Killer instinct for gripping narrative

Filmmaker Skye Borgman turns her forensic gaze to a case of patricide in Netflix’s I Just Killed My Dad — the extraordinary story of teenager Anthony Templet.

Skye Borgman seems to be everywhere on Netflix at the moment. She runs production company Top Knot and as director and cinematographer she has shot more than 50 films, both narrative and documentary. Her subjects include, according to her bio, “rock stars, prime ministers, drug addicts, environmentalists, Academy Award winners, Buddhist nuns and anarchist chocolate-makers”.

Her films include Mumia: Long Distance Revolutionary, which chronicles the life of the former death row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal; We Are Galapagos, an intimate portrait of the people of the Galapagos; and Dead Asleep, which looks at whether Randy Herman Jr murdered his flatmate and childhood friend while he was sleepwalking.

Now Borgman has become a force in the burgeoning true crime genre, a prominent documentarian with several trending films and streaming series and causing gasps of astonishment: stories of desire, sexual and mental cruelty, deceit, faith and forgiveness. And murder.

Her stories reach vast audiences and include Abducted in Plain Sight, the true story of a girl who was kidnapped – not once, but twice – by the same person with whom her parents were friends and fellow church-goers. Girl in the Picture uncovers the weird web of mysteries surrounding the alleged hit-and-run death of a 20-year-old woman named Tonya Hughes, a dancer at a strip club in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The film received 11 awards on the international festival circuit before becoming a trending sensation for Netflix.

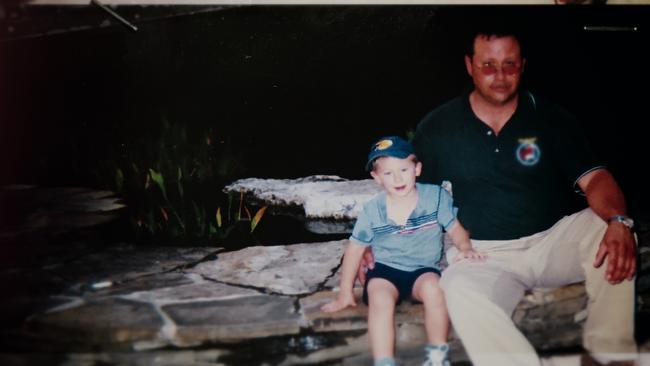

Her latest, I Just Killed My Dad, is the extraordinary story of Anthony Templet, a teenage boy who one dark night in Louisiana’s Baton Rouge shot his father with a heavy calibre hand gun, one of two he owned, and patiently waited for the police to come. Did he shoot his father Burt in an act of self-defence or was something more malevolent involved?

“I’m drawn to the ones I just don’t understand,” Borgman says of her recent shows, all directed with close-up intimacy and a subjective empathetic eye, as she tries to understand her cases on both the level of individual choices and cultural forces. “You know, that have some element that I just can’t quite comprehend, and that really is what’s so interesting and fascinating to me, is to be able to come into a project, and learn more about it, and the ability to have my mind changed or to have my approach altered – or just to be able to look at the world in a more complete way.”

Borgman looks for the “unbelievable” elements in stories as she questions and tries to figure out just what else she might discover behind these traumatic mysteries. As a consequence, she spends a lot of time with the darker parts of humanity. “Usually when it’s something that’s truly unbelievable, there’s something that sort of runs parallel to it that can sort of explain it, or at least give you greater insight into it – and finding those parallels is really, really interesting.”

Aware that true crime is increasingly a difficult and thorny cinematic practice, her abiding preoccupation now as a filmmaker is a quest for truth. “I want to have my eyes opened, I want to have connections strengthened, I want to have more than just a film experience.”

The first episode of I Just Killed My Dad, I’m Not a Killer, begins with an empty chair in a cavernous backlit warehouse space. We hear footsteps and a young man appears and sits. He’s identified as 18-year-old Anthony Templet. A voice off-camera asks, “Why do you think it’s important to tell your story?” He peers through his spectacles and leans forward slightly. “Well, it’s important because my life is on the line and I’m innocent and I want people to know I’m not crazy, not a murderer and I’m innocent.”

His voice is flat, monotonous, his eyes empty of life. There is an abrupt audio cut to the 911 call that begins this terrible mystery with then 17-year-old Anthony saying simply: “I just killed my dad.”

What follows is the gradual unfolding of a tragic story. Borgman interweaves interviews with many of the surviving parties involved, family friends, relatives, police and judicial officials, news footage from TV stations, home video from Anthony’s house and alarming CCTV footage. There are also crime scene photos, some video taken by police and by paramedics, and reconstructions of the murder and of the police apprehending Anthony in the street.

The house itself is constantly referenced in ghostly tracking shots, adding to the slightly gothic quality of the story. And spectral aerial shots of Baton Rouge and the various locations that feature are used to establish context and add to the noirish style of Borgman’s presentation. This adds the right kind of visual structure and cinematic depth to her storytelling, largely based on the many interviews.

Borgman has a great feel for narrative and while the process here is relatively conventional there are many details to place in the timeline and many characters to establish within the story. And she slowly builds the emotional arc of the narrative, too, after establishing so vividly the shock of the shooting. She works like an investigator in a psychological mystery – think of the novels of Jonathan Kellerman – as she looks for a chain of evidence and works backwards to discover what really happened.

We quickly learn Burt Templet was known as “that strange figure” in the neighbourhood, often seen drunk, abusive and unpredictable, his home surrounded with CCTV cameras. And that when it came to that house and his relationship with his son, he was a controlling, manipulative man who kept Anthony out of his school, isolated him from other family members, tracked Anthony’s every movement and abused him. “He always found a way to make me feel I was doing something wrong,” the boy says.

We learn that he rarely stepped outside the house, didn’t know his mother’s name, had no idea who Tom Hanks or Tom Cruise were, and the concept of a high five was a complete mystery. Suddenly Anthony seems like a boy who somehow slipped through the cracks, unnoticed by the world as he lived in sadness.

We are also introduced to the man who becomes his defence attorney, Jarrett Ambeau, a Louisiana boy, he says, who has survived a thousand bar fights, but who is highly intelligent and accomplished. He’s almost too mythic to be real, a lawyer with a deeply held moral code, the law to him often an impediment to true justice.

He acts pro bono for Anthony, recognising something of himself in the boy. The lawyer, who is presented like a hard-boiled character from a Michael Connelly novel, calls his parents hippies and describes an unstable upbringing where he often witnessed drug deals and abuse: a childhood of trauma, different but not unlike Anthony’s. “I embrace that part of me that’s a little crazy, a little out of the box,” he says, but his early days have nurtured an ability to get things done.

“The fascination with murder and illegality is a perennial one, because the shock of the deed creates a schism between order and chaos,” Sarah Weinman writes in her introduction to Unspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit and Obsession. “We wish for justice, but even when we get it, the results are somewhat hollow. We gorge on facts and innuendo but are then left with the hangover of trauma, the aftermath of a system that too often fails people.”

Borgman in her work seems implicitly aware of this: the way that, as Weinman says, we crave a narrative that restores a sense of righteousness but which leaves us with scraps of barely connected meaning. She wants her viewers to attempt to find ways to better understand these connections.

“I want that conversation to continue once the credits roll,” she says, discussing her film Dead Asleep, about the man who claimed he killed his roommate while sleepwalking.

“I don’t necessarily want to be working on projects where at the end of it you go, ‘Great, OK, all done’. I know what happened and I turn and walk away and the conversation doesn’t continue … I want that conversation to continue because I think that’s where documentaries have a lot of power.”

I Just Killed My Dad, streaming on Netflix.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout