On the basis of this film, centred on an Australian war photographer, a Sydney taxi driver relocated from his native South Sudan, and their respective partners, it’s fair to say the acorn has not fallen far from the tree.

Lawrence Jnr brings an unusual and compelling perspective, through innovative camerawork, to what we see on screen. The cinematographer, Hugh Miller, filmed Lawrence’s first movie, Ghosthunter (2018), a documentary about a security guard who investigates the paranormal.

Hearts and Bones is about revealing people in emotional close-up, even when they hide it. It’s about gradually stripping off their fragile armour to show what lies underneath.

The script is by the director and writer Beatrix Christian, which is a neat family connection. Christian adapted the Carver story, So Much Water So Close to Home, into Jindabyne for Lawrence Snr.

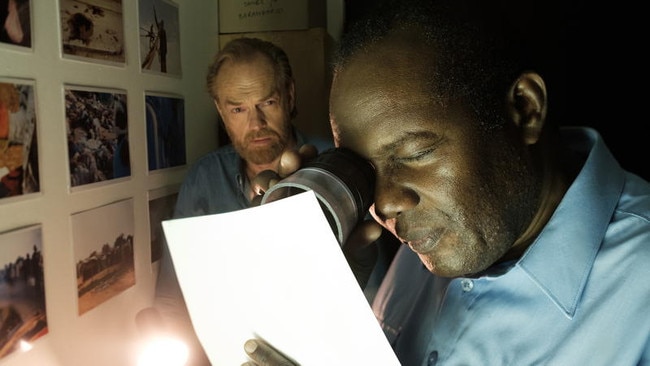

Using a camera is also how Dan Fisher (Hugo Weaving) makes his living. The opening sequence takes place in Iraq. What happens subtly, strongly, permanently affects everything that is to come.

Seeing Weaving with a camera in his hand will take viewers back to one of his early films, Jocelyn Moorhouse’s Proof (1991), in which he is a blind photographer, alongside Russell Crowe and Genevieve Picot. As it happens, I rewatched it recently, and it stands the test of time.

Hearts and Bones, shot in western Sydney, had its premiere at the 2019 Sydney Film Festival and received several nominations for the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Awards. With its planned cinema release thwarted by coronavirus, it has been made available on streaming services such as iTunes, Google Play, YouTube, Sony PlayStation, Telstra and Fetch TV. It will be released on DVD on June 3.

After that opening in Iraq, Fisher returns home to Sydney, where an exhibition of his work is being planned. He has been taking photographs — or “misery porn”, as the Border Protection Minister dubs them — in war zones for more than 20 years. It was a similar exhibition that provided Lawrence with the idea for the movie.

“I photograph what my conscience asks me to, even if it is hard to see, hard to watch,’’ Fisher says in a radio interview with the ABC’s Fran Kelly (who does the cameo).

“Hopefully the images I take enable us to say of the subject, ‘We can see you’.’’

Fulfilling this hope, however, can lead to dramatically different and unexpected outcomes, as Fisher will learn.

READ MORE: ‘A lot of people told me crazy stories’ | Alfred Hitchcock’s avian attack

A taxi driver, Sebastian Ahmed (Andrew Luri in his first acting role), hears the interview, tracks down Fisher and asks him to take photos of himself and his friends, all from Africa or the Middle East, who have escaped their troubled homelands. They have formed an informal choir.

Luri, in his early 60s, is from South Sudan. The director insisted someone from that country play someone from that country. He came to Australia on a humanitarian visa in 2003. He was driving not a taxi but a garbage truck when he auditioned for the role.

For Weaving, there was something special about working with a non-trained actor.

“I’m interested in the man. I’m interested in the real person,’’ he says. “All the experiences that Andrew has, if that can feed into the character, then it is something you can’t train for.’’

Luri’s Ahmed is the conflicted centre of this film. He is married to Anishka (Bolude Watson) and they have one young child and one on the way. He works hard and is keen to buy a dilapidated house. When he inspects it and sees the running water, his response is funny and sad.

How much his wife knows about his previous life in South Sudan is unclear. The same can be said for Fisher and his partner Josie (Hayley McElhinney). We do learn something distressing about them, something they do not talk about, and Weaving and McElhinney are heartbreakingly good in this scene.

Fisher is a man who flees in the other direction: towards the war zones. It is clear this extreme social distancing has affected him, psychologically and physically.

His hands shake. “My memory is full of holes,’’ he says. When he sees a neurologist, at his partner’s insistence, and is asked if he’s ever suffered head trauma, his answer is bleakly funny.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is in the air, for Fisher and for Ahmed. When Fisher asks his new friend if he has told his wife about what happened to him and his family in South Sudan, he responds with his own question: “Do you tell your wife what you witness while you are away?” It’s a rhetorical question. No answer is needed. This is the connection between these two men from different worlds.

It is one of Fisher’s photographs, found while organising the exhibition, that pushes this connection to breaking point. The photo is from South Sudan and Ahmed is in it. “You have opened a door to the past,’’ he tells Fisher, “that I must go through”.

This is a sad film because it is real. I admit that after watching it, the day after watching season two of Ricky Gervais’s brilliant, hard-to-watch TV series After Life, I told myself I needed to take a break and watch a comedy. I also told myself that the next time I sit down in a taxi, I need to remember the person driving it has a life that is not that different to mine.

As its title suggests, Hearts and Bones is about, in the end, how we are all just humans, complicated, flawed, hopeful and full of secrets, nothing more and nothing less.

“I tried to find a reason for what happened,’’ Ahmed says at one point, as we learn what he saw and did in South Sudan.

“There was no reason.”

Hearts and Bones (M)

Various streaming services now

DVD release June 3

Hearts and Bones is the feature debut of Ben Lawrence, son of Ray Lawrence, a director who has made only three films, all of them close to masterpieces: Bliss (1985), based on Peter Carey’s novel, Lantana (2001), based on a play by Andrew Bovell, who wrote the script, and Jindabyne (2006), based on a Raymond Carver short story.