How love became the miracle of my mortality

When I tell people the story of my misdiagnosis they are furious, and urge me to sue for malpractice. But I refuse to face the challenges ahead of me filled with bile.

I have two questions for the oncologist when we meet for the second time: the first, which I want to get off my chest, is whether an earlier diagnosis might have made a difference. By difference, I mean, between life and death.

I know it’s a question he won’t or can’t answer. He hints, emms and ahhs, and says something about my intelligence being able to answer that myself. I nod, and as a fellow Jew, I quote from the Talmud: hamevin yavin – the one who understands, understands.

And I understand enough.

When I tell people the story of my misdiagnosis – for months, despite being in terrible pain, I was told that I had no more than an irritable bowel, when it was the deadly pancreatic cancer – they are furious, and urge me to sue for malpractice.

But I refuse to face the challenges ahead of me filled with bile.

The second question is harder. I ask him to tell me honestly what the prognosis is. He says 50 per cent of people with pancreatic cancer live up to a year.

“Six to nine months on average,” I correct him, based on my extensive internet research.

The scales of life and death have dramatically tilted.

In the Bible it says no man knows the time of his death, and that’s true, but there is an unbridgeable chasm between one who has a clear vision of the horizon of death to which they are fast approaching, and those who know it as an abstract truism that we are all going to die one day.

The more I yearn for the ordinary routines of life, the greater I feel its impending loss. There is no way to escape awareness of my tumours. Even as the physical pain lessens when the new chemotherapy regime starts to work, a different kind of pain sharpens.

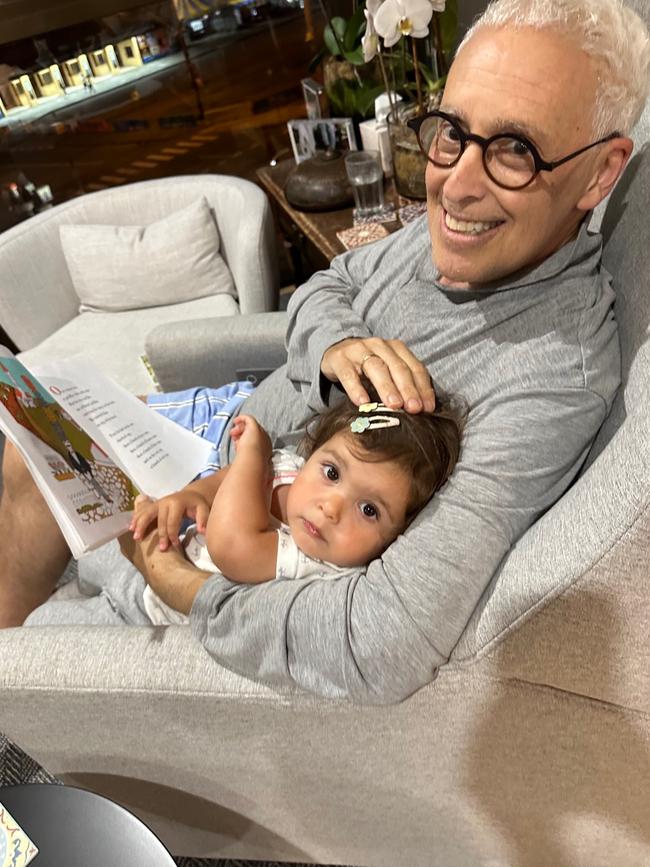

My daughter, Melila – her name rhymes with tequila; she is the miracle, at the end of 22 rounds of IVF – is 10 months old, and she has moved quickly from commando crawling to standing upright. Her mouth fills with teeth and she learns to count, at first the even numbers, leaving us to prompt her with the odd numbers. Soon she adds the words “tablets” and “hospital” to her vocabulary.

I think of the way she bangs on the bedroom door when her mother, my wife, Michelle takes her out in the morning and lets me sleep in.

“Dadda, Dadda,” she cries, and bursts into the room.

Is that how she’ll be for the rest of her life, not only as a baby but also a teenager and adult?

■ ■ ■

I make an appointment with an acupuncturist. Speaking in a Chinese accent, his words sound banal, but in the context of my cancer they impact me profoundly.

“Your baby daughter is your heart. Your angel. She will heal you. The subconscious is very important. You must smile and believe,” he says.

I carry his voice in my head, like Mr Miyagi in The Karate Kid.

“Remember. You can live with cancer. You are not a statistic. A tree can live with illness but we kill it when we try to cut out the disease with an axe. You are an ancient tree. You must stop thinking you are dying.”

My embrace of his words might be an act of desperation. I know the statistics but at the same time no person is a statistic. Most importantly, the acupuncturist treats me as a person, an individual with cancer. He takes the time to learn about the people in my family circle who love me.

All this contrasts with most of the oncologists and doctors, who barely know my name without looking at my latest tumour markers on the computer screen. They treat me like someone who makes it on to the rollcall:

Name. Date of birth. Address.

And there is my prognosis. I don’t want months. I want 30 years. All my positive vibes and people’s prayers can’t change the inevitability that the chemo will one day stop working its magic, and abracadabra, the tumours will zip through my body. I turn to my doctors and beg them to find me a trial – here or overseas in the United States.

The response: It’s unlikely you’ll be eligible for a trial and, in any case, phase one or two trials will unlikely impact your condition.”

“I don’t care,” I answer. “It’s my only hope.”

We all know in our heads that one day we will die. Naively, we believe that such knowledge somehow prepares us for the dreaded moment when we learn that the end is close.

It’s difficult to explain what it’s like to believe that it’s unlikely that one has a future.

I quickly learned that what is important to me narrowed into a series of concentric circles at whose core lies my family, followed by close friends.

Almost all my thoughts and actions are for my wife, my children (three with my first wife, Kerryn, who died of cancer in her 50s; and Melila, with my second wife, Michelle); my mother and my grandchildren, and the pain of witnessing their grief and carrying mine.

In my new inner world of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, nurses and oncologists, I have become unresponsive to almost everything I once cared about passionately – the political state of the world, ideological debates, the doomsday news cycle fed to me by the second on social media. The only news that preoccupies me is my tumour markers. My world has shrunk and pushed the things that mattered most to me out of my mental frame.

As I stare into the wilderness of knowing and not knowing my future, my focus is on injecting as much of “me” as I can into the people I love. Now is not the time to belatedly try to fit in all the things I always wanted to do, as if in the 11th hour you can define who you are and the life you have lived. My struggle is to get out of bed and to play with Melila, or to see my grandchildren and walk down the street with them. I barely recognise my disfigured body. I have shaved my hair, lost my muscle weight, lightened my olive skin.

Who am I?

Have I been Mark Baker? Truthfully, authentically myself? True to myself? I don’t even know how to construct a narrative of my life outside of the bits and pieces of my years.

My friends have noticed the way my interests and projects have shifted each decade of my life. Drained of the daily toil and deliberations that made their realisation possible, they now feel like a bronze statue marking my legacy. My academic career. The books I have written. The Jewish journal I edited. The organisation for global social justice I founded. The synagogue I established and led. My role as director of Jewish studies.

I find myself drawn to those novels and authors from my final years at school, perhaps in a futile attempt to relive and return to those years where the future lay ahead of me. Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter, which reflect on faith and sin, and also death. Rather than the frustrating chase to keep up with contemporary books, I want time to reread Sons and Lovers, The Go-Between and Margaret Drabble’s The Millstone. And then there are the Russian novels I studied in their original black-spined Penguin editions at university. Do I have time for Anna Karenina, War and Peace, the books by Turgenev and stories by Chekhov?

Does anyone have time?

And what of the classics unread on my shelf: Michelle’s copy of Middlemarch and Remembrance of Things Past? Do I have time to read all these books in my lifetime? Would I ever have read them if I’d lived till old age?

My musical taste has shifted to mirror my literary preferences. I’ve returned to classical music, though I still love the folk singers of the politically conscious decades: Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, James Taylor. In my bedroom during my university days I hung a large poster of Bach above my record-player. I now lie in bed at night wearing AirPods and listen to everything Bach, especially his Cello Suites; Mozart’s Requiem; Strauss’ Metamorphosen and Mahler’s Adagietto from Symphony No.5, used to great effect in the movie rendition of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice.

My beginning is my end. A child as an adult. An adult as a child. Riding the circle game until I am gone, leaving the detritus of my life to be picked up and told, and retold, by those who summon up my name. Dust to ashes. Ashes to dust.

The clock is ticking, forwards and backwards. Soon, time will stop for me and the putrid water from which I was formed will merge with the worms and maggots in my grave. I will be the one person at my burial who doesn’t hear the thud of earth landing on the coffin or note who was present (and absent) from the funeral of the late Mark Baker, to which he added the middle name Raphael, after his oldest ancestor and the angel of healing.

Who is Mark Raphael Baker?

■ ■ ■

I drag myself out of bed. Michelle helps me dress Melila. I want to stroll to the sea, taking the same route I used to take before I was diagnosed. All we can hear is the warble of morning birds. I continue towards the beach and wait for the traffic lights to show the green walking person. I feel jealous of the early morning joggers. I used to run a five-kilometre stretch along the beach a couple of times a week. My dream from before Melila was born was to run with her in a sturdy jogger pram.

Shattered dreams, when you are facing death, become bucket lists, and this one edges high on the list.

My older kids buy me a second stroller for Melila, a three-wheeler designed for long-distance sprinting. But when I try it, I can barely accelerate for more than 30 seconds. My neuropathic feet and legs are too weak to carry me, and my breath is too short to speed up. I cross off the item on my bucket list. At least I tried. Give yourself a tick. I take Melila to the edge of the pontoon and point at the seagulls dipping into the bay. I point beyond, past the horizon, at the endless ocean. Somewhere on a distant island the water splashes along the edge of the Earth. I imagine myself travelling there on a boat, through night and day to where the wild things are.

On the other side I see a mirror image of myself standing on the edge of the railing with Melila.

I stare out at the ocean again and tears well in my eyes. I bend down and kiss Melila on the cheek.

“Dadda’s okay,” she says to me.

She reaches out and wipes my tears. How does she know to comfort me? I am overwhelmed by how much I love this world. Perhaps because death has visited me so often these past years – my father, my first wife, my brother – I have skipped a stage of mourning.

Denial.

I have an exit strategy. The survivors are the ones who will suffer.

I have no illusions.

The high odds are that by the end of the year – earlier? – I will no longer be here. I don’t know when that time will come. Right now, I feel a life force bleed in me, my soul breathes through me. My fatigue wants to fight it, but I say to myself, I can fight back. I don’t have to live in the Kingdom of the Ill. I don’t have to accept death.

I can live with my tumour, the healing treatments of chemotherapy, the dice cast against me. I can also live with the irrational hope that drove Michelle to continue with IVF cycles until we created our miracle baby. I don’t expect a miracle, but I can act as if it will come, just like love came crazily in my path and I picked myself up from the ground so that Michelle would stand by my side for the rest of my life, forever.

There is no rational reason, but I also want to stand on my head. After I was diagnosed with cancer, Michelle organised a private yoga class at home on my birthday. I loved it so much that the teacher returned each week, then twice a week. It’s the only thing that gets me out of my head and allows me to forget that I have cancer, this single hour on the mat.

I tell the teacher that my aim is to stand on my head and see the world upright – my upside-down world.

I go down on all fours on to the pier. I place my arms outwards and kick my feet up. They fall back on the ground. I try again. The same thing. On the third attempt, I feel my body rise, the tumour and liver spot stretching inside me, and for one millisecond I am suspended in the air.

I wonder what Melila is thinking, watching her Dadda upside-down. And then I fall hard on the ground on to my back.

I lie there for a few seconds and look up at the vaulted sky.

Rain has begun to fall lightly.

I pull myself up and unlock the brakes on Melila’s wheels. The skies open and whip us with torrential rain. I push my daughter homeward and protect my sweet Melila, my zisseleh, by picking up speed.

Am I really running?

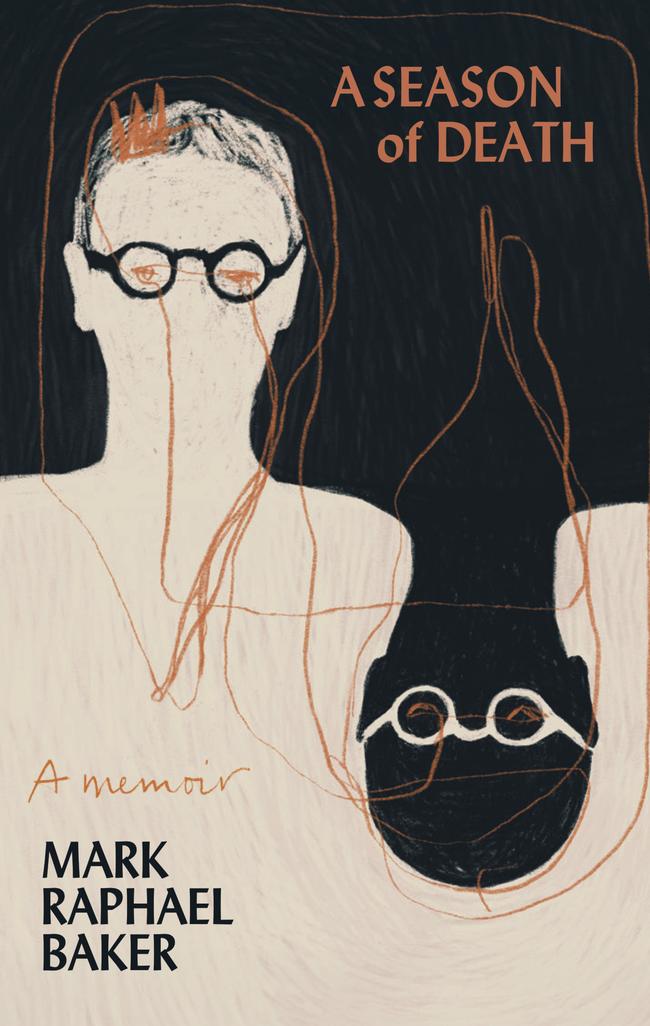

Extracted from A Season of Death by Mark Raphael Baker (MUP), out now. Mark died shortly before the publication of his book.

About the author

Mark Raphael Baker (1959–2023) was the author of two memoirs, The Fiftieth Gate (1997) and Thirty Days (2017). He was associate professor at the Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation in the School of Philosophy, History, International Studies at Monash University. The publication of his last book, A Season of Death (MUP) has tenderly been overseen by his wife, Michelle Lesh, and his father-in-law, Raimond Gaita.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout