In Lisa Taddeo’s Animal, damaged women are dangerous

Joan burns the material rewards gained from selling her body like an old-fashioned millionaire who lights cigars with five-dollar bills.

Animal arrives at an interesting juncture in contemporary literature, the point where badness has been banished from the page. Not in terms of what fiction describes, since there is a panoply of wrong in the world for characters to grapple with, but in how narrators present themselves.

The rise of the “good” narrator – kind, self-aware, on the right side of the moral ledger in relation to everything, be it climate change or transgender rights – has become widespread enough to earn a backlash.

Some critics have charged these fictions with being simplistic in their moral binarism, and so boring. Others have bemoaned the contamination of a realm that should properly be judged on aesthetic grounds (is it well written?) by political ones (does it hold the correct positions?). Others still have said that to decry virtue signalling in fiction is itself a form of virtue signalling.

And then there is Lisa Taddeo, who didn’t get the memo: or if she did, decided to burn it with a pilfered cigarette lighter.

Because Joan, the narrator of Taddeo’s debut novel – follow-up to her surprise nonfiction hit about female desire from 2019, Three Women – openly describes herself as “depraved”. Joan steals, cheats and lies without compunction. She prostitutes herself, wrecks homes, drinks, snorts drugs and pops pills, and relates her actions in tones of defiant unrepentance.

Yet the other word she uses to describe herself – “survivor” – complicates matters. “A dark death thing” happened to her as a child, Joan asserts in the opening pages of the novel – an event that shaped all that followed. In truth she is a victim, one whose depravity has been a means to navigate a hostile world she moves through alone.

“I have been called a whore,” she says. “I’ve been judged not only by the things I’ve done to others, but, cruelly, by the things that have happened to me.” The story Joan sets out to tell is not intended to be exculpatory, however. She explains that the bad stuff will come first, “so that you may withhold your sympathy”. Or maybe you won’t have any sympathy at all.

In what follows, Taddeo – whose nonfiction has been centrally concerned with busting fallacies about women’s sexuality and mapping the unpredictable contours of their inner lives – takes the opportunity to dispel a truckload’s worth of them.

The resulting work might be described as #MeToo noir. It borrows the intimate first-person voice of mid-century American crime fiction – that clipped, droll, unillusioned parade of mostly masculine narrators, usually brought down by their weakness for some femme fatale – and turns the old story inside out.

Joan is that femme fatale. It was she, who, in the period just before the narrative proper begins, took an older married lover named Vic and allowed the obsessed and controlling man to provide for her, then spurned him for someone younger. When Vic follows the pair into a restaurant one night and turns a pistol on himself in front of them, the bullet loses Joan her sugar daddy and drives away the one man she adores.

Shocked by events, Joan packs her few possessions and sets out from New York for California – the traditional end of the line for Americans bent on escaping their past – where she takes an anonymous rental in the hills above Santa Monica.

It is there, Joan informs us, that a woman she has long stalked but never encountered lives. In this moment of extremity, meeting this stranger (who we readers know only as Alice) has become a matter of utmost urgency.

Taddeo does not stint in her portraiture: Joan is painted in hourglass shapes and lurid primaries. She combines blithe sexual assertiveness with an ingenue’s trembling bewilderment, acute intelligence with dumbfounding impracticality.

Toned, with a wardrobe to die for, she’s also seismically alert to male gaze and the psychology that drives it (in essence, various degrees of desire and willingness to rape women). Joan, in short, is equipped with all the psychosexual superpowers to rule the world.

If she has failed, it is because of indifference. She does not want these men. Nor does she want what they are willing to pay to have her. She burns the material rewards gained from selling her body like an old-fashioned millionaire who lights cigars with five-dollar bills.

Only now, at the age of 36, does Joan sense a waning of her powers. By making this physical move and undertaking the mission of meeting Alice, Joan acknowledges she is entering some personal endgame.

So, Animal begins as a murder mystery of sorts but evolves into a portrait of obsession that reads in part like a Lorrie Moore short story – sharp, wisecracking bar-stool sociology from a female perspective, its paragraphs built from zigzags of wicked non sequiturs – but is closer in form to one of Patricia Highsmith’s unnerving accounts of feminine fixation.

Here is Joan, having now struck up an apparently innocent friendship with Alice – a beautiful yoga instructor, somewhat younger than Joan but who recognises her immediately as a soul-twin – after she has shared the story of Vic’s suicide:

“The thing I didn’t expect was telling her about me would force me to look at myself, the way I craved the love of men who would never love me.

“At the way I could not abide women who needed me. At the way I destroyed some while allowing others to destroy me.

“I felt sick with myself and at the same time unburdened,” she concludes: “I thought I’d been honest with myself. But I hadn’t, I’d been telling myself ghost stories my entire life.”

As her relationship with Alice deepens, Joan – a narrator so unreliable she does not even believe her own stories – extends the novel’s frame back in time, to furnish an account of a childhood with that “dark death thing” at its centre, one that retains claims on the present.

Anyone who has appreciated Taddeo’s deeply researched and subtly curated nonfiction will recognise the writer’s curiosities revisited in these pages, exported and somewhat supercharged for fictional purposes. She writes well and with sharp, amoral vigour on her creation’s behalf. Joan’s language comes salted along the rim.

Less certain is whether Joan is as bad as she thinks she is. The moral shock delivered by Animal feels neutralised by the feminist impulse that inspires it.

The world has obliged Joan into depravity. Bad behaviour is her means of survival. The madness she exhibits is inspired by the pain the world brings – the murderous blows she strikes are on behalf of all women.

Which brings us back to the easy binary of the good narrator. Joan wants to outrage us with her performance of badness. She also wants us to know that she’s doing so for the right and necessary reasons. Animalholds significant pleasures as a novel, but if you want proper badness – and real art – it is Highsmith’s narrators who are truly depraved.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

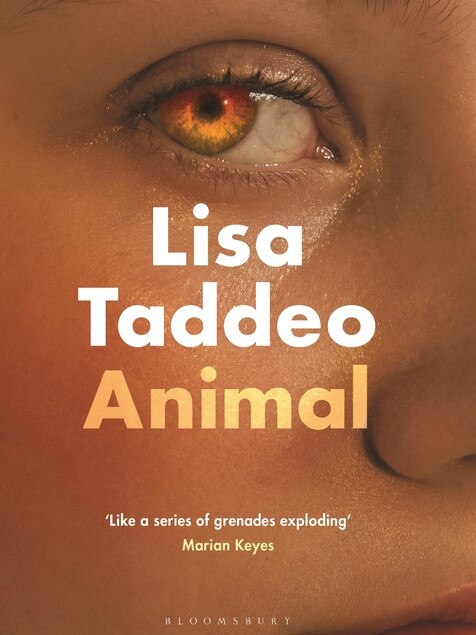

Animal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout