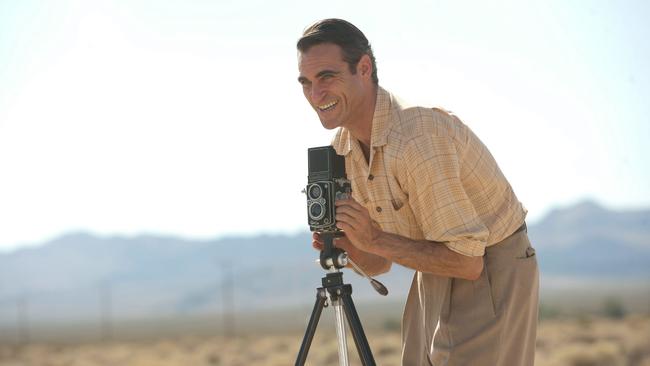

Joaquin Phoenix on working with Gus Van Sant, He Won’t Get Far on Foot

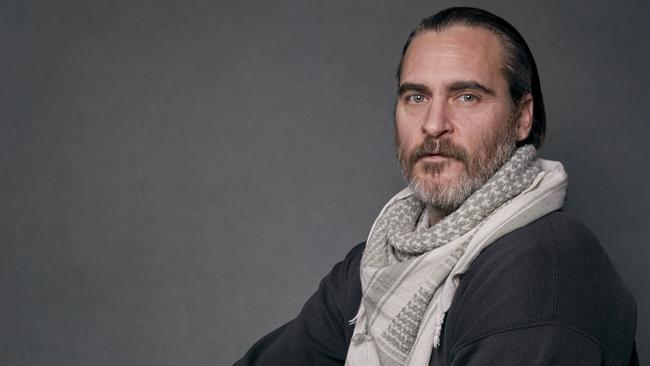

Joaquin Phoenix is quick to talk about the alchemy of collaboration with other actors, yet wary of too much interaction.

Joaquin Phoenix had a problem. Something was missing, something didn’t feel quite right. It was in the middle of the shoot; he talked about it with the director, and they came up with a solution that involved a new scene and a leap into the unknown.

Phoenix was working with Gus Van Sant on Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, a story about addiction, sobriety and creativity. Based on a memoir by John Callahan, the film takes a relaxed, good-natured approach to the task of depicting a troubled, chaotic life.

Callahan, who struggled for years with alcoholism, became quadriplegic at 21 after a car accident. He continued to wrestle with his drinking, his feelings about adoption and his Catholic upbringing; he also began to express himself through sardonic, transgressive cartoons and found a congenial Alcoholics Anonymous group and an unconventional sponsor (Jonah Hill) who helped him redefine himself.

Phoenix became convinced that his character, as part of his recovery, would have wanted to make amends with one particular figure from his past. Van Sant — who had known Callahan well and talked to him years earlier about making the film — decided a new scene could be shot. The actor in question had finished shooting but was brought back for a day. There was barely time to fit it into the schedule and no time to plan the scene, yet it is mentioned by several reviewers as one of the film’s most moving, revelatory moments.

Phoenix says he asked himself whether it was appropriate to invent a scene that hadn’t appeared in the memoir, but decided he could justify it in his own mind, particularly if Van Sant felt comfortable with it. Nothing was scripted but it worked: “In some ways it felt that it was beyond our understanding — it came together and it felt right.”

This is the kind of thing that interests him most about being an actor — the prospect of discovery. “It’s not always possible because of time constraints or because of the filmmaker. But for the last several years, virtually every filmmaker I’ve worked with has approached things in this way. They realise there might be something else that we haven’t uncovered that we might uncover during the process. And that’s so exciting,” he says emphatically. “So much fun.”

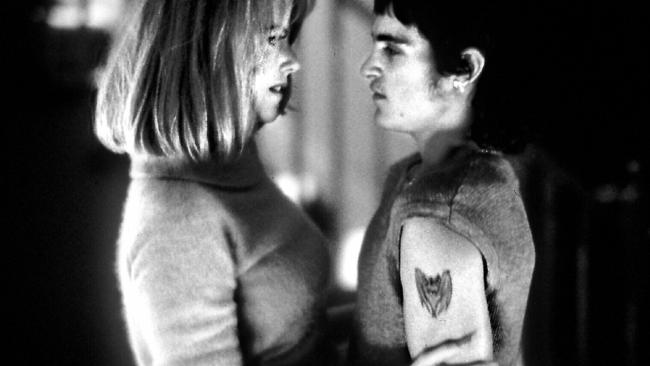

Phoenix was in his early 20s when he last worked with Van Sant, on To Die For (1995), a black comedy starring Nicole Kidman as a woman dreaming of TV stardom who seduces a high school student (Phoenix) and inveigles him into murdering her husband. Infatuated and naive, Phoenix’s character is jittery with longing and lust, ripe for manipulation. This is the film the actor credits with changing his approach to his work, opening his eyes to the rewards of risk and experiment.

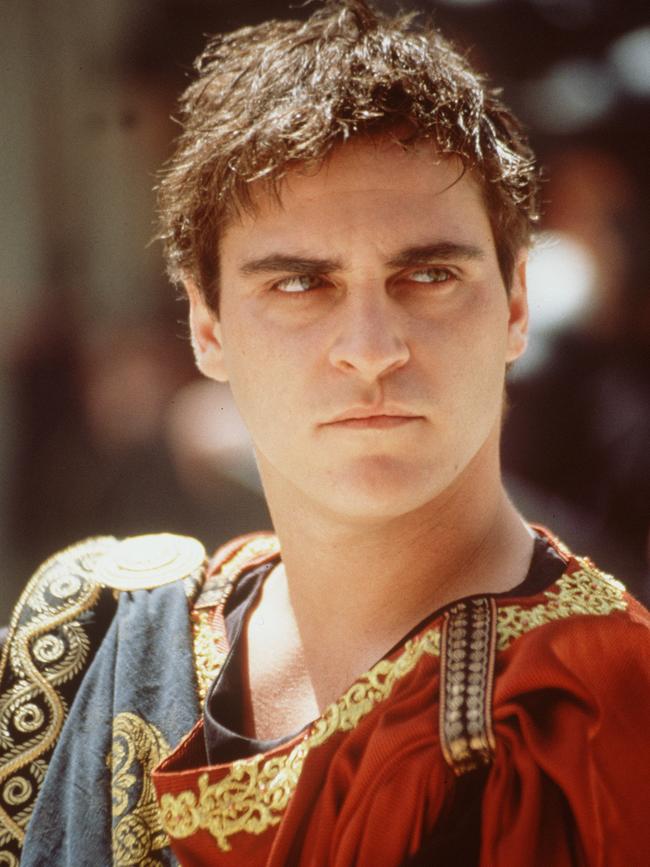

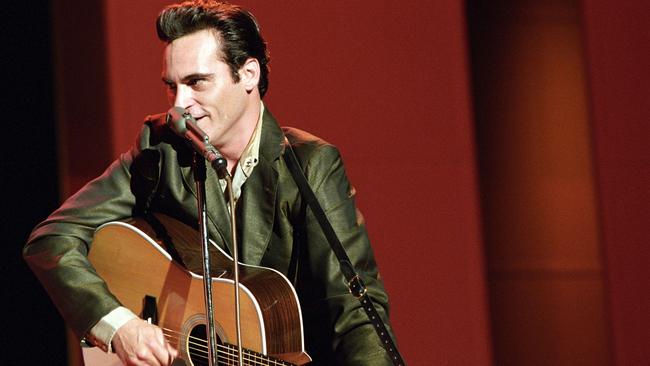

Since then, in a succession of extraordinary performances, Phoenix has embraced excess, uncanny restraint and minute attention to detail. In Gladiator (2000), for example, he’s magnificently mannered as unhinged emperor Commodus. In Walk the Line (2005), playing Johnny Cash, he loses himself in the physicality of the singer and his songs: it’s not a slavish impression but an act of conviction and surrender. Between 2000 and 2013 he found a director whose sensibilities matched his: he made four movies with writer-director James Gray, whose penchant for heightened emotional states is ideally suited to his mixture of expressiveness and withholding.

In Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master (2012) he gives a remarkable performance as an alcoholic World War II vet who becomes caught in the toils of a charismatic leader (Philip Seymour Hoffman) of an organisation called the Cause. Phoenix — head lifted, mouth half-clenched, hair-trigger impulsiveness scarcely in check — is a study in repressed energy, a potent contrast to Hoffman’s bluff, manipulative eloquence.

In Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), a year later, he gave a performance of quiet yearning, as a man who falls in love with the disembodied perfection of his personalised operating system.

Experimentation, with Phoenix, is built on preparation. In Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here, currently in release, Phoenix spent weeks in her company ahead of the shoot, painstakingly readying for every aspect of the role as a traumatised hit man and immersing himself in the world of the film. “He’s an exciting guy to work with. He questions everything, but in a good way,” Ramsay says.

Phoenix refers more than once to the rewards of uncertainty in filmmaking. “The things that feel best are those moments I couldn’t have anticipated, and oftentimes when I try to impose some kind of idea and I think that I’m being clever and I’ve figured something out, those things feel the most false,” he says.

Sometimes it’s a moment, sometimes it’s the shoot as a whole. For You Were Never Really Here, he recalls: “We shot it in six weeks in New York and we really changed a lot from where it started, and that was terribly exciting and it felt dangerous the whole time, I don’t think we ever felt relaxed while making that movie. But Lynne is a very, very special filmmaker and it was incredible to work with her … it absolutely exceeded my expectations.”

Yet sometimes limitations are important, he says. He describes a story he heard about Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs, and the filming of a key scene, an encounter between Anthony Hopkins and Jodie Foster. It cuts between Foster and Hopkins, as she is telling him a story that explains the title of the film. “And apparently the lens and the lighting and the framing, and the depth of field were such that if she moved an inch forward or back it would go out of focus,” Phoenix says. “There was a certain kind of constraint imposed on her. And I don’t know if it’s true or not, but it’s brilliant. The lack of movement in that moment is fantastic, it’s hypnotic.”

He can talk about every aspect of performance but prefers not to watch himself in a finished film. “Generally I try not to,” he says. “If it’s an early cut, and the director wants my opinion or we’re considering doing additional shooting or something like that, then I may watch it. But it’s not something that gives me pleasure and I’m not sure that it’s beneficial or that I learn much from it that might help me improve. It’s never going to live up to the experience. It’s always disappointing to me.”

He says this matter-of-factly, without any sense of regret. The experience on set is his contribution, what he knows of the film. A scene that may be less than a minute on screen can represent something very different for the actor who is involved in it, he says. “You shot for several hours and prepared for it for months; you had so much invested in it and you actually had the experience.”

He can’t anticipate and doesn’t need to know what the audience sees. “Sometimes other people think that you managed to convey that feeling, but I go: ‘This is nothing compared to what my experience was.’ ”

He mentions a recent occasion when he saw a rough cut and felt really taken aback by a particular scene in which he appeared. “I thought: ‘It’s truly awful, it seems really over-the-top bad acting and it’s strained.’ We talked about reshooting it and I was so confused, because I felt like: ‘I know I was coming at it from an honest place, that is what he was feeling, that is the honest and appropriate emotion for that moment, so why didn’t it work? What did I do wrong?’ And it really troubled me.”

Then the director called him back and screened some footage for him that included the scene that had troubled him so much, but in a different order, with different material. “The second time, the emotion completely made sense. And it was just because there’d been some editing around it.” The context made the difference. It’s a story that demonstrates to him how movies work and who is in charge. “This is why I feel the filmmaker is always responsible for the performance.”

He’s also quick to talk about the alchemy of collaboration with other actors, the pleasures of discovery on set, the to-and-fro of working on a scene, the sense of anticipation he feels when he “can’t wait to get to work to see what would happen”. That’s what it was like, for example, filming with Jonah Hill in Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot.

Yet much as Phoenix appreciates what can come out of collaboration, he is wary of talking too much with fellow actors on set. He had an experience that burned him, he recalls. “I remember doing that when I was younger: we did this scene, and we all felt like we’d really discovered something, but we couldn’t finish it because we ran out of time and we had to come back the next day. So that night we got together and we talked about it, and there was a little bit of, ‘wow, that was really interesting’.

“And the next day we went to finish it and it was just dead. It was flat. It was such a mistake. I was like: ‘I will never do that again.’ So now I’m really paranoid about it, almost to a fault. I go: ‘I don’t want to talk about it, let’s just do the work.’ ”

Of course, he says, you can get things wrong, you can make misjudgments. “But sometimes bad acting is just being self-conscious. It’s performative, it’s trying to do something to get a reaction, as opposed to just being.” This awkwardness can happen on location, he says, “if there are people standing watching a movie being made and they call shit out to you, there are a bunch of lights and cameras, things that can be very distracting, it can be easy to become self-conscious and think: ‘F..k, I’m making a movie!’ ”

In You Were Never Really Here, Ramsay recalls, Phoenix was unrecognisable as the burly hit man and they were able to film covertly on New York streets. “Joaquin looked like a construction worker or a bum,” she says, “so no one really took any notice of us when we filmed.”

There have been times Phoenix has appeared to be uncomfortable with the expectations that come with filmmaking, with the demands of publicity and the intrusions of celebrity. Right now, however, he seems invigorated, engaged, ready for more.

Looking ahead, he hopes there’s another movie with Gray not far off. “We’ve talked about a couple of things. I’m desperate to work with him again, so hopefully we’ll find something we can do together.”

He hasn’t done a bona-fide blockbuster since Gladiator, although he has signed up for the title role in DC’s Joker, a film shrouded in secrecy that appears to be an origins story about the supervillain. It is meant to be a stand-alone: it will not lock Phoenix into sequels or long-term commitments, something he has always sought to avoid.

Throughout his career, he never has been really proactive about films.

“I know a lot of actors are constantly trying to develop things and optioning books, and part of me envies that, and thinks: ‘Ah, yes, be assertive, that seems like it’s the right move.’ ” But then, he adds, it doesn’t seem to matter. “Usually when I am ready to work again, the right thing comes to me. I’ve been very fortunate.”

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot opens on September 27.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout