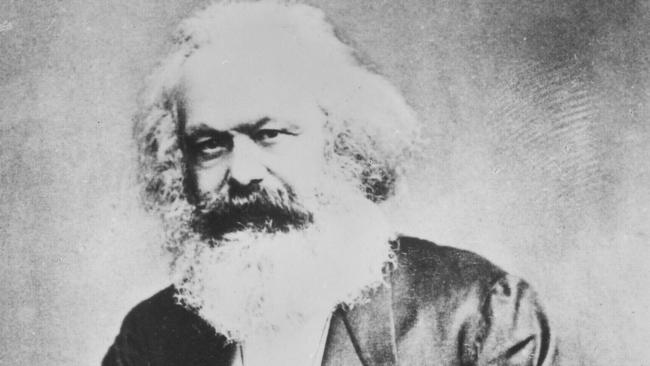

Karl Marx, Greatness and Illusion: not a soviet, more a philosopher

History identifies Karl Marx with Soviet Communism, but the truth is he had little to do with it.

Who was Karl Marx? Easy. He was the guy who caused the Russian Revolution, right? Big guy, grumpy, beard. No, sorry, that was Vladimir Lenin, different time and place. Bald guy, professional revolutionary.

Marx died in England in 1883. Lenin then was still in shorts, and in a rather different part of the world. Revolutionary 1917 was a world away. And perhaps there were some other, more material than ideological, issues involved in the Russian Revolution as well. This was not just a matter of ideas or ideology. Ideas matter, but they do not change the world themselves.

The irony of history is that Marx would come to be identified with Soviet communism. This identification proved to be fatal in more ways than one. As the liberal father of sociology, Max Weber, wrote to his friend, the young Hungarian hothead Georg Lukacs, the Russian Revolution would set the cause of socialism back by 100 years.

Time’s up, end of this year. The process looks like taking even longer. How, in the meantime, to unhook these moments, times and places? Who was Marx, disinterred out from under the dead weight of the Russian Revolution?

British historian Gareth Stedman Jones has been working on this big book for a long time. The result, as George Steiner put it in The Times Literary Supplement, is no friend to elegance. But it is an astonishing achievement, even if the result is overwhelming. This book is so big that it is hard to read without getting sore wrists.

Stedman Jones seeks to develop an approach that makes the book freestanding, so that at any given point you do not need to head to the bookshelf or to Wikipedia to keep up with the narrative. The devil of the book is in its detail. This is not a text that can be criticised for omission. Stedman Jones sets out to relocate Marx, if not to replace him. The nuance of his life and times is dealt with in detail and with finesse, attention duly paid to text and context.

Texts matter, as the Bolsheviks did not know many of them, and made Marx up in their own image. As Stedman Jones observes, for example, Marx refers twice in passing to the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat; Lenin turns it into a core principle of Marxism. Marx uses the word party to refer to his handful of followers; Lenin turns this into the combat, or vanguard, party of disciplined revolutionaries.

Context matters, as the story of Marx is also, in Stedman Jones’s telling, well distant, long gone. Marx’s world is different to Lenin’s, which is different to ours. More, Marx became stuck in the vision of his own youth. He was also, as Zygmunt Bauman used to say, a youthful hothead from the Rhine.

The core thesis of the book here is that Marx takes on an apocalyptic world-view in the 1840s and fails to revise it as the world of capitalism and liberal reform changes in the second half of the century. Whatever this world is, it is before Bolshevism, before 1917.

The young Marx is a romantic, a poet; maybe he should have stayed there. Later he is a journalist and, as Stedman Jones observes, it is his columns for the New York Daily Tribune that are the most influential of his work in his own time; maybe he should have stuck with journalism. In between times he was a philosopher, but this was the least of his impact.

During most of his lifetime, his followers could be counted on fingers and toes, though his enemies were apparently more numerous.

Stedman Jones covers all this beautifully. Family, religion, philosophy, money, poverty, friends, enemies, Friedrich Engels, health, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, exile, housing, character, Paris, London, Manchester, Shakespeare, tippling, it is all there.

Most of all, there are Marx’s ghosts, Bourgeoisie and Proletariat, the class actors who become locked into his choreography.

Stedman Jones has written in the past about the language of class. His argument is not that class does not matter, but that Marx conjured up his own class actors from the revolutionary period of his youth.

By the time of Das Kapital, however, the working class was busy doing other things, organising for reform, picking up the consumption side of the Industrial Revolution, looking to its gains and not only its losses.

In this telling of the story Marx is put back in his box, the one marked German Philosopher, 19th Century. This is an approach pioneered by Leszek Kolakowski, whose views on Marx began with the observation that ‘‘Karl Marx was a German philosopher’’. It is a useful corrective to the Bolshevik appropriation, which turns Marx into Lenin or else engages in the lazy play of Russian dolls.

This telling of the story sidesteps the 1960s and the rediscovery of Marx as the advocate of freedom and emancipation. It is silent on the contemporary rediscovery of Marx by French economist and author Thomas Piketty and the Occupy movement. In this it keeps Marx too far away. Marx’s critical legacy still matters.

It does, however, unhook Marx from the cartoon Marxism of popular culture. It insists on the distance between Marx and the authors of Soviet communism.

Marx and Lenin never met. Neither did Marx and Weber, the stoical voice of classical sociology. Weber is the better additive to Marx, sober and sceptical rather than redemptive in temper. Even Weber, however, was too optimistic in his timing. Who these days speaks of “socialism in our time”?

Ours is not the world Marx diagnosed in the 1840s, or misread in the 1860s. The imperative that we might do better, however, remains.

Peter Beilharz is research professor of culture and society at Curtin University. He is working on a book titled Circling Marx.

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion

By Gareth Stedman Jones

Belknap Press, 750pp, $79.99 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout