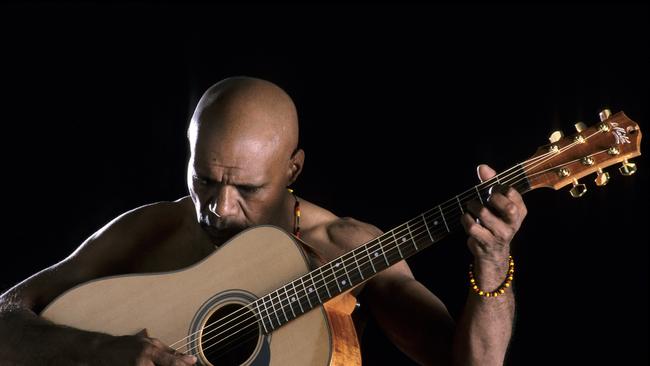

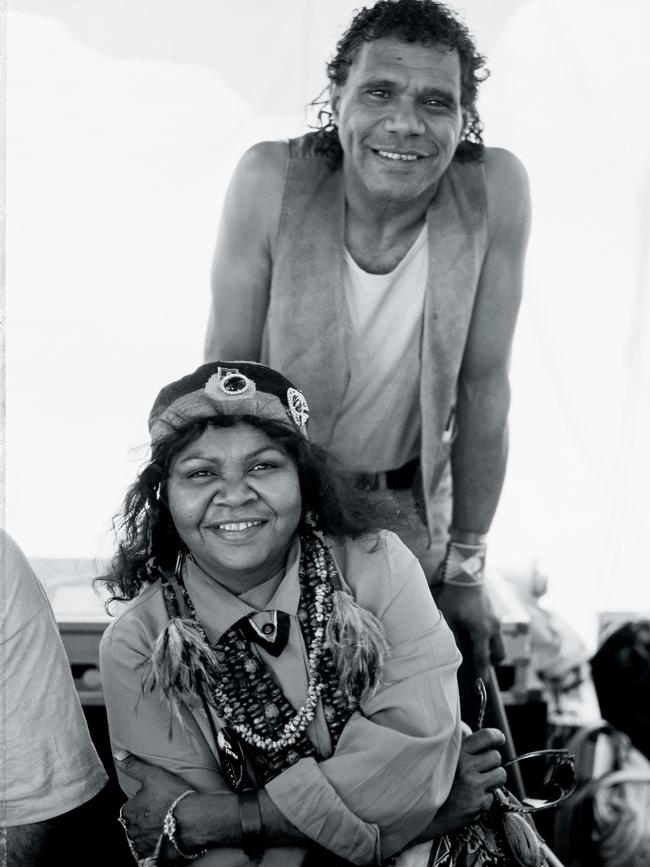

How Indigenous singers Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter overcame stolen generations trauma to forge award-winning careers

Singer-songwriting couple Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter overcame stolen generations trauma to forge trailblazing careers. A new documentary charts their remarkable relationship.

or Archie Roach, the return to his partner Ruby Hunter’s traditional country in South Australia decades ago ended a song-writing “drought”. He recalls that in the months before that trip to the Coorong near the mouth of the Murray River, “everything I wrote was just rubbish”.

Hunter once lived a semi-traditional life in this remote wetland with her grandparents and Roach remembers how, “on the second day, the river gave me a song”. Featuring his slow, aching vibrato, that song, Into the Bloodstream, became the titular track on his 2012 album – his first after his beloved Ruby died suddenly of heart failure, aged just 54, in 2010.

Roach and Hunter share the story of their 38-year relationship and their return to the Coorong in the elegiac, feature-length documentary, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow, which will be released nationally in cinemas this week. That journey may have inspired Roach, but for Hunter, a Ngarrindjeri, Kokatha and Pitjantjatjara woman, it was initially fraught. In an interview with Review, Roach explains that the Coorong is “the place where Ruby was born on country, and the place she was taken from”.

Hunter and her siblings were removed by welfare authorities in 1964, when she was eight. As Roach puts it: “They were told they were supposedly going to the circus for the day, but they never came back to her grandma.”

When Hunter went back to the Coorong as an adult, “all the memories just came flooding back to her” says Roach – about the old, lost way of life and her desolation at her removal, as she and her siblings were split up and sent to different institutions and foster carers. Roach, a Gunditjmara-Bundjalung man who is also a member of the Stolen Generations, recalls: “She just started wailing and I said, ‘Sorry darlin’ I shouldn’t have brought you back here,’ and she said, ‘No’.”

She asked him to take her shoes, “while she walked the country bare foot” just as she had done as a free-spirited little girl. “She did it,” he says. “… It was hard at first and then it became something very poignant.”

After she was removed, Hunter did not see her grandparents again. In a sad symmetry that speaks to the damage wrought by the assimilation era’s zealous removal policies, in 1959 Roach was removed from the Framlingham Aboriginal mission in Victoria, aged three. He never saw his parents again either.

The couple’s extraordinary story – of being cut off from their birth families, meeting at the Salvation Army’s People’s Palace hostel in Adelaide at 16, surviving teenage homelessness and grog addiction and forging stellar careers as singer-songwriters – is told in Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow.

Directed by Philippa Bateman, the film uses a 2004 Melbourne concert starring Hunter, Roach and jazz master Paul Grabowsky’s band, the Australian Art Orchestra, as a narrative spine, teasing out the story of the couple’s long relationship. (They would go on to have two children, Amos and Eban, and to foster three children, Terrence, Krissy and Arthur).

The film is a tribute to the late Hunter, to the couple’s music and to the Coorong itself: As Roach and Hunter perform their soulful ballads and regale the concert audience with anecdotes about their early life and partnership, we are treated to jaw-dropping aerial shots of the Coorong and the Murray. We see multi-coloured cliffs rearing up over the river, pelicans landing on the water like large-bellied 747s, and the area’s vast skies and technicolour sunsets.

Despite the fracturing of her family life, in 1993, Hunter became the first Indigenous Australian woman to record an album, Thoughts Within, with a major record label, Mushroom Records. Roach, 67, agrees she was a trailblazer: “She recorded with what was one of (the) major recording companies back then; no other First Nations woman had done that.”

Wash My Soul makes clear that Hunter played an influential role in nurturing Roach’s career, which saw him inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in 2020, and anointed by Rolling Stone as one of the Top 50 Australian singer-songwriters of all time. Yet in 1991, when he was offered the chance to record his first album, he resisted. It was Ruby who “convinced me to record my first album”, he says.

“I wasn’t going to, but she convinced me otherwise, so yeah, she had a big role in that,” he tells Review. Tiny yet feisty, she put her hands on her hips and told him off, declaring: “It’s not all about you, you know. How many blackfellas you reckon get to record an album?”

After they left foster care as teenagers, both ended up on the streets and battled alcohol addiction, and it was Hunter who was instrumental in Roach’s decision, years later, to kick the habit: “Ruby was the first to say, ‘that’s enough, you’ve had enough’,” he tells Review. “All the drinking, that sort of life’s not good for the two young children we had at the time, two boys. So her doing that, I think eventually I just followed suit and stopped drinking … it was all about the family, I didn’t want to lose my family,” Roach says candidly.

In his award-winning memoir, Tell Me Why, released in 2019, the singer-songwriter gives a searingly honest account of the alcohol addiction he suffered from, before music – and Hunter – helped turn his life around. The addiction began in his teenage years, and despite suffering seizures that put him in hospital and being warned by doctors he was “drinking myself to death”, he could not stop.

He admits that when his second son, Eban, was born prematurely, “I was drinking goom” (a mixture of methylated spirits and water). A suicide attempt, a stint in a psychiatric ward and rehab centre followed.

The memoir, which won the Indie non-fiction book of the year, and Victorian and NSW Premier’s literary awards, explores how his addiction was bound up with his removal from his biological family. As a young adult, long boozing sessions in pubs and parks were a means of bonding with rediscovered relatives he had been separated from years before. While he had a knack of picking up odd jobs, he writes that “work was never a priority, family and drinking went first, and in that period, those two things were inseparable”.

In the film, Hunter remembers a more innocent time, playing games with her sister before they were removed; they would make daisy chains and play knucklebones, thus inspiring her song, Daisy Chains, String Games and Knucklebones, sung in her deep, raspy voice.

She tells concertgoers at Melbourne’s Hamer Hall that during those years at the Coorong, she wasn’t used to wearing clothes. She recalls how others laughed at her when she was taken from the wetland, given western clothes and walked around “with pants on my head”. She comments acerbically on the irony of welfare authorities giving her and her siblings gifts “to ease the pain” of separation from home, when it was the authorities who were causing the pain.

She performs in a red, yellow and black shawl and a headdress of straw and brightly coloured feathers that reminds her of her traditional home, a haven for black swans and other birdlife.

In the film, Hunter says: “Archie is my silent hero and I am his rowdy troublemaker.” I ask Roach, a man of few words, whether she ruled the roost. “She did in the sense that nothing was done without her being consulted,” he says, speaking from his home near Warrnambool, Victoria. If she “wasn’t happy with things” he would soon know about it.

Until he met Hunter, he thought it was just himself and his siblings who had been removed from their biological parents. He was placed with foster parents – the first was abusive, while the second foster family were Scottish immigrants who lived in Melbourne, were loving and championed his interest in music. He can’t remember the removal, although his relatives do “and oddly enough, that is where I get the pain from”.

When he was 14, out of the blue, he received a letter from his sister that turned his world upside down: she told him his biological parents were dead and that his siblings – he hadn’t known of their existence – were alive. Upset, confused and in shock, he soon left his foster home, went in search of relatives in Sydney and Melbourne and ended up living on the streets.

Hunter says during the concert that her foster parents did the best they could but that when she left their home, “things didn’t go right” and she too ended up homeless. Down City Streets is her song about what’s it’s like to be homeless, and features the haunting lyric: “I had no bed I had no home / There was nothing that I owned / used my fingers as a comb”.

Roach became a household name through his song Took The Children Away. In the documentary, he says he first sang it at a gathering of Aboriginal mobs at La Perouse in Sydney on Australia Day, 1988. “I had no idea what I’d done,” he says of creating a ballad that has since become an anthem for the stolen generations.

The filmed concert was performed before the official 2008 apology to the Stolen Generations, and Hunter remarks: “We’re still waiting to be understood.” She also says: “My songs aren’t calling for revolution. They’re calling for recognition and truth.” Is there more understanding about the plight of the Stolen Generations today? Roach replies: “Oh yeah … I think a lot more people understand what took place and what happened to a lot of First Nations people.”

He has fond memories of the 2004 concert – he performed a jazz version of Took the Children Away that “buoyed” him above the song’s undertow of grief – and he and Grabowsky have been frequent collaborators since then. “It was a great time,” he recalls. “It was the first time we got up and performed with Paul Grabowsky and the Art Orchestra.”

Grabowsky produced the album, Tell Me Why, that accompanied his memoir, and Roach says “we’re actually doing stuff again soon. Every now and then Paul gets an idea and if we agree on something, we just go with it.”

Since he lost Hunter, Roach has suffered a stroke and battled lung cancer and now requires an oxygen tube to help him breathe. He says family and friends and agent Jill Shelton have helped him cope with Hunter’s absence: “It was hard at first, coping, but eventually you do.”

Playing music was also a salve, as it has always been for him. He says that through performing, “I have been able to deal with pain in a more positive way”.

Despite his serious health issues, he is about to embark on his final road tour in NSW and Queensland, and has further gigs in South Australia and Western Australia between March and May. When I ask what is driving him, he responds: “It’s what I still love to do; to get up and perform.” He reveals he relies on this for his happiness more than he did when he was younger.

In March, he will also appear at Victoria’s Port Fairy Folk Festival on his mother’s country – the same country he was removed from when he was a toddler. For this reason, it’s always a “special” place to perform, he says, and this year, on a stage that has been named for him, he will share the spotlight with his son, Amos, emerging Indigenous stars including Kutcha Edwards, and community performers.

His Kitchen Table Yarns YouTube series is conducted, as the name suggests, from his kitchen and is also aimed at promoting young Indigenous singers and musicians. He says he and Hunter regarded nurturing young First Nations’ talent as “our cultural responsibility”.

This remarkable man may have been torn from his culture and family at a heartbreakingly tender age, but he is now sharing his hard-won wisdom and musical knowledge with younger generations.

Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow is released nationally in cinemas on March 10.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout