How the people of Yirrkala changed the course of Australian democracy

Sixty thousand years. That is how long the Yolngu people believe they have lived on lands they call Yirrkala, in northeast Arnhem Land. Sixty years ago, local tribes were told they did not in fact own that land. So a plan was hatched.

Sixty thousand years. That is how long the Yolngu people believe they have lived on lands they call Yirrkala, in northeast Arnhem Land.

Sixty years ago. That is how recently local tribes were told they did not, in fact, own the land and therefore they would have to make way for bauxite mining leases that had been granted to a private company. They were bewildered and wished to protest, but how?

In July 1963, a plan was hatched: local tribes would petition the Australian government, in English and in their native tongue. They would explain to sitting members of the House of Representatives in faraway Canberra the importance of the land, and gently but firmly request a seat at any decision-making table.

For assistance the tribes turned to the white superintendent of the mission at Yirrkala, Methodist minister Edgar Wells.

In a history-making moment his wife, writer Ann E. Wells, agreed to type up a petition on her old Remington typewriter. Nine men and three women from Yirrkala signed that petition. Twelve copies were made, four copies of which were pasted on to bark cut from local trees. Elders painted the borders with ochre pictures of turtles, fish, goannas and bandicoots, and sent them on their way.

The Canberra Times described their arrival in Canberra as “novel” – but they were far more than that. The petitions stated that the land to be mined for bauxite “has been hunting and food gathering land for the Yirrkala tribes from time immemorial”.

While not fully realised at the time, this was the first formal assertion of land rights by Aboriginal people to the Australian parliament, and therefore the first step in what would become a nationwide campaign for Indigenous land rights that would ultimately result in royalties being paid.

“It was momentous,” Melbourne historian and new National Museum of Australia council chairwoman Clare Wright says.

Yet the story had hardly been told.

Wright knew a little about it because her interest, as a historian, has largely been on the expansion of human rights to excluded groups in Australia. For example, she has written a complete history of Eureka; and she has written a history of the successful campaign for women’s suffrage. She had seen one of the bark petitions on display at Parliament House. She also has a connection to the land at Yirrkala: in 2010, her then husband, Damien Wright, asked her to move there.

“Damien is a craftsman, and one of his tables had attracted the eye of Dr Yunupingu, who was born and lived his whole life in Arnhem Land,” says Wright. (Since his death last year, Galarrwuy Yunupingu has been known in print as Dr Yunupingu; his full name is used here to identify him to readers as a former Australian of the Year and land rights campaigner, whose brother was the lead singer of Yothu Yindi, whose song Treaty was also part of a campaign for land rights.)

Yunupingu was interested in the idea of sustainable enterprise for his community, and he asked Damien to help.

“He asked if he could bring his family – we had three young children, one in prep – and I knew it would change my life, and it did,” says Wright.

The couple found a home amid the oystercatchers. They enrolled their children in the local school. For Wright, the experience was, at first, as discombobulating as the idea of a House of Representatives must have seemed to the Yolngu: she was in Australia yet unable to speak the language or understand the etiquette and expectations.

“Nobody had adopted me, and that had to happen before I could really be immersed in life there,” she says. “If you are on community for any length of time, essentially you need to be adopted by somebody because you don’t make sense otherwise. Once you are adopted, you are related to everybody, and suddenly everybody you speak to knows what kinship name to call you and what the reciprocal relationships are.”

Wright had been living locally for about a month when Dr Yunupingu’s fourth tribal wife, Valerie Ganambarr – a woman “so beautiful I could barely take my eyes off her” – offered to adopt her. “My children had become friends with Valerie’s children at school, and her children had been coming home after school with me. After a few rounds of that, she said, has anybody been adopting you yet? I said, no, not yet.

“She said, ‘I am adopting you. You call me yapa – sister. I call you yapa, and your children, I call waku, and you call my children waku.’ And her grandchildren would become my grandchildren, and so on. And because she was Dr Yunupingu’s fourth and youngest wife, he was mostly living with her, and because I was now part of that household, I spent a lot of time with him, talking.”

Wright says she had not, at that point, committed herself to writing a history of the bark petitions, in part because she had so much other work to do. It wasn’t until she and Dr Yunupingu started talking about mining history that she realised there was a story there to be told and that the Gumatj leader wanted her to help tell it.

Besides being a historian, Wright is broadcaster, documentary maker, podcaster and author; she’s also a professor at La Trobe and, in 2020, she was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia in the Australia Day honours list for services to literature and to historical research. She has plenty to keep her occupied, yet the story of the Yolngu people did not leave her and, even after resettling in Melbourne, she returned to the community that had adopted her many times. In the wet season of 2019, with her children now grown up, she attended the funeral of Dr Yunupingu’s second wife, Margaret. Dr Yunupingu was, by then, in poor health. He had lost a leg to diabetes and he was confined to a wheelchair.

“We began talking,” she says. “And over time I asked, and he gave me permission, to write the story of the bark petitions.”

Dr Yunupingu had been just 15 years old when the petitions were created, but he knew many of the signatories. Wright says she was driving him to the ceremony grounds when she shyly asked what he had called them. He was silent for a moment, and she wondered whether she had transgressed.

Finally, he said: “Naku Dharuk.”

Naku – Nah-koo, for the Darwin stringybark.

Dharuk – Dah-rook, for message.

She believes it was the first time “a white fella” had ever asked the community what they had called these special artefacts, and she knew then that her decision, to shelve a planned book about mining in Australia in favour of a book about the bark petitions had been the right one.

“It was a story that needed to be told and that many Yolngu elders wanted to be told while people who knew about it were still alive to help tell it,” she says.

She hit the phone books, trying to find descendants of those who had been on the mission when the petitions were created.

“All historians hope for a eureka moment,” she says. “I was hoping to have mine.”

She knew the Wellses had had a son, Jim, “so I was going through the phone book, cold-calling people, asking if they were related to Edgar and Ann, until somebody said yes. He was still alive, living in Melbourne. And my next question was: do you have anything of theirs? And Jim said, I have everything.”

She had to wait for another break in the Victorian lockdown before she could go to his house to have a rummage around, but the trove was “every historian’s absolute dream, original source documents, beautifully cared for, that nobody except those that had stored them had seen before”.

Jim showed Wright the typewriter on which the original petitions had been typed before being pasted on to bark.

She knew it was precious, but something more precious was still missing. Two of the original petitions were on display at Parliament House in Canberra, and one was at the National Museum of Australia (of which she last month, by happenstance, became chair). The fourth was apparently missing.

Piecing together archival fragments and oral testimony, Wright discovered that it had been given to a man called Stan Davey, who had been secretary of the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement in the 1960s, and integral to the Yirrkala people’s protest, as a way of saying thank you for his passionate work on behalf of Indigenous people. Davey had given it to his first wife, Joan McKie, who had taken it with her to Brisbane, then Derby in the Kimberley, after the couple separated.

“This wasn’t a case of it being stolen, or taken, there was not colonial stealing or anything like that, but I needed to know what happened to it,” says Wright. “I had to find Joan, but how do you find a missing 90-year-old?” She laughs, then continues: “On Facebook! That’s how I found her. I sent her a message. Then I called her, and I explained who I was, and I said, do you happen to have the bark petition? She said, yes, it’s on my wall. I’m looking at it right now.”

Wright’s heart leapt.

“It was delicate, but I had to ask,” she says. “I said, what are you planning to do with it? And she said, I was planning to hand it down to my daughters. And then she said, why? Have you got another idea? And I said, actually, I think it would be incredible if it could return to country. I think that it would mean an enormous amount to the community, if it could come home.”

McKie agreed to discuss it with her adult daughters, and all immediately agreed it must go home.

Wright would go on to facilitate the return of the fourth petition to Yirrkala. A local elder, Yananymul Mununggurr, whose father was one of the original signatories, has described it as a “lost treasure … coming home to us”.

With the missing artefact found, Wright, who presents in person as tiny, spirited, tattooed, brilliant and driven, felt she had all the pieces she needed to tell “the whole story” of the bark petitions. But could she do it? As a historian, she was conscious of the context: she is a white woman, and this is a land rights story.

“I’m not fearful (of people saying it’s not her story to tell) because I know in my heart that I have done this the right way,” she says. “I have permission from the community to tell the story. I have earned their trust. And I know that I have behaved ethically by the Yolngu people and their cultural practices. And I would also say, when I was writing the Eureka book (The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka) and the suffrage book (You Daughters of Freedom), people would say, ‘Oh, you write women’s history’ and I would say no, I write Australian political history with the women put back in.

“And this is the same: it’s not solely a First Nations story, it’s Australian political history with the First Nations people put back in.”

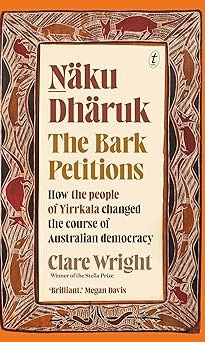

Wright pushed to have the Yolngu name for the bark petitions included in the title of her book: Naku Dharuk The Bark Petitions: How The People of Yirrkala Changed The Course of Australian Democracy (Text Publishing). The book has been endorsed by Indigenous academics, among them Harvard University’s Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser chair of Australian studies, Megan Davis; University of Technology Sydney professor Larissa Behrendt; and activist Thomas Mayo, who says it’s a “lesson in diplomacy”.

Wright says she came to know Davis during the campaign for Yes in the Voice referendum. They collaborated on making the You’re the Voice advertising campaign.

“Yes, I became an activist,” she says. “I took an active role in a political campaign that was important to me. I thought constantly during that campaign of what it would mean to my yapa (sister) and the children and grandchildren of the Yolngu people, to have a voice to parliament enshrined in the Constitution. A voice – consultation – was, after all, what the bark petitions called for 60 years ago.”

The book is being published just as Wright takes up her new role at the National Museum of Australia. She says federal Arts Minister Tony Burke asked her to join the board two years ago because he wanted a historian: “He thought it was crazy that the board of the national museum” did not include a historian.

She supports the federal government’s national cultural policy, including its First Nations First pillar, and she rejects the idea that history can or should be neutral, saying: “It’s always going to be about who gets to write it, and what they decide to write about, and from whose point of view.”

Wright acknowledges the reality of Australia’s “history wars” but says: “I hope they are now more skirmishes than wars because most historians would agree, I think, that we have to keep putting people back into our national story, where they’ve been ignored or taken out. And I would argue that history doesn’t have to be triumphalist and celebratory all the time. Truth-telling – which is really just another word for history-making – is hard. If we don’t tell the whole story, it’s like a family pretending that everybody is doing well, that nothing’s ever gone wrong, that nobody’s unemployed, nobody’s unwell, nobody’s divorced, nobody has jealousies and rivalries, we’re just all courageous and harmonious and perfect. Show me that family, and I’ll show you a family that is probably deeply dysfunctional and certainly in denial. It’s the same with history. We have to tell the whole story, even if it’s uncomfortable.”

Wright’s book is dedicated to Yolngu elders, past and present, and to her yapa Valerie Ganambarr. She will travel 3000km to launch it in community, where she will again get to see the once-missing petition, which is on permanent display at the Buku Larrnggay Mulka Centre.

Which raises another question: while certainly beautiful, is it an artwork? Or, more accurately, a deed or entreaty?

Wright says it is all those things, but also a symbol of pride, created by people who believed in their bones that they had sovereignty over the land on which they lived, who were prepared to come forward to ask with dignity for a seat at the decision-making table. They are asking still.

Naku Dharuk The Bark Petitions: How the People of Yirrkala Changed the Courseof Australian Democracy (640pp, $45), is published on October 1 by Text.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout