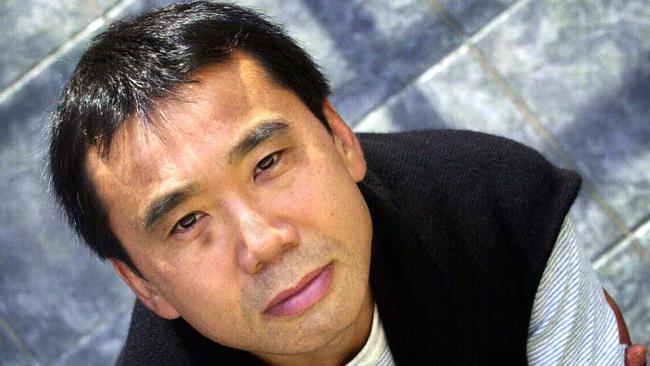

Killing Commendatore by Haruki Murakami: the artist transformed

No amount of narrative outline can clarify the oddity that is encoded in Haruki Murakami’s latest offering.

Alberto Giacometti painted portraits the way a grieving person clings to the image of a loved one who has died. Every neuron strains to recall and imprint the features of the lost figure, even as their face grows indistinct over time. The paradox of such images is that they become more concentrated as they grow less concrete: the drive to recapture intensifies as living presence recedes.

For Giacometti, the act of memoration through art became more important as friends and family were touched by the violence of World War II. His art admitted that the line that held him to those he knew and cared for had narrowed to a pencil stroke. The haunting power of his late biomorphic statues and paintings emerges from the concentration that attends this awareness. Their gravity is greatest at the point where they threaten to disappear entirely.

Harumi Murakami’s new novel, which coincidently opens with a prologue in which a portraitist is challenged to capture the likeness of a man without a face, triumphantly deploys a kindred method.

It explores the demarcation between dream and reality, alienation and connection, presence and absence, weird past and banal modernity, in a manner calmer and more gravely constrained than the fantastic theme park of its giant predecessor 1Q84, and it is all the more powerful for doing so.

Those who know their Murakami will be as familiar with the set-up as a filmgoer at a new Bond movie. A mild, nameless, constitutionally solitary man in his mid-30s is abandoned by his wife, without preamble or explanation, over their kitchen table one lunchtime. He immediately leaves their flat in the Tokyo suburbs and spends the following months driving along remote corners of Hokkaido and the country’s northeast in a battered Peugeot, a road trip dripping with existential anomie.

He is a portrait painter of some talent who has fallen into the role after harbouring early ambitions as an artist. These days he makes decent money flattering captains of industry for a fee. Yet even this impulse leaves him in the months after his marriage’s abrupt failure.

Through the offices of an old friend, he eventually finds a house in an out-of-the-way mountain district — it belongs to an elderly artist of conservative aesthetic bent and considerable repute now institutionalised with dementia — and settles into a quiet life: teaching students at the local art college, pursuing desultory affairs with two of his mature students, listening to the large collection of opera LPs left behind by the senior painter, and signally failing to paint a thing.

All of this changes when the owner of a large mansion nearby offers the narrator a hefty amount to take on one more portrait commission. The urbane, well-heeled businessman whose name, Menshiki, means “avoidance of colour’’ has a perfectly groomed head of white hair and a mysterious past. The portraitist, who relies on some human connection with his subjects to shape his work, initially fails to gain purchase: Mr Menshiki’s personality and motivations are too opaque.

Then, one night, the painter wakes to the sound of a bell being rung somewhere close to the house. A search reveals the source of sound emerging from beneath a pile of rocks in the woods. This eerie event, which recurs over following nights, is an irruption of strangeness into what has so far been a resolutely ordinary account of midlife malaise, and it is one that draws the portrait painter and his subject into greater intimacy, as together they investigate the phenomenon.

From this point onwards, the novel is more obedient to the dream logic that usually drives Murakami narratives. There is the discovery of a mysterious picture, a lost masterpiece in the traditional Japanese style by the former owner of the house, whose unveiling after many years hidden in the attic seems to awaken whatever spirit it is that occupies the pit the two men find hidden beneath the rock.

The link becomes explicit when that spirit appears to the painter in the form of a 60cm-high figure from the painting — a mini-me version of the commendatore whose violent death is the subject of that work. The creature claims to be pure idea made manifest, but it also gives dark hints of dangers that lurk around the astonished artist.

And there remains the enigmatic figure of Mr Menshiki: charming, able, driven — and moved by a love that cannot be realised. His role in the novel increasingly recalls that of Jay Gatsby — a Gatsby who plots in grand solitude rather than among a hard-drinking throng of hangers-on. Menshiki’s plans are also moved by a “colossal vitality’’ that cannot help but exceed the worth of its object.

No amount of narrative outline can clarify the oddity that is encoded in Killing Commendatore’s DNA, however. Rather than work as Giacometti did, paring back to achieve the appearance of mass using space and line, Murakami ensures that the most orderly, clear and realistic attentions are devoted to those aspects of the novel that are most bizarre. The effect is to wield novelistic realism in such a way that it begins to critique realism’s status as a depiction of the way things really are.

It is here that a story about an artist rediscovering his power as a creative agent (and Murakami’s depictions of the artist at work are some of the best pages here) begins to combine with certain philosophical questions.

As the painter returns to his calling, initially through his breakthrough portrait of Mr Menshiki and then through a small suite of pictures that tantalise and threaten to solve the mysteries the narrative throws up, the idea of romantic agency — of the artist creating and remaking the world from scratch through sheer force of will and imagination — bumps up against another, older idea: that of the artist as a medium through which inchoate forms and ideas are made manifest.

“The best ideas are thoughts that appear, unbidden, from out of the dark,” says Menshiki as he admires his portrait:

It’s like an earthquake deep under the sea. In an unseen world, a place where light doesn’t reach, in the realm of the unconscious. In other words, a major transformation is taking place. It reaches the surface, where it sets off a series of reactions and eventually takes form where we can see it with our own eyes.

And this, given Murakami’s stated creative method in interviews and essays, is as close to a description of the Japanese novelist’s aesthetic as any other passage from his body of work. The author claims not to dream at night, since he spends his days in the waking dream of literary effort.

Dreams, though, are hard to make work on the page. As the artist thinks to himself after his subconscious goes into overdrive during a brief nap, each “fragment has a certain gravitas, but by intertwining they cancelled each other out”. True enough: where dream logic can make a short poem or a film work marvellously, the way words are anchored to meaning, and the way narrative is impelled by a logical series of words chained together, dreams can be exposed as cleverly orchestrated nonsense.

Murakami’s career has not been entirely free of moments where narrative collapses under accumulated improbability. But in these pages a silken thread of true feeling is held by the artist and his most significant subject, Mr Menshiki. Both men have lost close family, or have failed to connect with them altogether, because of some past tragedy or present psychological block.

“The two of us were motivated not by what we had got hold of, or were trying to get,’’ the artist acknowledges, “but by what we’d lost, what we did not now have.”

Killing Commendatore feels like a summation of themes that Murakami, as a creative writer and a translator, has spent a career exploring. Just as 19th-century Russians took the French and English novels of the day and wrenched them into strange new territory (spiritual and geographic), so too has Murakami taken 20th-century existentialist thought, whether the novels of Camus or the hard-boiled noir of Raymond Chandler, and given it a distinctly new and strange inflection.

In this novel, a form of Zen existentialism is espoused: not with any faith that nirvana may eventually be achieved, but nonetheless proceeding with a faith that art can serve as a gesture of decency and fellow feeling for all those other selves imprisoned by an essential loneliness in a world that appears to lack meaning. Killing Commendatore insists that our most meaningless dreams nonetheless should be treated as meaningful, in defiance of implacable reality.

And its intermittent weirdness, intellectual questing and expansive narrative architecture eventually dissolves into a story at once movingly human and plainly told.

It is a novel that should recall us to the fact that one of Giacometti’s late, great muses was a Japanese professor of philosophy, Isaku Yanaihara. The first translator of a number of seminal texts of existentialist philosophy and literature, Yanaihara was one of those rare figures capable of keeping perfectly still for those long hours the Swiss artist demanded of his sitters. Giacometti said of the portrait that resulted: “We used to work all day, and by the evening, it was a painting. And the more it worked out, the more he disappeared.’’

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Killing Commendatore

By Haruki Murakami

Harvill Secker, 704pp, $45 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout