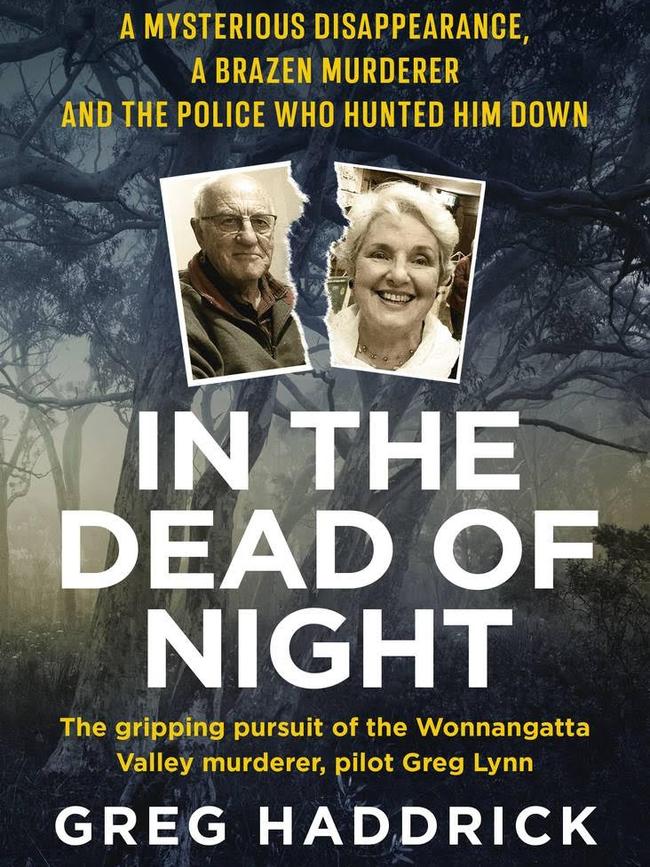

Inside the gripping pursuit of camper killer Greg Lynn

A couple murdered at their campsite; a Jetstar pilot on trial. A new book unpacks the high country crime.

In June a five-week trial in the Victorian Supreme Court ended with former Jetstar pilot Greg Lynn being found guilty of murdering 73-year-old Carol Clay at an isolated campsite in the Wonnangatta Valley in 2020.

Clay had been shot in the head at close range. Lynn was acquitted of murdering her fellow camper, and long-time married lover, 74-year-old Russell Hill.

For Greg Haddrick, the race was on to be first to deliver a book about one of Australia’s most high-profile and controversial murder cases. (The hurry was such that the book went to print before sentencing.) But is there anything left to say about a case that has been so thoroughly and recently raked over in newspapers and on television? And can Haddrick maintain the narrative tension in a story in which not only the characters and plot are already well known, but also the ending?

The answer to both questions, I’m happy to say, is “yes”. Haddrick tells a riveting story while also finding room for some astute, and occasionally mischievous, authorial interjections about the law and the legal system.

I could have done without the book’s one-page opening chapter, taking us back to “our earliest days in the African savanna” where “our predators waited til night. In the darkness, they knew we were weak. To see dawn, we had to be wary. Quiet and cautious”. None of this Scooby-doo spooky talk has anything to do with the story that follows about a quarrel that led to two killings and a macabre attempt to dispose of the bodies.

Haddrick tells the story chronologically, starting in March 2020, when police in the regional Victorian town of Sale received photographs of a burnt-out campsite and a white Toyota LandCruiser four-wheel drive. The owner of the LandCruiser, a retired logger named Russell Hill, had been reported missing by his family. Some days later Carol Clay’s family contacted police. Carol was missing too. It turned out that Hill and Clay were in an extramarital relationship, unknown to Hill’s family, and had gone camping together in the remote Wonnangatta Valley. Hill was an experienced bushman and the case quickly escalated from a missing persons investigation to a likely homicide.

By the time it reached court, the case had been reduced to its essentials, with Greg Lynn the only suspect. But in the beginning there were several possible suspects. One was the “Button Man”, a loner who lived in the Valley and was “a little crazy; he hated being disturbed, had extremely good bush skills and had a four-wheel drive”. Another was a man to whom Haddrick gives the pseudonym “Tom Collins”, who lived an hour away from the crime scene, owned a gun and a four-wheel drive and had been a “strong suspect” in another murder a couple of years earlier.

Haddrick skilfully reconstructs the investigation, showing how Victorian detectives tracked down every person who was in the Valley during the weekend when Hill and Clay vanished, then ruled out possible suspects one by one until only Lynn was left. Haddrick is also very good at evoking the primal wilderness of the Wonnangatta Valley, where several other people had recently vanished without trace, where mobile phones were useless, and where tracks sometimes went nowhere.

The style and pace of the book change after Lynn’s arrest, with Haddrick relying on the inherent drama of, first, the police interviews and, second, the trial itself. While the author admits in an afterword to having “imagined” some of the book’s dialogue (Haddrick was a producer and sometime scriptwriter on the imaginative “true crime” series Underbelly), he sticks dutifully to the record in these sections, quoting verbatim from the transcripts.

By the time he was pulled in for questioning, Lynn had worked up a detailed and plausible alibi, and Haddrick gives a gripping account of the detectives’ efforts to dismantle his alibi.

The chapters devoted to the murder trial are equally compelling. The protagonist here is not Lynn but his barrister, Dermot Dann KC, who tears strips off more than one prosecution witness in his efforts to discredit the evidence and to portray both the police investigation and the prosecution as fundamentally unfair to his client.

During the trial Dann convinced the judge to exclude a chunk of prosecution evidence on the grounds that it had been improperly obtained. The police, he argued, had tricked Lynn while visiting his home into thinking he was not a suspect when he was.

“In other words,” Haddrick interjects, “it is more in the public interest to discourage police from being a little deceptive when chatting with someone in their kitchen, in an effort to discover the truth about a brutal double murder, than it is to have all that evidence for murder presented to a jury at the trial. Maybe he’s right. Someone really should ask the public.”

The judge was also unimpressed with the way police had cajoled Lynn into disregarding his lawyer’s advice to answer “no comment” to every question. This, too, according to Dann, was “unfair” to the accused.

Haddrick clearly disagrees. “If the person being interviewed is a very clever psychopathic killer, and the consequence of keeping him talking until he ignores his legal advice is that it might see him brought to justice … most members of the general public would think that’s a brilliant piece of policing.”

A drier account would have omitted such asides, but they probably reflect what many readers will be thinking. Haddrick says he wants his book to “bring the reader into the immediacy of the events it recounts”, and he achieves that in spades. Buy it before the appeal.

Tom Gilling’s most recent book is The Diggers of Kapyong.