Indigenous art’s journey traced in three pivotal books

Three pivotal books reflect indigenous art’s journey from antiquity to modernity.

The history of art is an ever-changing story, and so it is proving with the brief, tumultuous saga of the Aboriginal art movement, a sunburst of creative energy that has already done much to change the way Australia sees itself and the world sees Australia. For many admirers of contemporary indigenous art-making, the origins of the movement can be traced to the little settlement of Papunya, west of Alice Springs, where a group of desert men began painting on boards and canvas in the early 1970s. Some prefer to look back even further and cast their focus on the cattle station at picturesque Oenpelli, on the western edge of Arnhem Land, where bark painting for sale to outsiders was pioneered just over a century ago.

There were Aboriginal artists and sketch-makers aplenty on the early frontier in Victoria and NSW, and the roots of the indigenous art-making tradition reach back deeper still in time, down the millennia. The painted and engraved rock art and cave art that survive across the length and breadth of the continent form the longest continuous sequence of image-making found on earth. If the precise date and true point of origin of Aboriginal art is contentious, so too are the details of its story: the arc of its ascent, the nature of its trajectory, its relationship to traditional indigenous culture and to developments in the wider world. At least the key events in recent years since its emergence as a contemporary art current are established and the different regional schools well defined, but the movement’s evolution and its ultimate fate remain unclear. Does it have a future as an independent, autonomous tradition or is it destined to merge with contemporary culture as a piquant entertainment, to become fodder for international biennales and exhibitions, to flow in placid fashion into the vast, restlessly surging ocean of world art?

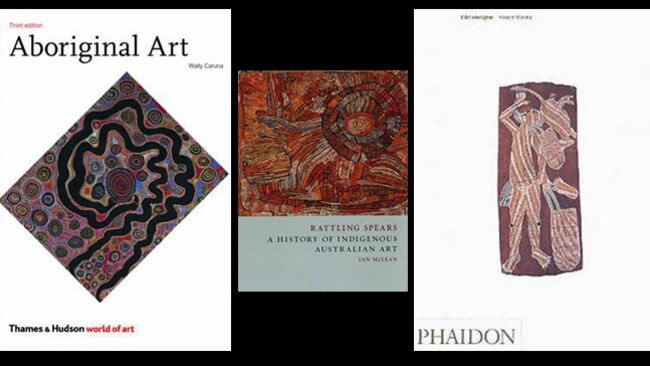

Its significance as an agent of transformation in this country is not in question. Already there have been two comprehensive general histories of Aboriginal art by prominent credentialled experts, Wally Caruana and Howard Morphy, and both are works of impressive sweep and lasting influence. These are now joined by a third, yet more ambitious overview, Rattling Spears, by the leading academic scholar of the field, Ian McLean. Each of these accounts offers a detailed chronicle of the movement’s various stages. Each tells the same tale yet casts it in a different light. Each bears the date stamp of its time of composition, so that together they illuminate Australia’s shifting attitudes towards indigenous culture and the gradual alteration of the tale about Aboriginal art-making we tell ourselves. What emerges is intriguing: the shadow of Western art history and its preference for clear-cut periods is ever-present, as is the desire to claim and celebrate indigenous art and to keep it in its defined, distinct category.

Caruana was first out of the blocks with his guide to the field, Aboriginal Art, first released by international art publisher Thames & Hudson in its World of Art series in 1992, when the author was midway through his long tenure as senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Art at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra: it is in its third edition and still sells well and shapes ideas about Australia around the world. Caruana’s chief ambition is to highlight the place of indigenous culture in the landscape of world art by explaining its context: “Art is central to Aboriginal life,” he begins: “Whether it is made for political, social, utilitarian or didactic purposes — and these functions constantly overlap — art is inherently connected to the spiritual domain. Art is a means by which the present is connected with the past and human beings with the supernatural world. Art activates the powers of the ancestral beings. Art expresses individual and group identity, and the relationships between people and the land.” Before the time of settlement, Aboriginal art was the backbone of ceremonial life. Now it looks outwards, it is a gift to outsiders. As a result, “a significant body of art has emerged which is intended for the wider, public domain”.

The standard categories that shape the presentation of indigenous work today were well established when Caruana was writing: there was art from remote Aboriginal Australia and art made by indigenous men and women of non-traditional, urban background. The traditional work had an aura of the classical about it, whether it came from the desert, the Top End, the Kimberley or the Cape. Much in this version is still accepted and is echoed by Morphy and McLean; indeed, the three experts occasionally describe and reproduce the same paintings. Morphy is well known as an admirer of the Yolngu artists of Yirrkala and gives detailed accounts of their work, its stylistic conventions, its meanings and encoded clan designs. Caruana, as an enthusiast of the mid-20th century bark painters of central Arnhem Land, outlines the links between the works made by members of a particular family group to exemplify the way ideas and emblems are passed from artist to artist and traditions receive individual interpretation. Thus England Banggala, the Rembarrnga patriarch of the Cadell River, was once well-known for his bark depictions of the rainbow serpent, as was his daughter, Dorothy Galaledba, her brother-in-law, Jack Kala Kala and her husband, Les Mirrikkuriya, whose use of coloured ochres and strongly diagonal designs secured him widespread recognition: Mirrikkuriya won three National Aboriginal Art Awards, in 1987, 1991 and 1992, and the rare examples of his barks still on display in public galleries stand out at once for their elegance and force. Yet he is largely forgotten in our day.

This is a common phenomenon in the recent record of Aboriginal art and it is brought to light by Caruana, whose overview of the tradition picks out several once-famous masters now virtually lost from memory: among them the first successful painters from Lajamanu in the Tanami Desert, Abie Jangala and Peter Blacksmith, east Kimberley ochre painter George Mung Mung and northeast Arnhem Land ritual leader Liwukang Bukurlatjpi. The significant point these artists had in common was their prominence within their own societies: they were figures whose traditional authority made them pre-eminent, rather than artists groomed and schooled in Western-run art centres, and their eclipse renders plain a little-noticed divergence between the art market’s assessment of value in Aboriginal works and the priorities of the indigenous realm itself.

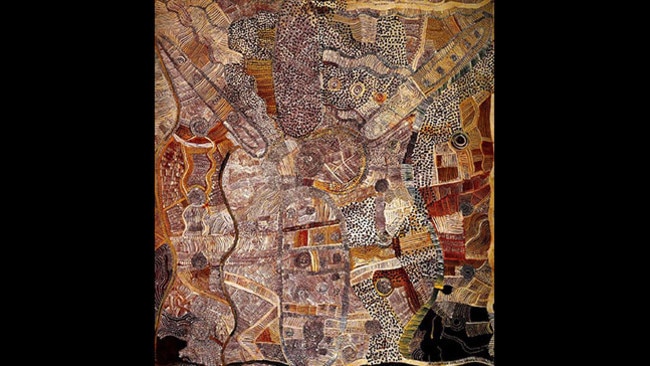

Of course many of the works Caruana singled out in 1992 as masterpieces of the tradition remain in high regard: he gave prominence to several of the jewel-like early boards from Papunya: Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri’s lovely Wild Potato Dreaming, Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula’s Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, perhaps the most famous of all desert paintings, and Timmy Payungka Tjapangati’s Secret Sandhills. The reputations of these works have only grown in stature, they stand among the icons in the canon, they seem today like distant treasures. Strikingly, though, there are many desert masters whose names are in eclipse and entire stylistic phases in desert and Top End art that have been relegated to obscurity and are no longer hung in museums or seen as vital records of indigenous expression.

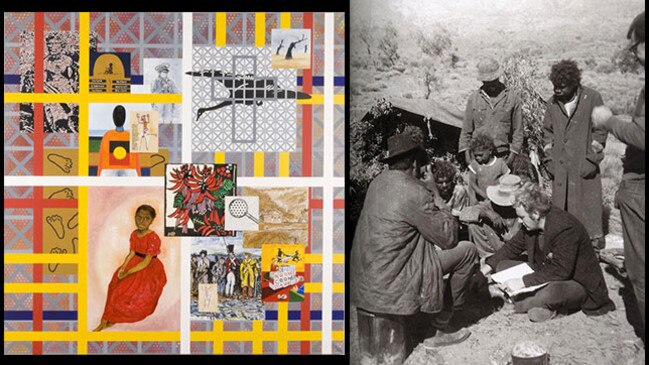

Caruana’s survey also provides an intriguing snapshot of the subsidiary place that was still being accorded to urban Aboriginal artists just a generation ago. There was already a rich field of work to ponder, from Trevor Nickolls to Gordon Bennett, but in the early 1990s the position of city-based indigenous artists was still embattled, theirs was an art of campaign and protest, with assertions of identity at its heart. “When seeking to accept Aboriginal art, Australian society at large perceived traditional forms alone as the authentic expression of Aboriginality,” Caruana wrote.

The place of indigenous art also reflected the slow changes in Aboriginal politics. The rhetoric of reconciliation was in the air but the social landscape seemed bleak and the architecture of native title was only just being devised. When he came to set down a new chapter for his latest edition three years ago, the picture was quite different. The positions of urban and traditional art had changed, if not reversed entirely. Institutional power had flowed into the hands of the city-based Aboriginal cultural class: the best-known indigenous figures in the art world were now drawn from their ranks. Caruana changed his assessment: “Assured of cultural continuity, a new confidence is evident in the work of a generation of artists who have remodelled their forebears’ strategies to express traditions and culture in the public arena and to reflect their contemporary realities.”

■ ■ ■ ■

This change of emphasis marks a fundamental shift: indigenous art has travelled, in just 20 years, from the antiquarian wings of fine art museums to the sleek spaces of contemporary galleries; and the bush is no longer the sole litmus of authenticity or value. The journey’s course and its intended goal seem clear enough to a range of art world administrators and insiders, as Caruana’s postscript underlines. “Aboriginal art and artists have been incorporated into the mainstream of Australian art, and to a lesser degree the international art arena.”

Sydney, Venice, Moscow, Kassel — the Aborigines are there, while the newly reconfigured National Gallery of Australian is primarily an exhibition space for its enormous collections of indigenous work. An upward glide! “Aboriginal art, once admired solely for its antiquity, has staked its claim on the artistic map of the modern world, as being among the great expressions of the human spirit and human experience.”

Most of Caruana’s successors in chronicling the movement subscribe to this broad master narrative. It is well on the way to becoming the Australian conventional wisdom. It is largely shared by the anthropologist and theorist of cross-cultural encounters, Morphy, whose magisterial overview of the Aboriginal art tradition remains authoritative almost two decades on. Much was new since the publication of the first book on the field five years earlier: just as much has changed in the contemporary art world, and in remote Aboriginal Australia, since the late 90s, when Morphy was framing his analysis. He wrote at a time of relative optimism for indigenous Australians, when native title law was newly established, and the Northern Territory intervention was not yet a dream in a politician’s mind. High-end art market demand for fresh works from remote communities was exploding, it was a golden time for painting in the Top End and Kimberley, the movement was just beginning to touch the Pitjantjatjara lands of the South Australia desert. Everything seemed possible.

Morphy’s core theme was engagement. He positioned Aboriginal art as a form of conscious dialogue with colonial history and presented the artists as active proponents of their cultural values. He wrote: “Aboriginal art has maintained value to its producers while gaining in value to outside audiences. The appreciation of art across cultures reveals shared sensitivities to visual forms while allowing for aesthetic values and interpretations of forms to differ.” Given this, there was a space for indigenous work to reach out into the world in fruitful fashion. A testing time had been successfully negotiated. “The power of European culture threatened at first to destroy the Aborigines, not by its intellectual or philosophical power, but through the force of arms and the appropriation of land. It was through art Aboriginal people maintained their continuity with the land until circumstances changed so that they could hold on to it physically.” This “two worlds” view and this progressive account of Australian history provided a fresh lens through which to view the various episodes of Aboriginal art in modern times: the early barks of Arnhem Land were attempts to explain the depth of Yolngu culture to outsiders and make claims to land and sea; the desert canvases were topographies, the abstract-seeming east Kimberley ochre paintings were representations of land and title deeds to territory as well, despite the disruptions traditional life had suffered in the pastoral regions of the far northwest.

In retrospect it becomes clear the mid-90s were the high point of mainstream enthusiasm for the idea of classicism in Aboriginal art. Old masters were continually being discovered in new art regions, and encouraged to record their world views in paint; indigenous culture was being embraced by the mainstream; there were desert designs in mosaic at Parliament House in Canberra and funerary poles from Arnhem Land took pride of place in Sydney shows of contemporary art. It made sense to argue, as did Morphy, that “colonialism has been a struggle over the aesthetics of the Aboriginal landscape”, and Aboriginal people had won; the acrylic paintings of the day, “whose form and design have begun to influence contemporary Australian art in fundamental ways”, were the work of the victors of the desert crusade.

This approach gave equal weight to mainstream and indigenous cultures and ways of seeing, and tended to avoid any making of aesthetic judgments from an outside perspective. The way to look at Aboriginal art was to seek to see it through Aboriginal eyes, to know something of ritual, kinship systems, mythological beliefs and customary law. In his book’s key chapters, Morphy is at great pains to explicate the work of several Arnhem Land schools in detail. He walks the ground shown in a picture of Trial Bay by Banapana Maymuru, the son of his chief informant, Narritjin; he teases out the iconography of “magnificent” barks by Johnny Bulunbulun and Jack Wunuwun.

He is almost equally receptive to the cause of urban indigenous art and holds out the hope that Aboriginal work eventually will hold its own in all the world’s great galleries and exhibition spaces. For Morphy, art’s principal task is communication, it can bear a message and a meaning beyond itself. At the outset of the 20th century, at the dawn-point of European modernism, artefacts from non-Western societies were being widely collected and increasingly admired. African, Oceanic and Native American images and carvings influenced the avant-garde from Picasso to Breton — and this influence served as a solvent, shifting the accepted definitions of art and sculpture, releasing Western painters from the straitjackets of tradition and representation.

That pathway was one the advocates of Aboriginal art in Australia a generation ago were keen to see followed once again, as urban artists of Aboriginal background came to prominence: exposure on the national and international stage, the emergence of indigenous paintings and sculptures from their hands as work of value equivalent to the productions of contemporary Western masters. Hybridity and fusion were in the air; and the vast scope of contemporary international art curation left a space for a revaluation of Aboriginal aesthetics: “The solution forced by the nature of contemporary Aboriginal art was the recognition both of its plural nature and of the consequences of this plurality for Western art-historical theory.” A campaign had been waged and was continuing: a battle to persuade mainstream Australians to see Aboriginal people and their world. And by 1998, that cause seemed to have borne fruit.

“Aboriginal art is now being incorporated in the general discourse over Australian art,” Morphy declared. “It is collected by the same institutions, exhibited within the same gallery structure, written about in the same journals as other Australian art. This has come about through the Aboriginal struggle to make their art part of the Australian agenda.” There was even hope for the further spread of indigenous artworks outwards, into foreign markets and high-end galleries of contemporary art.

Those concerns and expectations have endured, and they resurface, transformed for new times, in McLean’s account of Indigenous Australian Art, a book so elegantly produced it seems to belong in a white-cube exhibition space. If Caruana’s guide served to introduce the masters of Aboriginal art, and Morphy explored the culture behind those masterworks, McLean wants to situate them yet more firmly in the bright light of the present day. “Indigenous art has a modern history,” he announces. “It is one of many modernisms produced from modernity’s global reach.” By meeting modernity, Aboriginal artists became modern artists, “eventually making for themselves a place in the discourse of modern art”. McLean thus moves beyond Morphy’s position, which sees Aboriginal art and Western art as two distinct domains and accords them equal weight: for McLean, the contemporary art world is a heaving, bustling bazaar, in which a thousand forces and cultural currents are constantly mingling until they interpenetrate. The key idea here is “transculturation” — traditions are appropriated, shared and negotiated between indigenous and non-indigenous cultures, and new horizons open up.

McLean also sees a break between himself and his predecessors. He describes his book as “the first full art-historical narrative” of the field. He is neither a professional art curator nor an anthropologist but a conceptual academic, a merchant of ideas. His previous book, an anthology of critical essays on indigenous art, had an intriguing title: How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art. In a sense, Rattling Spears is his attempt to make good the claim and tell the story of the movement from its beginnings through to the variegated indigenous art world of today.

His tale has much in common with those told by his precursors but reflects, inevitably, the tumultuous events that have transformed the landscape in the past decade: the vogue for new art from the desert and remote bush; the price inflation; the global financial crisis of 2007 and subsequent art market collapse; the vast extension of the state-subsidised culture sector in Australia; the emergence of a new generation of contemporary Aboriginal artists making works well suited to present art-world fashions and trends. His story begins, as it must, with symbols and with emblems: with the visual language of the far past, preserved on the rocks and cave walls of remote Australia. There are the now-familiar primal scenes at Oenpelli and Papunya, then comes the gradual development of the Western taste for Aboriginal designs. Would the outside world destroy, through its enthusiastic embrace, what it had found? “While Western experts in anthropology and the art world had been enthusiastic about indigenous art in the 1950s and 60s,” writes McLean, “few believed it would survive the next generation as modernity took its inevitable toll on indigenous traditions. The reverse proved to be the case.”

He goes on to recount an epic cultural revival: “Like so many Italian Renaissance city-states, art centres began to appear in communities across remote Australia, each with its own look.” They became the powerhouses of remote contemporary art but they were also agents of change, not only encouraging old men and women of authority to make art from their belief systems but also spreading the normative influence of the market and the outside world. In short, they were prototypical spaces of “transculturation”. The climax of this community-based art enterprise was also the time of its incipient dissolution: “Indigenous art began to look like a Western art movement, with a few leading art stars and iconic works leading a large second order.” The supply of old men and women to turn into bankable painters eventually dried up: mid-grade works flooded galleries and “mini-celebrities” came and went, thus proving “indigenous art was no different from any other successful modernism”. Then the crash hit. All the hype and hysteria was washed away: collections were dispersed; even prominent, well-known artists could sell nothing and abandoned their work.

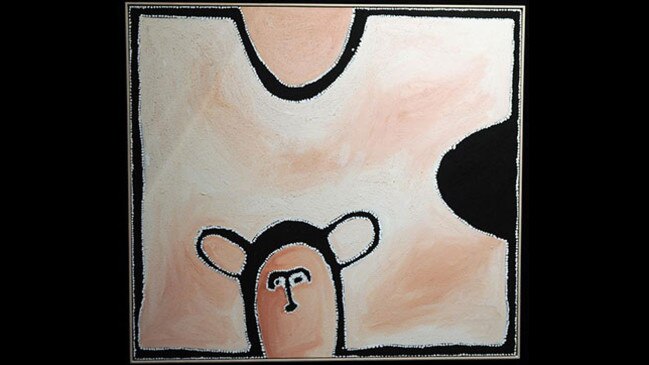

What remained amid the debris? McLean identifies a subtle school of semi-abstraction, opening “on to the primal bedrock of visual language” — a school he likens to the more cerebral currents in modernism, with Kimberley artists Paddy Bedford and Rover Thomas, and Yirrkala’s Nyapanyapa Yunupingu as its leading lights. Work of this kind has drifted far from overt Aboriginal iconography — it has become something else, pure painting.

This raises a disturbing question, to which McLean provides a characteristically complex answer: “If all that is left is an aesthetic shell, what will be the future of remote indigenous art? Is there any longer a difference between indigenous and other contemporary art — not because indigenous art has become fully acculturated into a Western type of contemporary art, which it clearly has not, but because the transculturation increasingly occurs at the formal level? These are questions that only the artists can answer: but they are questions that emphatically confirm the art as contemporary.”

Shifting, ambiguous terrain. There is, though, one strain of Aboriginal art-making that is undeniably contemporary, and thrives in that spotlight: urban indigenous art, whose leading practitioners are driven by a “deep anger at historical injustice”, and treat the legacy of colonialism as the foundation of their work. These themes were already familiar in the 90s, but the cast has changed. In succession to figures like Michael Riley and Bennett, McLean takes engaged, polemical, artists such as Vernon Ah Kee, Michael Cook and Daniel Boyd, all strongly branded types in the contemporary art bazaar, as exemplars of this current. They are the new spear-rattlers, the keepers of the flame. Indigenous art has begun its move out into the world, it has taken the world’s impress into itself, and is displaying its own ways of sight and thought to that wider world.

This new tradition in the making needs a new art history and here it is, in McLean’s version: a history written on the wings of theory and flying high — a history for the age of collaborations, cross-pollinations and multinational art projects, when culture is a component of identity rather than the core of a ritual tradition.

Indigenous images have not been appropriated, he contends; rather, they have prevailed, and Aboriginal influence in modern Australia has come to resemble the strange dominance of Greek culture in the Roman world that ensued once Greece had been made a subsidiary province of Rome. Of all this revolution, McLean’s book is both the new index and the chronicle: it is a tale of great transformations, where much has been lost and much finds new life. Even amid the upheavals of modernity, some quintessentially Aboriginal element survives, he argues — a spark, a true gleam, a “flash of ancestrality”. McLean turns to the most revered of Western interpreters of indigenous tradition in the mid-20th century, anthropologist Bill Stanner, to orient him in this murk. It was Stanner, in his much-studied essay collection on the Dreaming, who first put forward the appealing idea that indigenous rituals were a form of “art for art’s sake”, in which symbols were treasured for their beauty, in such a way that they preserved an essential element of Aboriginal culture even after its collision with modernity. An indigenous sensibility endures; indeed the beliefs lying at the heart of indigenous culture and guaranteed by this “aesthetic knowledge” are held on to more dearly in the face of overwhelming disruption and change.

“This is evident in the indigenous engagement with modernity,” McLean writes in his concluding grace-note. Subjection cleared the way for triumph and gave birth to new avenues of reflection. “These aesthetic manoeuvres not only incorporated modernity into an indigenous world view — they also make an art history of indigenous Australian art possible.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout