How the cranky, silent women of the past paved the way

Grandmothers are supposed to be cosy creatures. Mine wasn’t. But I now understand how recent and how fragile my freedoms are, and how much her and her generation did for us.

Grandmothers are supposed to be cosy creatures, all scones and big warm hugs. Mine wasn’t – she was cranky, frowning, scary. My mother’s stories portrayed Grandma as an unloving bully. “Why did my mother never love me?” Mum would ask, and I had no answers.

But when I set out to write a book about my mother I came to see Grandma in a different light. Yes, she was cranky, but like most women of her time and place, she had a lot to be cranky about.

Dolly Maunder was born in 1880 into a poor farming family in northern NSW, her forebears illiterate men and women from England who’d ended up in Australia as indentured labourers or convicts.

Women from higher social levels sometimes left journals and letters, but women from Dolly’s background didn’t have the time, or in many cases the education, to write about their lives. Because it was only the top lot who left anything of themselves behind, our picture of the past is skewed into a stereotype of dainty women sitting around doing a spot of cross-stitch and dithering about which man to marry. But women like Dolly were the vast majority. I wanted to put them back into that picture.

For a woman born clever and energetic any time before the 20th century, her options were cruelly limited. Grandma wanted to train as a teacher – one of the very few jobs open to women – but her father said “Over my dead body!” A daughter going out to work would shame him. People would think he couldn’t support his family. Blocked from earning her own income, she had no choice but to marry.

That would have been that for Dolly Maunder, except that, the year she was born, the men in far-off Sydney who ran things had passed a new law saying that every child had to go to school between the ages of six and 14. It was an upheaval that changed everything for families like the Maunders. Overnight Dolly’s father had lost the free workers his farm depended on. For him, compulsory education must have seemed an outrageous government overreach.

But for Dolly, those few years of schooling turned out to be her ticket to freedom. When she and her husband went seven years without a crop on their farm, they could walk away. They had just enough schooling to go into business, buying and selling country pubs. Dolly had a restless entrepreneurial spirit and thanks to her, they made a fortune (then lost it all in the Depression).

Dolly was the dynamo in the marriage, that was clear. But she had no power and no rights. Every lease, every licence and every title deed was in Bert’s name. Every good idea had to meet with his approval. Bert turned out to have a roving eye, but if she’d left him, she’d have lost her children and been penniless.

I could piece all this together from family stories and research. What had vanished was how she thought or felt about any of it. Women like Dolly were on the receiving end of a lot of guff about “a woman’s place”, and it’s easy to assume they believed it, but did they really?

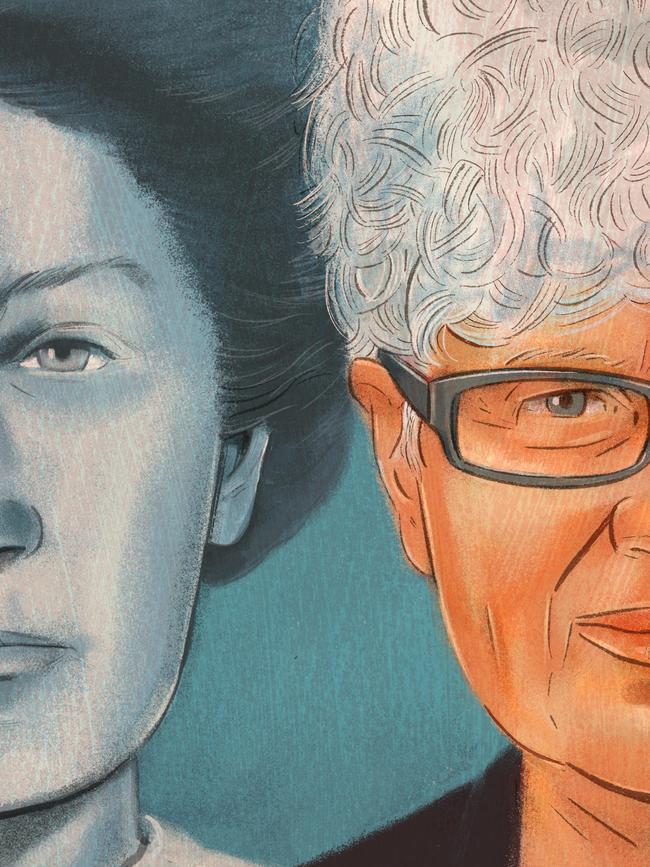

There are only three photos of Dolly that I know of. One’s a snapshot of four middle-aged women holding golf clubs, one’s a wedding photo (the cranky look I came to know is already in place), and the third is a studio portrait taken a few years before she married. It’s typical of its time: the photographer has provided the posh classical landscape of columns and urns Dolly sits among, the complicated dress she’s trussed up in, and the book she’s pretending to have just glanced up from. Among all that paraphernalia is her small, unsmiling face, stiffly holding the pose for the long exposure. It’s a moment from an utterly foreign world. Dolly, like the women in all those old photos, seems a creature from another species. I despaired of ever entering her world and telling her story.

But when I zoomed in past the ye olde stuff so that all I could see was her face, Dolly suddenly became real. A woman stared at me who I could pass on the street or even see in the mirror. She was looking straight at the lens with an expression that could be sceptical, or even faintly amused – at the antics of the photographer behind his black cloth, and at herself sitting there dressed up as something she wasn’t. This wasn’t a creature from another species. It was a woman I could feel comradely towards.

Squeeze any of us into those ridiculous clothes and none of us would be quite human, either. In the photo the only thing that belonged to Dolly was her face, and that was the talisman I kept coming back to when writing the book.

Gazing into my grandmother’s eyes, I felt she was urging me on. “Yes, tell my story! Let me not disappear! It doesn’t matter if you get it a bit wrong!” Of course, this is the kind of magical thinking that keeps writers going. The fact was, I was going to have to imagine my way into the world behind Dolly’s face. Put bluntly, I was going to have to make a lot up.

Did I have the right to do that? And even if I did, could I do it in a way that didn’t just impose my modern sensibility on to Dolly’s time and place? I still don’t know the answer to those questions, but I decided it was worth trying. Dolly was unique, but she also represented that vast crowd of women whose lives had vanished. Telling the story of my own grandmother was to tell the story of countless others as well.

I’ve come to think of what I’ve done in writing Dolly’s life (and what many biographers, historians and other novelists are doing) is like what scientists do when they re-introduce an almost-extinct species into a landscape. Without that species – those silent stories – we can’t properly understand the ecosystems of the foreign country of the past, or the present that’s been shaped by that past.

Dolly was born into a life of frustration and injustice, and it made her that cranky old woman I knew. But she made sure that her daughter – my mother – had opportunities she herself never had. In her turn my mother opened up worlds of possibility for me.

Now I’ve walked in Dolly’s shoes for a time, in writing her story, I understand how recent and how fragile my freedoms are, and how much those silent women did for us.

Kate Grenville is the award-winning author of 15 books. Restless Dolly Maunder, 256pp, published by Text, is published on July 18.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout