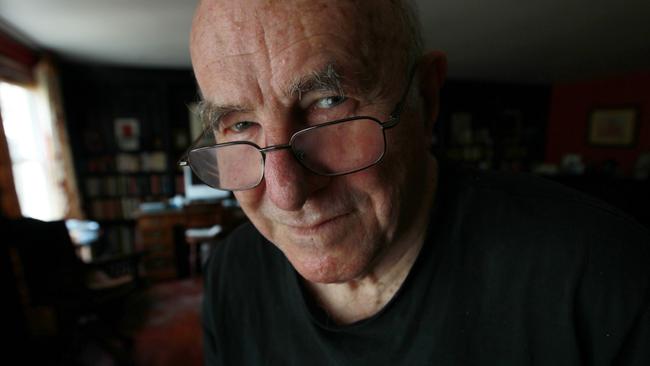

Injury Time, Clive James the poet’s elegiac reminiscences

Clive James has had six years he ‘wasn’t meant to have’ and in the face of death has written some of his best poems.

It must be five years or more since a media group asked me to film an obituary for Clive James. I refused not because I didn’t believe his death was looming but because I thought I could talk about him when the time came, if need be. James, memoirist and interviewer extraordinaire, couldn’t be more conscious of the fact the announcement of his imminent death from leukaemia was premature. At the time it was based on the best information available.

And so we find this made explicit in a fine poem, Initial Outlay, and throughout this collection, Injury Time, which has James’s characteristic meandering and meditative charm together with an added sombre note, a sense of the shadow of the valley, though this apprehension is the subject of some irony.

Death didn’t happen and the joke fell flat,

And bit by bit I came alive again …

The distant thunder of the rolling dice

Grows silent, as if death had quit the scene …

And this will make, since I fell ill, six years

I wasn’t meant to have ...

Six years. James has always been a fine poet with a considerable mastery of traditional forms as well as a marked capacity for the elegiac (not least in poetic reminiscences of his parents, the mother who brought him up alone, the father lost in the last days of World War II). “The guiding father is a theme for me / That aches a long way down”, he writs in one poem. But the peculiar and defining quality of Injury Time is that the sense of mortality is all at once intense and leisurely. This is an impassioned and ruminative book by a man who became famous for other things: a thousand people would have seen James make an idiot of himself in his television travels or interview Katharine Hepburn to every one who had read a poem by him

And it’s also true that in strictly literary terms the best of James’s memoirs, especially the masterpiece Unreliable Memoirs, about his suburban Sydney childhood, belong to a higher plane of achievement. Yet the poems underlie everything else James does because they demonstrate his absolute seriousness about language.

In any case this book is a fine volume of poems and the fact it has such a sombre background, and at the same time is rueful about the accelerations of mortality, gives it a distinctive and impressive moodiness: this is not the verse of a part-time player, this is the work of a man who presents himself as having nothing but poetry left.

The temporal ironies are all there in James’s the foreword: “I should have known better than to flirt with the metallic music of downed tools.” And again, “Remembering how wrong I turned out to be when I thought the poems in Sentenced to Life would be my last.” But he is just a little qualified when he says, “But I can be fairly sure that I am by now, more or less done with the short lyrics.”

Well, may he live forever. Whatever else you think of James, his poems have that absolute deliberateness that is the hallmark of an artist who lays himself on the line and has no fear of the implicit egotism of the performance. The book begins with a piece of self-memorial: Return of the Kogarah Kid is an “inscription for a small bronze plaque at Dawe’s Point” and it has a music and a gravity that carries us back to the Greeks though it could only be James.

“Here I began and here I reached the end. / From here my ashes go back to the sea … / Do the gulls cry in triumph, or distress? / In neither, for they cry because they must, / Not knowing this is glory, unaware … It is just / That we, who learned to breathe the brilliant air / And first were told that we were made of dust.”

James has found a steady music and some strange power of composure in the sustained intensity of this long goodbye. What could sometimes be cavalier and a bit cloaktrailing in James’s work now has an inevitable reference that feels earned.

His friend Peter Porter admitted in his forlorn modest way that the death of his first wife had provided him with a great inspiration — which was true, it was the subject of his greatest work — and the funny thing is that something similar is true of these James poems written in the face of a death that has not had the stealth or the swiftness of any thief in the night but has rather made his presence felt by taking the colour, bit by bit, from the day.

He will refer to Racine’s Phedre and say how she says “death has taken clarity / Out of her eyes / To give it to the world” and suddenly we are with him in a recognition of supreme art that is never separate from the pulse (whether steady or flickering) of life.

The aspect of James — arguably the brightest but also the most flyaway of the famous Australian expatriates — that has always made him slum his way towards art with a critic’s knowingness is here in abeyance: the apprehension of art and literature has lost its swagger, or rather the Mercutio-like wit is in service to a deeper poignancy. “Night is at hand already: it is well / That we yield to the night. So Homer sings, / As if there were no Heaven and Hell, / But only peace. / The grey dove comes down in a storm of wings. / Into my garden where seeds never cease.” A page or two later James says in another poem enunciating how he will take his farewells that he would like to bequeath any power he has to his granddaughter, and adds “I shall renounce them at the fall of night / As I move on to Elysium”.

This shaping awareness of the haunted halls of humanity’s afterlife has its own grandeur even though, as a poet, James has always tended to use his mastery of craft as a way of riding past the looming mysteries of art and the soaring towers of achievement, topless and unreachable. Here in the poem he decided not to make the title poem (because that would be, he says, to give himself airs) there is a homage to Beethoven that gains an enormous plangency from the Hamlet-derived title The Rest is Silence and from the fact Beethoven’s deafness might have felt like death to him. Again James allows himself to elevate his diction — “the upsurge of the sun/Is written in the stars” — and who could object.

Over and over in this book James commands admiration by something more than turning tricks, though the magician’s skill still has its wonders:

Now my light fades. The stars are on display

In the dark night, not the bright sky of day.

At the same time that Injury Time is a meditation on mortality with the poet’s personae, the voices he assumes and fabricates, so many ghosts that might not have achieved substance, is also a book about the world and James’s own instantiation of WB Yeats’ magnanimous boast, “And say my glory was I had such friends”.

There’s a lovely poem in honour of that perfect gentle knight George Russell, the medievalist, that includes a bit of the old Clive dipping his lid to the Bard of Bunyah (“It’s only justice if Les cops the Nobel”). It also sums up a man with beautiful manners, the kind who’ll come no more, who could say of his wife’s lamingtons, “the world’s supply is here”, a man who “took in, with ruined lungs, just enough air / To prove you could still smile” and who could also say of great art and music “… Any works that burn / The brain like that are works of God … / They speak of what He lost …”

It’s a lovely poem and so too is the soliloquy James puts in the mouth of Shallow, that doddering old justice of the peace in Henry IV. “My name is Shallow. Lend me credit, pray, / If I, had at this stage, sound deep once or twice. / They called me ‘lusty Shallow’ in my day. / But time ensured that I would pay the price … / I, too, have lived: a small life, but not mean. / Jesu, Jesu, the days that I have seen.”

And then there are a couple of poems about the woman James, like the world, had a crush on: Princess Diana. (His gave him a window seat with her at restaurants.) His lacrimae rerum poem about her talks of the “lost earring” and the “crushed Mercedes”. Then “Choral Service from Westminster Abbey” says the circumstances of her death were “Almost as if she wanted to be gone”. And then, boyishly, roguishly, like the old Clive, he writes “You well might smile, / But she could smile as if she were the dawn / All set for a night out.”

Injury Time is a significant achievement and lasting testament to a man who is a marvel of a wordsmith and who in the face of a death sentence that has allowed him injury time (“This is a pretty trick the fates have played / On me, to make me think that I might die / Tomorrow, and then grant me extra time”) has written some of his best poems.

They are not the greatest poems to have come out of this country: that place would be reserved for Porter or Les Murray, but this is a book by a true artist. It will ring in the ears and tug at the heart of any reader who has ever prickled at that weird uncanny thought that poetry — of all things — can sound like some fragment from the mind of the spirit that moves the sun and other stars.

Peter Craven is a literary critic.

Injury Time

By Clive James

Picador, 95pp, $34.99 (HB)