — deliberately and culpably — in rejecting the claim that Kissinger helped Richard Nixon sabotage the secret negotiations with North Vietnam in Paris in 1968, in order to secure his appointment as Nixon’s national security adviser.

Grandin plainly has the same view of Kissinger as Hitchens set out in The Trial of Henry Kissinger: that he was a war criminal on a large scale and should be hanged for decisions that he actually or allegedly took while in office, regarding Indo-China, Bangladesh, Chile and East Timor, among other matters. But Grandin is jumping the gun. Ferguson argues, very persuasively in my view, that Kissinger was motivated not by ‘‘dark’’ impulses but by a highly intelligent, complex and perceptive commitment to statecraft and to finding ways to make American foreign and international security policy work better. He demonstrates meticulously that Kissinger did not sabotage the Johnson administration or connive in any malign way with Nixon, and that he did not expect to become national security adviser at all, right up to the point when Nixon explicitly made him the offer in December 1968. He depends on no convoluted or tendentious reasoning but on a detailed and judicious assessment of the roles of many actors in the events leading up to the December 1968 appointment.

Determined to assert that Ferguson is out to exculpate Kissinger in volume two, Grandin appears not to have read most of volume one. In fact, Ferguson’s long, deeply informed account of Kissinger’s intellectual formation and his disillusionment with the Johnson administration’s war in Vietnam as early as 1965 make compelling reading. One of the most eye-opening revelations is that criticisms of Johnson’s policies, of the workings of his national security decision-making apparatus and of the conduct of the war in Vietnam that have always been associated with left-wing critics of the war and, in my opinion, with the thinking of Daniel Ellsberg before and after he leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times , can be found explicitly in papers and memorandums written by Kissinger in 1965-66.

This is all the more striking because, at least in this volume, Ferguson hardly mentions Ellsberg and certainly shows no sign of having set out to argue that Kissinger anticipated Ellsberg’s Papers on the War or more general public stance after 1971. Yet the precise wording used by Kissinger in a series of papers in the mid-1960s is so redolent of things Ellsberg wrote years later that I found myself wondering whether Ellsberg had unconsciously echoed Kissinger, whom he knew from Harvard.

The difference between the two, after 1968, was that Ellsberg defected from the inner councils of state and sought to change policy by leaking vast quantities of classified documents to the press. Kissinger sought to reshape the inner workings of those councils through his highly intelligent and quite transparent writings up to late 1968, and to take direct responsibility for their workings when offered the chance by Nixon, despite never having liked Nixon as either a person or a politician.

Central to the architecture of Ferguson’s biography is his attempt to trace the development of Kissinger’s thinking over decades. Grandin asserts that this makes Kissinger ‘‘boring’’. He could not be more mistaken. What is boring are the tired old cliches of the Left about Kissinger. In this new biography we can see Kissinger’s gifted mind, his ideals, his use of history, his relationships with mentors, his analytical acumen, his political outlook and his attempts as an immigrant German Jew to grasp and then shape the machinery of foreign and security policymaking in the US. The book concludes with a very fine summation, in the 14-page epilogue, of what Ferguson calls the bildungsroman of Kissinger — ‘‘the tale of his education through experience, some of it bitter’’.

This epilogue is in itself a beautiful piece of writing, opening with a reference to Goethe’s famous bildungsroman Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship and concluding with an invocation of the fifth century BC anti-war comedy Peace by the Athenian playwright Aristophanes. It is a measure of the quality of Ferguson’s mind that he has been able to avoid looking at the early life of Kissinger through the jaundiced lenses the Left would have had him wear; to examine the subject dispassionately; to have appreciated both the ironies in Kissinger’s circuitous ascent to the West Wing of the White House and the acute dilemmas that lay in wait for him as a scholar-statesman.

As he remarks, Kissinger worked, throughout the 60s, for Nelson Rockefeller, whose aristocratic liberal Republicanism he admired, despite the fact that Rockefeller was never going to become president; then was recommended to Nixon by both Rockefeller and Johnson. What he took on had already driven the Democrats, both liberal and conservative, to despair. He could have left it to others. He chose to take the poisoned chalice and attempt to deal intelligently with the vast challenges confronting the US by the end of 1968.

What followed made him one of the towering figures of 20th century statecraft. Reading the second volume of Ferguson’s biography will, therefore, be immensely absorbing. But make no mistake, in this first volume he has produced a masterpiece and one that must be read in every graduate school of international relations, history and statecraft.

Paul Monk has a PhD in international relations and is a former senior intelligence analyst. His latest book is Opinions and Reflections.

Kissinger: Volume One: The Idealist

By Niall Ferguson

Allen Lane, 656pp, $79.99 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout