How Indiana Jones made history cool again

Indiana Jones helped make history (and archaeology) exciting. But biodiversity loss is taking place faster than in the five previous mass extinctions, a challenge that might even defeat Indy.

Short of being chosen to play in the Ashes, I am not sure there is a better job in the world than being a historian – especially today. It used to be the case that people thought historians spend all their time lurking in dark corners of libraries, blowing dust off books no one has read, perhaps in a language few people can understand, and then writing a book that was so highbrow and learned that few would – or could – read.

Then along came Indiana Jones, who helped make history (and archaeology) exciting and thrilling to wide audiences. One or two of my colleagues will complain about how Indiana Jones did not follow best practice when it came to handling cultural artefacts and how he insisted on expropriating objects into Western museum collections – sometimes stacked inside a secret warehouse. But most of us are thankful to Harrison Ford for helping to make our discipline feel like an adventure.

Even when confined to those libraries, an adventure is what it is: it is a privilege, of course, to spend one’s time poring over texts and objects of whatever period and trying to come up with new ways to think about those who have gone before us. Yet in today’s world dear Indy would have struggled to contain his excitement at the new frontiers in historical research and the new ways to look into the past.

Many of these avenues have opened thanks to advances in the sciences. Genomic data allows us to understand human migration in past periods of history, producing revolutionary insights that can be accurately measured with hard evidence. For example, haplotypes – sets of genetic variants that can be inherited – reveal linkages between population groups in India, Siberia, Central Europe and Scandinavia. Analysis of the phylogenetic tree of yersinia pestis, the bacterium that carries plague, shows that the disease suddenly diverged into four branches shortly before the outbreak of the Black Death that devastated Europe and the Middle East in the first half of the 14th century – and may in fact have also proved catastrophic in China and West Africa, two regions historians believed had been spared from disaster.

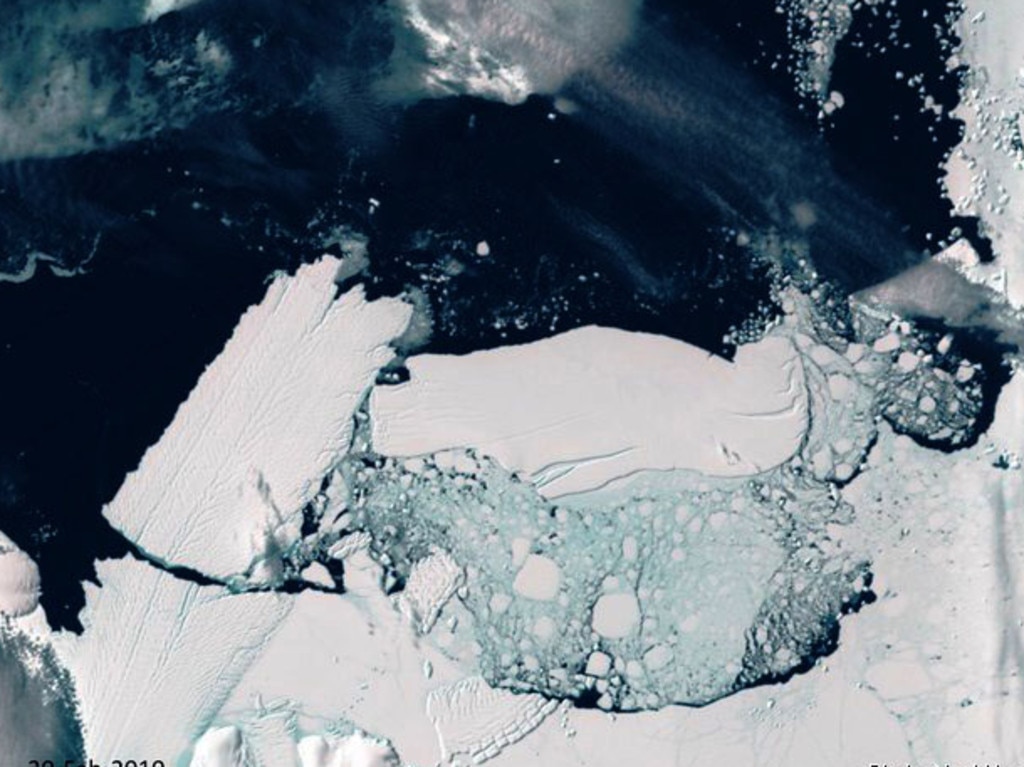

Many of these new materials are drawn from the natural world and allow us to reconstruct past climates and show how the environment has changed. Tree ring data allows us to see where, when and by how much rainfall levels changed over time. Bristlecone pines can show significant temperature changes – something that can sometimes be linked to volcanic eruptions that brought about sharp drops in temperature. Fossilised pollen provides clues as to uses and changes in vegetation, which can in turn give insights into human behaviour — or lack of it. Data from ice-cores in Greenland, glaciers and the Antarctic show air bubbles trapped in the past that reveal changes in carbon dioxide levels, not only since the start of the industrial revolution which marked a shift in fossil fuel emissions but also thousands, tens of thousands and even millions of years ago – including many times when the atmospheric conditions would not have allowed our own species to survive, let alone flourish.

These new tools are extraordinarily important, though not without problems. For one thing, historians must not only specialise in the humanities but also develop scientific and mathematical skills to understand and evaluate the new sources they are looking at. That means revising the antiquated way we think about education, both at secondary school and university level, where subjects are cleaved into silos, with no obvious link between them. For future historians, working on the past will be about integrating biological and plant sciences as much as it will be about reading dusty old texts.

And the results are thrilling. Looking back 40,000 years, we can measure an episode that is known as the Laschamps Excursion, which saw simultaneous shifts of precipitation and wind patterns in the Pacific and Southern Ocean, a sharp decline in the strength of earth’s magnetic field and a spell of unstable solar activity that included multiple massive flares that also affected global weather patterns. The resulting glacial expansions in the Andes and acidification in Australia were so profound they led to the wholesale extinction of large animals.

Or there are the changes to the land mass of what is now Australia at the end of a period called “the Last Glacial Maximum” during which around a quarter of the world’s land area was covered with glaciers, and global sea levels were more than 120m lower than they are today. As conditions warmed, ice melted and ocean levels rose. New research funded by the Australian Research Council using predictive models, satellite imagery, acoustic surveys and topographic and bathymetric LIDAR has revealed multiple human settlements 160km from the current coastline which had to be abandoned as sea levels rose – covering around two million square kilometres of land in the process.

Likewise, we can identify major changes to population sizes as well as changes to lifestyles and lifeways by hunter-gatherers across continental Australia around 1000 years ago that correlate with higher levels of water and food availability – both of which offered humans new opportunities to engage with the natural environment and each other.

We are living through a golden age of historical opportunities that do not require the survival skills and sheer good luck of Indiana Jones to grasp. New evidence allows us to rethink the American Declaration of Independence that was not just about those living in the US wanting to be involved in the political process but was also linked to a series of terrible hurricane seasons that left Spanish and French colonies in the Caribbean severely weakened – and created once in a lifetime opportunities for wealthy elites in Philadelphia and elsewhere whose hands were tied by London’s rivalries with Spain and France.

We can consider fresh ways of understanding the extraordinary rise of a series of empires that blossomed across South and South East Asia in the Middle Ages, a time of benign conditions for trade and food production – conditions which were optimal too for the deliberate and systematic exploration of Polynesia and beyond in exactly the same period.

And we can suggest fresh insights for the ways that societies react to climatic stress that can stem from sudden events – such as volcanic eruptions – or from anomalies or unusually strong differences in the El Nino – Southern Oscillation cycle of alternating warm El Nino and cold La Nina events which is the dominant year-to-year climate signal on earth.

One good example of this comes at the very end of the 1780s, when climatic context is vital to fully understand everything from the rise of the Zulu kingdom to the causes of the French revolution, from the annexation of Crimea by Catherine the Great of Russia to the socio-economic paralysis of Egypt, from the blossoming of British industry to the European settlement of Australia.

Climate shifts, however, are only part of the story. So too are the ways in which our species has engaged with the natural world and reshaped it to suit our own needs. In some cases, this was done brutally and with a sense of triumphalism: “Man Must Conquer Nature” was one slogan coined by Mao to drive forward the industrialisation program of China to transform the country from an agrarian economy into an economic powerhouse. Similar epic processes of transformation of the landscape have taken place elsewhere. Expansion of farming, and of beef and palm oil in particular, has resulted in tens of millions of hectares of forest being cut down around the world in recent decades, with South East Asia alone losing three million hectares a year since the start of this century, while forest fires in 2021 resulted in the equivalent of 10 football pitches being lost per minute.

The way we have consumed energy through burning fossil fuels has not only affected the atmosphere and accelerated global warming but has profoundly affected air quality – and with it health outcomes. Almost the entire population (99.9 per cent) of South East Asia breathe air that is below the guidelines set as safe by the World Health Organisation, which means that life expectancy is 1½ years lower than it would otherwise be. Or there are the by-products of our consumption patterns, with one study published earlier this month estimating there are 170 trillion plastic particles afloat in the world’s oceans – following other studies in recent years that have shown the presence of microplastics in the placentas of pregnant mothers, in the stools of infant children and in all human blood.

And that of course is why perspective is so important: discoveries about the past are thrilling, especially when they come from breakthroughs that are in themselves a set of new superpowers. The flipside is that these tools also serve to sharpen the picture of the world around us – one that is being transformed in front of our eyes.

Biodiversity loss is taking place faster than in the five previous mass extinctions that served to make the planet into the place we call our home. That should provide plenty of food for thought, as well as a challenge that might even defeat Indiana Jones.

Peter Frankopan is Professor of Global History at Oxford University. His new book, The Earth Transformed: An Untold History is published by Bloomsbury. Peter Frankopan will be a guest at Sydney Writers Festival in May

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout