How Vesuvius still captures our imagination

Vesuvius – the volcano that buried Pompeii – was a source of global fascination during the revolutionary upheavals of the 18th and 19th centuries.

On March 17, 1944, Mount Vesuvius erupted. For more than a week it hurled rock, spewed gases and sent a 2.5m wall of lava rolling down the mountainside. “The sound was exactly like artillery fire,” reported The New York Times. Thousands of Italians were displaced and 26 died, mostly in homes crushed by falling ash.

The disaster was managed by American and British soldiers, who had captured Naples just six months earlier.

“To look above the mountain tonight,” wrote one GI in his diary, “one would think that the world was on fire.” And so, in a way, it was.

What the soldier witnessed was the last (or latest) eruption of Vesuvius, now dormant. The catastrophe of 1944 was certainly not its only eruption to coincide with portentous world events.

Vesuvius is best known for the eruption of A.D. 79, which entombed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. There was another terrible eruption in 1631, which killed 4000 people.

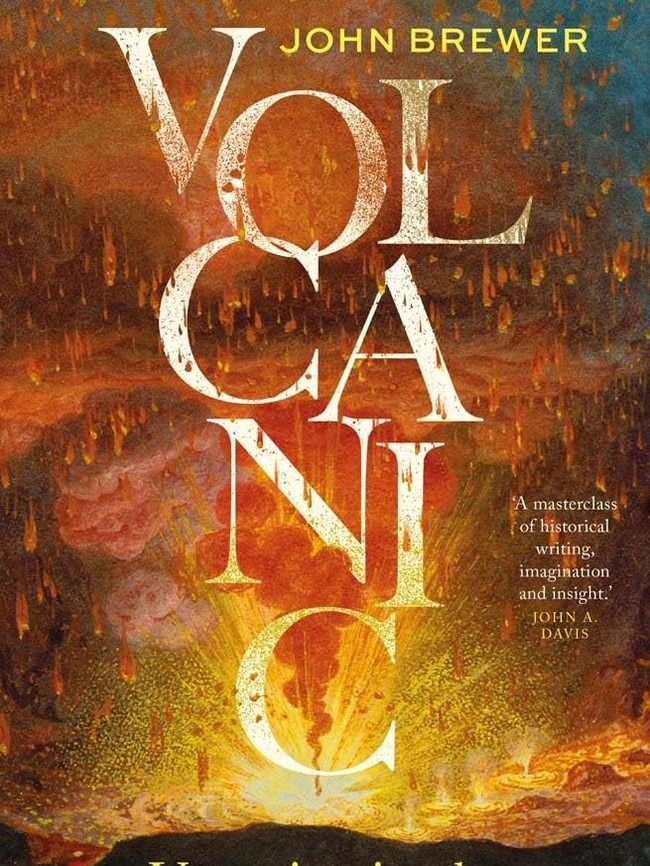

In Volcanic: Vesuvius in the Age of Revolutions, a splendid work of historical archaeology, John Brewer refers to these storied disasters, but his own narrative centres on the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period when the volcano was unusually active and an object of global fascination. The French Revolution and its unsettled aftermath – a world-shaking era in many respects – made Vesuvius into an emblem of cataclysmic transformation.

Brewer, an emeritus professor at the California Institute of Technology, has written previous works on the cultural history of art connoisseurship, travel and tourism. Volcanic uses these topics to explore the ways in which particular generations of Europeans and Americans experienced the world’s most fabled volcano. The subject is rich, for Vesuvius was not one phenomenon but many.

It existed as a natural catastrophe, a place of scientific discovery, a subject of art, a destination for travellers and a contested political site. After the excavation of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the mid-18th century, Vesuvius became, as well, an object of tragic historical reflection.

Volcanic is a long and somewhat peripatetic book but compulsively interesting. Its chapters explore literary reactions to Vesuvius, artistic representations, the evolving science of vulcanology, the revolutionary political context of Europe and Naples, and shifting patterns of travel that brought thousands to the mountain.

Brewer writes as a literary and art critic as well as a historian – and he writes beautifully. His prose contains neither the academic jargon nor the weary cynicism that deaden so much cultural history. He treats the actors in his history humanely. Their longings, curiosities, obsessions and fears are presented with an almost wistful empathy.

Who are those actors? They vary. Brewer skilfully exploits the chance survival of one of the visitors’ books kept at the hermitage of San Salvatore. Built on Vesuvius’ mountainside in the 1650s, the hermitage served as a rest stop and inn for visitors, who could refresh themselves with a (pricey) meal and a glass of Lacryma Christi (or Tears of Christ), a wine made from grapes grown on Vesuvius.

This particular visitors’ book dates from the 1820s, and in it, alongside names and nationalities, are inscribed individual reactions to Vesuvius: impromptu poems, complaints about guides and food, classical quotations, lines of reflection. Inscriptions could be crass or refined, high or low. The garment maker Robert Pike of London wrote out an advertisement, claiming that his padded trusses were a “Capital thing to wear ascending the mountain’’. Some reached for saccharine sentiments. Wrote one visitor next to the name of his travelling companion (presumably on a subsequent trip alone): “My friend, I burn to see you again and to press you to my heart.”

The visitors’ book serves as the spine of Brewer’s study, revealing “the vicissitudes and pleasures of the journey up the volcano’’. But he ranges far beyond this source into printed works, diaries and letters. He quotes, for instance, the remarkable reaction of Maximilian, brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph.

The volcano, he wrote in 1851, was an overwhelming “remnant of chaos” from a time when the “race of sinners had not yet made an impression on Earth” and “when the soft mess of clay was not yet animated by the breath of the Most High … As God created, so He will destroy.”

The hermitage and the mountain itself witnessed nationalistic brawls, tumultuous love affairs, tragic accidents. In a disorienting and vivid setting, social mores were often bent. Brewer describes one group of diplomats and scholars who descended into the volcano’s very crater. “The heat was so fierce they were forced to strip naked, while they dined on a picnic of pigeons they roasted in the lava streams.” At least one visitor died by suicide by hurling himself into a steaming volcanic vent.

Brewer devotes individual chapters to important naturalists, such as the eccentric French nobleman Déodat de Dolomieu, a pre-eminent volcanologist who accompanied Napoleon to Egypt, barely survived the Terror and wrote an important book on mineralogy while imprisoned by the King of Naples. His many trips to Vesuvius were serious and scientific rather than diverting or romantic. A wonderful chapter on the local guides at Vesuvius culminates with the theatrical Salvatore Madonna who presided as “chief guide” at the volcano for decades, created a family monopoly of the business and became something of a European celebrity.

One narrative thread of the book is the transformation of the very process of visiting Vesuvius. Earlier visitors travelled by donkey, hiked up the mountain for hours and were then hauled through the ashy sides of the cone by rope-wielding guides. The experience could leave travellers exhausted and filthy, their shoes shredded by volcanic rock, but it lent a sense of adventurous moment to the journey. Eventually donkey paths were replaced by roads, and the “human skills and labour of the guides were replaced by new technologies and modern improvements,” Brewer writes.

By 1880 a funicular railway bore tourists to within a few hundred metres of the volcano’s summit.

Current enthusiasts for Vesuvius can view, on the internet, remarkable newsreels of the 1944 eruption. Our ancestors relied instead on oil paintings and travel writings for their sense of the volcano’s enchanting dangers. Or, by the thousands, they attended the panorama exhibitions that became popular in postrevolutionary Europe. Cylindrical paintings depicting natural or historic scenes, panoramas “transfixed” viewers in a “magic circle” (according to Alexander von Humboldt).

From distant Dublin or Berlin, panoramas might depict Vesuvius in eruption or offer a vista of the volcano from the Bay of Naples. In the aftermath of revolutionary trauma, Europeans developed a taste for vitalising experiences of ungovernable, sublime nature. Commentary about Vesuvius, often from pre-eminent figures – Shelley, Chateaubriand and others – reflected this sensibility.

Goethe recorded the breathtaking sight of Vesuvius, in his case observed from the safety of the Neapolitan royal palace in the company of a young Italian duchess: “The mountain roared, and at each eruption the enormous pillar of smoke above it was rent asunder as if by lightning, and in the glare, the separate clouds of vapour stood out in sculpted relief.” Against the molten lava and the full moon, his aristocratic companion “looked more beautiful than ever’’.

Volcanoes – Vesuvius chief among them – served as a ubiquitous political metaphor, as well, capturing the memory of past upheavals and the fear of future ones. Napoleon himself, on seizing power in 1799, informed France’s Council of 500: “Representatives, you are not surrounded by ordinary circumstances. You are sitting on a volcano.” A popular republican play of the era, The Last Judgement of Kings, paraded monarchs and popes on stage to be satirised and then vengefully consumed by an elaborately enacted volcanic eruption.

Radicals understood the volcano to represent creative destruction and upheaval. Conservatives, Brewer notes, preferred to use Vesuvius’s buried sites as symbols. The excavated artefacts of Pompeii and Herculaneum evoked “feelings about history, time, rupture, death, loss and nostalgia”. More vulgarly, conservatives could understand the events of A.D. 79 as divine judgment on the Romans for their paganism and sexual excess.

Revolutionary politics and Romantic culture thus “decoded” Vesuvius for human audiences during this period. Art forms old and new were deployed to represent the volcano and emerging sciences marshalled to explain and predict its behaviour. There was a compulsive desire to make Vesuvius a “regulated object of human contrivance,” Brewer writes.

These ephemeral human efforts constituted a mere moment in the unimaginably long natural history of the volcano. It is a history, Brewer says, that “does not fit into a reassuring story of human progress”.

An absorbing study by a master historian, Volcanic chronicles our fleeting attempts to comprehend, control and shape an unmasterable force of nature. The book’s details can be lightly diverting, but its broader themes are existentially humbling.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout