In China Baby Love, Jane Hutcheon tells Linda Shum’s story

Linda Shum became determined to make a difference after visiting an orphanage in China.

China is hard for the outsider. The best-laid plans can get lost in deep tangles of bureaucracy and incomprehension in this huge nation. So the sheer courage of a retired Australian primary school teacher who has spent years navigating Chinese bureaucracy to help disabled children is worth some attention.

And Linda Shum, a devout Christian grandmother from Gympie in Queensland, has had a lot of attention. She’s been interviewed for Australian newspapers, magazines and television, and she has taken it all in her stride, concentrating exclusively, it seems, on improving the plight of the kids who have dominated her life, in China and in Australia, for so many years. Publicity, after all, can bring donations.

Shum, now approaching 70, first visited China in 1998 with a Christian group. Driven by an outsized maternal instinct, she was appalled by the dirt and neglect she witnessed in the state-run orphanage in Jiaozuo, a lesser city in the province of Henan.

Determined to make a difference, she kept going back to the orphanage, and within a few years she had set up the Chinese Orphans Assistance Team, which grew to encompass foster homes and a school.

China Baby Love is the story of Shum’s life and, on an intersecting line, the story of ABC journalist Jane Hutcheon’s tangential connection to Shum and her almost obsessive drive to look after a pack of disabled kids.

These are kids with cerebral palsy, or spina bifida, or cleft palates; kids who can’t walk, kids who can’t see, kids who can’t talk, kids who were left behind or pushed away by their parents, kids who are the physical fallout of China’s now-abandoned one-child policy.

When it was in force, the policy meant most Chinese would-be parents were permitted only one child — so, naturally, they wanted a healthy, intelligent and industrious child (preferably a boy). In later years this lone child would have to care for their parents — and probably their grandparents as well.

So children who had physical or mental difficulties were often abandoned, left to understaffed institutes or orphanages to care for. They were often tied to their beds or to potty-chairs, left largely to themselves and deprived of physical affection. If they were particularly unwell, Hutcheon recounts, they could be left to die alone, untended, in notorious “dying rooms”.

These days, China is far better at caring for abandoned and disabled children, and institutionalised children are mostly warm and well-fed, although often bored: pacing, rocking, or left in front of a television, and still sometimes tied up — “for safety”.

Hutcheon, who is partly Chinese, was the ABC’s China correspondent at one time. She grew up in Hong Kong, she speaks Mandarin and Cantonese, and there is a form of abandonment in her family history — so she ticks most of the boxes needed to appreciate Shum’s motivations and the obstacles she has had to overcome.

China Baby Love is a straightforward account of Shum’s work in China, with sympathy for her various physical ailments (cancer, neuropathy, vision and weight difficulties), admiration for her sheer determination, and a certain respect for her Pentecostal religion. Hutcheon doesn’t profess to be Christian but, she writes, “I’ve discovered amazing people who do incredible things in the name of God and Jesus, and Linda is one of them”.

Although she is an ardent Christian, Shum doesn’t proselytise in China, and her overriding desire is to help these “throwaway” children, regardless of how many compromises she has to make with the Chinese authorities and how much she has to hold her evangelist Christianity in check.

I interviewed her in Jiaozuo a few years ago, and stayed in the multi-storeyed building where a number of the kids live and go to school, and I saw no evidence of preaching. The Chinese authorities have expressly forbidden it, and Shum made it clear to all foreign volunteers involved in the project that proselytising was not permitted, and repeated offences would lead to expulsion. She told me that living an honourable life, according to religious principles, was her way of demonstrating the purpose and value of Christianity.

For Shum, the kids are all-important, and everything — including the religion held close to her heart — gives way before their needs. She has pushed and struggled and wangled and negotiated, but she hasn’t given in, and she has made a world of difference to a lot of unlucky children who haven’t had much of a start in life.

As Hutcheon writes: “She has rescued around 300 children from dismal institutions and provided an education for at least 200 others who were once deemed incapable of learning.”

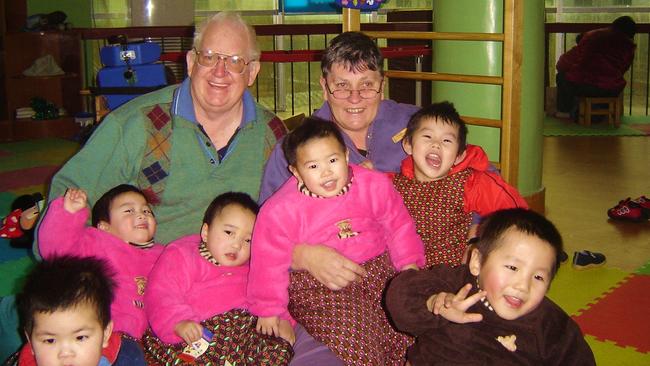

And watching Shum in Jiaozuo, with kids clambering all over her, kids in her lap, kids lighting up at the very sight of her, it’s easy to see the source of her inspiration and determination: it’s all there in the wonky smiles and fluttering hands. It’s the kids — they need her.

Sian Powell is a journalist who has lived and worked in Asia.

China Baby Love

By Jane Hutcheon

ABC Books, 320pp, $32.99