Interestingly enough … The life of Tom Keneally, and his women

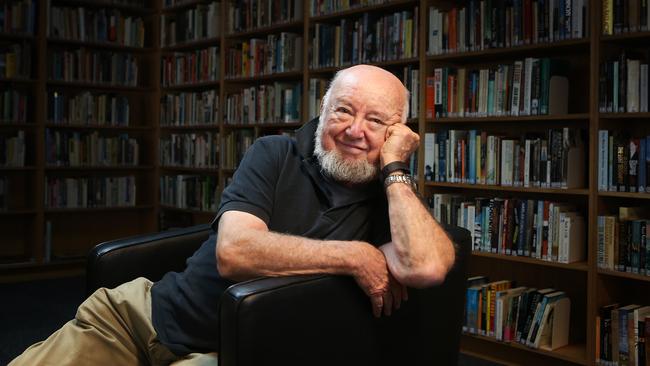

Tom Keneally’s biographer, Stephany Evans Steggall, considers the prolific author’s development of his female characters.

Tom Keneally attended a Christian Brothers college and Catholic seminaries for many years so it is hardly surprising that his early heroes were male. Among them were the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, the maverick priest Charles de Foucauld and the unconventional Cardinal Moran. The only woman among the heroes was Joan of Arc, who features in his 1964 debut novel, The Place at Whitton, alongside another female character, Agnes the witch.

Agnes conducts black masses that involve a mauvais pretre (evil priest). Her extreme behaviour is typical of the absurdities and depravities of the book, which pokes fun at some of the prohibitions and pretensions in a seminary. Agnes is not a credible character, but she is not intended to be in such a darkly humorous story.

The appearances of the phantom Joan to the sick seminarian Verissimo are symbolic of the lunacy that Keneally faced in his last months at St Patrick’s College, Manly, before leaving abruptly in 1960. For some time after he left, Keneally was not comfortable around women and this awkwardness is apparent in his first serious writing. The ex-seminarian stigma remained and he was anxious about appearing ‘‘physically unprepossessing’’, as one cruel priest at the seminary had described him.

He feared he would never be married, yet he believed there was someone out there who was part of him. ‘‘I could feel her presence but I could not visualise her,’’ he recalls. ‘‘But she was the other side of my soul, which is a very shoddy image, and there was an impulse in me to find that person.’’

Keneally married Judith Martin in 1965 and soon afterwards wrote Bring Larks and Heroes, the first indicator of his skill in writing historical fiction. The relationship he builds between Irish marine Phelim Halloran and Ann Rush was no doubt influenced by his own newly wedded state and was intended to transcend the warped views of Catholic dogmatists with whom he had grown up. Nevertheless, Ann, the victimised Irish servant girl in the novel, is part of a very mystical story and she is not quite believable.

The women in Keneally’s subsequent historical fiction are more robust and interesting, reflecting the gathering strength of this genre in his writing. Before hitting his stride as a ‘‘nonfiction novelist’’ (as British critic Alexander Walker described him) he created a few other unlikely women. There is Barbara Glover in A Dutiful Daughter (1971), a book Keneally admits was written by ‘‘a very black young man, whom I barely remember ... looking back to my alienated younger self I think the cattle business is a fair representation of what adolescents and particularly girls would like to do to their parents. To turn them into beasts of the field!’’ The story is about the abnormal life of Barbara Glover caring for parents who have metamorphosed into bovine centaurs.

Keneally’s Joan of Arc stands out as one of his most successful female characters, although the achievement in Blood Red, Sister Rose (1974) is as much about the historic drama and scene painting as it is about the central character. As Keneally’s eighth book in his first decade as a published author, it is positioned at a critical phase of his career: while the previous title, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1972), had marked a turning point in his personal life and affirmed his position as a leading Australian novelist, he had to consolidate this.

Having been accused in the past of not writing competently about women, he felt some pressure to create a memorable Joan. He likens her to Germaine Greer: ‘‘She had the incredible rudeness of the revolutionary, didn’t apologise for her perceptions, and could give the same castrating replies to questions!’’ He describes Joan as freakish but feminine. ‘‘And because she was feminine, a male society punished her for participating in what belonged to it — politics and war.’’ Keneally believed he was writing a feminist novel, in keeping with the times. He dedicated the book to his two daughters, whose presence in his life helped him to understand the feminine perspective.

‘‘It’s the first book about a virgin I’ve read in years,’’ wrote Frank Moorhouse of Blood Red, Sister Rose. ‘‘Virgins don’t get much of a run in contemporary fiction.’’

Moorhouse, who admitted at the time he was not then ‘‘a Keneally reader’’, thought the book was ‘‘an outstanding vivification of some major insights about behaviour’’.

‘’Blood Red, Sister Rose was a book of rare brilliance,” said Simon King, who edited the book for the publisher Collins in London, ‘‘in which page after page sparkles with those rare storytelling gifts that distinguish Tom from so many other writers.”

These were important endorsements to take into the next stage of Keneally’s writing life and to encourage improvements in his development of female characters. A couple of titles that followed were controversial, such as Season in Purgatory (1976), for which he had to confront claims of plagiarism. He did not recover his place until Schindler’s Ark in 1982, although A Victim of the Aurora (1978) and The Cut-Rate Kingdom (1980) both offer telling insights into Keneally’s exploration of relationships.

In A Victim of the Aurora he probes attitudes to homosexuality and adultery. Elderly Anthony Piers is in confessional mode about his love life: ‘‘When you remember such women you know that even now, in a Laguna Hills nursing home for decaying plutocrats, you are still in love with them.’’ Lady Anthony Hurley tells Piers, when he begs her to marry him: ‘‘Marriage isn’t a matter of desire. It’s a matter of placid companionability.’’ Piers reflects: ‘‘Admittedly I was always easily infatuated ...’’

Keneally himself is easily infatuated and has talked about ‘‘profound friendships’’ with women. He has a lot to say about marriage and fidelity in various books, including The Cut-Rate Kingdom, in which the prime minister, Mulhall, is naive and foolish about Mrs Masson, the straying wife of a general. When Andrew Peacock launched the book he described the Mulhall-Masson affair as “the most unerotic account I have read!” Keneally replied that he had been accused of being too erotic in two earlier books. ‘‘This time I decided to tone it down a bit.’’

In Chief of Staff (a 1991 sequel to The Cut-Rate Kingdom) and A Family Madness (1985) it is the women who are destroyed by extramarital affairs. Dim Lewis in Chief of Staff is unhappy with her ‘‘marginal and secretive life’’, poor compensation for the loyalties of a marriage of ‘‘secret pleasures and griefs’’. Her lover, Galton Sandforth, is more concerned for his standing in the work and social environment. Terry Delaney in A Family Madness wants his wife Gina to be ti mon seul desir (“you, my only desired one”), but his obsession with Danielle Kabbel destroys the marriage.

After 20 years of writing novels Keneally could say that he liked writing about women, but he has always believed they are often deceived and often wrongly supportive of their men. He has a great deal of feeling for Danielle and Gina. ‘‘Gina is such an honest woman,’’ he says, ‘‘but honesty is often not enough in a relationship.’’

Keneally’s fondness for his female characters becomes evident in the more recent books, such as Woman of the Inner Sea (1993). ‘‘I never found myself in a position,’’ he reflects, ‘‘where I said to myself, ‘Tom, how do you reckon a woman would feel in this situation?’ I believe, rightly or wrongly, that I knew. I didn’t have to grope for what I would have considered maternal or feminine responses.’’

Most of Keneally’s novels are based on real events and real people. He has mastered the art of creating fiction around facts, but not always without repercussions. An American woman agreed to his using her story for Woman of the Inner Sea on the condition her name was not revealed. Caroline Baum, however, was distressed when she recognised herself as Alice the journalist in The Tyrant’s Novel (2003).

Keneally now enjoys speaking in a woman’s voice. He has a soft spot for his 2012 novel The Daughters of Mars, he says, because of the Durance sisters: ‘‘I love those two girls.’’ For that book and Shame and the Captives the following year, he tried ‘‘to understand women — a late-blooming endeavour of mine’’.

It will be interesting to see how Keneally re-creates his latest female character, Betsy Balcombe, in his forthcoming novel Napoleon’s Last Island. Will she eclipse the great French hero?

Interestingly Enough: The Life of Tom Keneally

By Stephany Evans Steggall

Black Inc, 416pp, $49.99

Tom Keneally’s next novel, Napoleon’s Last Island, will be published in November by Vintage/Random House.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout