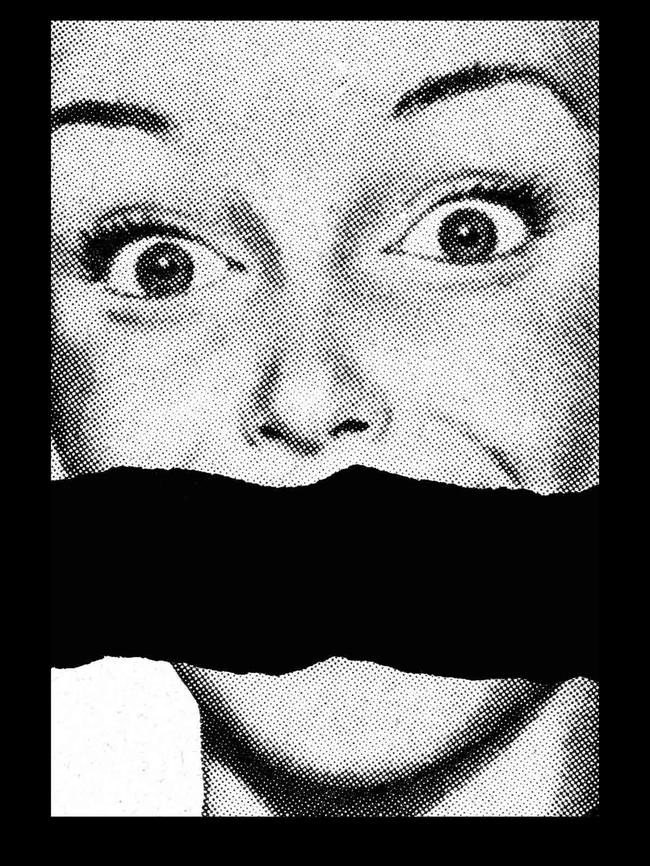

I Find That Offensive: Claire Fox blasts ‘snowflake generation’

Why are people who describe themselves as ‘libertarian Marxists’ so obsessed with the issue of freedom of speech?

A question for ideology wonks: what do the following books have in common, apart from their focus on freedom of speech and expression? Frank Furedi’s On Tolerance: A Defence of Moral Independence, Mick Hume’s Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, Brendan O’Neill’s A Duty to Offend and Kenan Malik’s From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath.

Answer: all four are by people who once belonged to the (UK) Revolutionary Communist Party, who wrote for its journal Living Marxism, and who are connected to the two entities — the online magazine Spiked and the London-based Institute of Ideas — to have emerged from the ruins of both. Coincidence? I think not!

Why are people who describe themselves as ‘‘libertarian Marxists’’ so obsessed with the issue of freedom of speech? Well, they’re libertarians for a start. You can’t be much of a libertarian if you’re content to let the state do your arguing for you. Nor, indeed, can you be much of a Marxist if you accept that the state is competent to decide what is offensive and to whom.

But what really gets the RCP veterans excited is the mindset of the modern ‘‘progressive’’. They see it as one in which censoriousness, ignorance of one’s own assumptions and intolerance in the name of tolerance are the hallmarks. For Furedi and co the radical politics of the past have deteriorated into ideological dogma and the persistent invention of fresh blasphemies.

Claire Fox is director of the Institute of Ideas and her new polemic, I Find That Offensive,is yet another grenade from the RCP crowd. Its principal target is ‘‘the snowflake generation’’, which is to say the current crop of students, especially student activists, who keep up a constant, cloying demand for their own and others’ supervision. ‘‘Safe spaces’’, ‘‘trigger warnings’’ and ‘‘microaggressions’’ are all symptoms of this trend and together add up to a new kind of politics in which the personal is less political than the political is personal.

As Fox puts it: “The way microaggressions ‘theory’ goes, if you add up minor or micro instances of even unconscious racist, homophobic, anti-Semitic, classist, ableist, cissexist speech and behaviour, all these innocuous transgressions give you justifiable reason to feel macro-aggrieved.’’

Fox identifies two main drivers of this narcissistic weepy-woo. One is identity politics, the notion that the most politically significant thing about you is your race, ethnicity, gender or religion. The other is the infantilising, safety-first tendencies of contemporary society, “a climate that routinely catastrophises and pathologises both social challenges and young people’s state of mind’’.

For Fox, it seems, both political correctness and health and safety have not only ‘‘gone mad’’ but have also combined into a single ideology.

She has a strong case, on the face of it: one only has to listen to some commentators discussing same-sex marriage to realise there is indeed a tendency to treat minority groups as dangerously vulnerable. But I also think this phenomenon has as much to do with what is learned in modern universities as it does with students’ expectations that the university act in loco parentis.

In particular it reflects the fusion of identity politics with a view of language as constitutive of reality — as no less of a weapon, potentially, than a plank of wood with a nail through the end of it. Fox touches on this phenomenon once or twice, but its significance is never analysed.

In the end I found myself both attracted to and repelled by Fox’s book, which is part of a series called Provocations. Attracted because she is right to deplore the censoriousness of parts of the left; repelled because its intention is obviously factional: it is only the left’s censoriousness that is deplored. The offence-mongering of the right — and there is lots of it around — is largely ignored. This is disingenuous. It’s also straight from the RCP playbook.

That all of the authors in my opening paragraph receive an honourable mention in the book only adds to the sense of clannishness. Fox does make some sound points. She is under no obligation to be objective but I would like to believe she was thinking independently, or making a genuine effort to do so, especially as her subject is intellectual freedom.

Richard King is the author of On Offence: The Politics of Indignation.

I Find That Offensive

By Claire Fox

Biteback Publishing, 179pp, $20