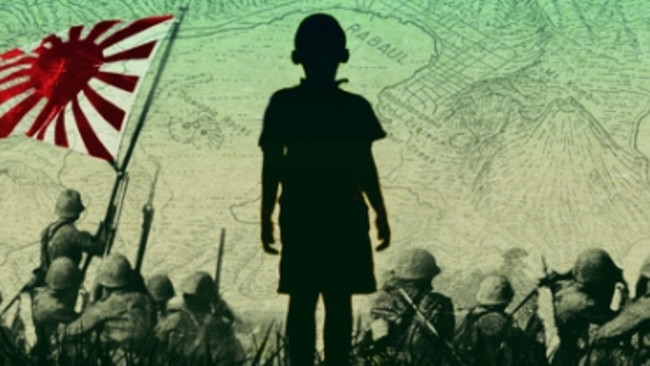

Ian Townsend’s Line of Fire: The ‘spies’ who never came back

Ian Townsend’s new book is a gripping yarn of espionage and war.

Ian Townsend’s third book, Line of Fire, a work of nonfiction, is excellent. It follows two fine novels: Affection (2007), based on the 1900 plague outbreak in north Queensland, and The Devil’s Eye, centred on the worst cyclone in Australian history.

The Queensland radio journalist and author has a talent for discovering little-known events and fleshing them out to make history come alive. His new book is a gripping yarn of espionage and war.

Townsend meticulously mined research archives in Australia, Japan and Papua New Guinea. The story he tells is as fascinating as it is tragic: in May 1942, in the tropical town of Rabaul in the then Australian territory of New Guinea, Japanese troops shot dead a group of Australians who had been convicted as spies.

One was Marjorie Manson, a dressmaker who had lived in Adelaide and Brisbane. She was executed along with her brother Jimmy, her partner AA Harvey, a friend named Bill Parker and her 11-year-old son Richard, known as Dickie.

Were they spies? During their trial it was revealed the four adults had been caught behind enemy lines with a hidden radio transmitter. Marjorie also had a concealed revolver.

Their executions occurred at the base of Tavurvur, one of the volcanoes that surround Rabaul harbour. It was the site of an earthquake in early 1941, and violent twin eruptions in 1937 in which almost 400 people perished. Indeed, as Townsend explains, this area remains one of the most seismically active places on the planet.

Acknowledging the fallibility of documents, including so-called primary sources, and the frailties and fickleness of memory, Townsend has nevertheless reconstructed an extremely intriguing historical narrative. Despite the limits of the source material, he has, in the main successfully, tried to explain how and why a working-class Australian family ended up in a hot and humid trading post, caught behind enemy lines in a brutal conflict that cost them their lives.

He also illuminates why their experiences have largely been forgotten. Part of the explanation is that a number of Marjorie’s relatives, especially her mother Phyllis, disapproved of her leaving Australia to live on a rundown plantation at Lassul, outside Rabaul, with the often unstable and grandiose Ted Harvey, a married man. As a consequence, much of the truth about the five executed Australians has not been well-known.

Townsend explores how the John Curtin government was unable to reinforce some of Australia’s small garrisons in New Guinea, while at the same time refusing to evacuate their civilian and military populations. On New Year’s Day 1942, the commander of the 2/22nd Battalion, colonel John Scanlan, issued the following order: THERE SHALL BE NO WITHDRAWAL.

Townsend documents how, in the face of an irresistible Japanese invasion soon after the Pearl Harbor attacks, more than 1500 Australian soldiers and non-combatants were abandoned in Rabaul as “hostages to fortune”.

One of the many reasons this book is so absorbing is that the multilayered experiences of these five ordinary Australians, executed in Rabaul, are part of Australia’s story and a crucial episode in our military history.

Townsend uncovers some important secrets along the way, mainly personal — including one about Dickie Manson, which I will not reveal. However, something that impresses me about the author’s approach is that he indicates where he’s more or less certain about what actually happened and where he has speculated.

He also clearly italicises conversations and dialogue he has invented. In doing so, he has tried to, as he puts it, to “keep what people said true to their character and circumstances.”. In this endeavour, too, he has also been largely successful. I like to call such books faction.

In a sad postscript, Townsend reveals that, despite her repeated efforts, which included writing to federal ministers such as Labor’s mercurial Eddie Ward, Marjorie’s estranged mother, Phyllis, never knew what had happened to her daughter, to her son Jimmy, or to her grandson Dickie. Unable to cope with such deep uncertainly, Phyllis Manson committed suicide in February 1956 at the age of 65. The grief had finally caught up with her.

Ross Fitzgerald is emeritus professor of history and politics at Griffith University.

Line of Fire

By Ian Townsend

Fourth Estate, 309pp, $29.99