How Holocaust survivors may have killed Nazis on Australian soil

In a new documentary, three Jewish brothers investigate whether their father took revenge for the Holocaust – by murdering a Nazi in Sydney.

Danny Ben-Moshe was just eight years old when he stumbled upon horrific photographs taken by his grandfather during World War II. It was the 1970s, and the London-raised documentary maker recalls: “I was messing around in a cupboard in the back part of our house (in north London) and I found an old, rusty wooden case. I opened it up and it was full of all these black and white photos.

“There were individuals I didn’t know and then there were all these piles of bodies. And I realised they were Holocaust photos. I found out they were taken by my grandfather, who was with the British Army at Bergen-Belsen.’’

The images were captured during the liberation of the German concentration camp and Ben-Moshe’s memory of seeing them for the first time – and at such a tender age – haunted him for decades. “I remember it like it was yesterday,’’ he tells Review, “and I never discussed it with my grandfather. But I constantly thought, ‘Did you ever kill the people who did this to our people? You or the British army?’ It was like, ‘How could we let this happen?’ ’’

Five decades on, Ben-Moshe is based in Melbourne and his latest documentary, Revenge: Our Dad the Nazi Killer?, harks back to his discovery of those Bergen-Belsen photos and the questions about vengeance that they provoked for a Jewish boy whose mother’s family had, tragically, “ended up in a death pit in Lithuania’’.

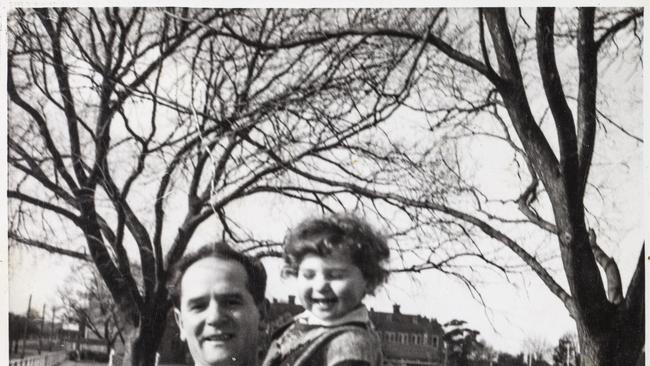

Ben-Moshe’s new film explores a largely untold Australian story of revenge – suspected cases of Jewish vigilantes killing former Nazis who came here, posing as legitimate migrants, after the war. This feature-length documentary is also a family mystery; one in which three Melbourne brothers set out to discover whether their father – Holocaust survivor and former partisan fighter Boris Green – carried out a reprisal murder of a Nazi in Sydney in the late 1950s.

Ben-Moshe stumbled across Boris Green’s remarkable story almost by accident: in 2017, the former Londoner went to a Melbourne barbecue – “I really didn’t want to go to’’ – and met the host, Boris’s son, Jack Green. Jack told Ben-Moshe he was a busy dermatologist and needed a researcher to look into a story about his late father. “He wasn’t pitching it to me as a film at all,’’ the director says. “But it just stood out and resonated.”

When Jack was told by his significantly older brothers Boris may have “taken out” a Nazi fugitive living in NSW, he was stunned. “I was like, what?’’ he says, as he remembered his dad as a mature and mellow personality.

But his brothers, Jon and Sam, remembered Boris differently. In the documentary, they reveal how they heard him talk about a body that had been placed in the Parramatta River. As a highly-trained partisan during World War II, he had fought to “avenge the spilt blood of the innocent” – the estimated two million Jews, including Boris’s siblings, who were murdered by Nazis and their collaborators in central and eastern European shooting pits.

Equal parts detective investigation and historical interrogation, Revenge: Our Dad the Nazi Killer? is written, directed and co-produced by Ben-Moshe and will screen nationally at the Jewish International Film Festival, which opens on Monday.

The documentary will also be released in cinemas in January and broadcast in 2024 by the ABC, BBC, Denmark’s DR and Norway’s NRK networks.

Ben-Moshe is working on a novelised version of this saga of Nazism and vigilante-style justice for HarperCollins Australia, and is hoping to turn it into a podcast.

As they dig into a murky chapter from their father’s past, the Green brothers discover that Nazi networks and covert Jewish vigilante groups were operating in Australia in the decades after World War II. As Sam Green says: “There was a war going on after the war.’’

The brothers engage private investigator and former detective John Garvey, who chases down possible links between Boris Green and the mysterious, premature deaths of former Nazis living in Australia in post-war decades.

One case deemed a suicide involved a man who had apparently died by detonating explosives on his own head. As Garvey puts it: “Interesting way to commit suicide.’’ Fima Green – Boris’s brother, whose wife and child were killed in the Holocaust – was a post-war pacifist, but had been a dynamite expert for the partisans in eastern Europe.

In 1948, before Boris arrived in Australia, Nazi propagandist Arnold von Skerst was found with his head in the oven in his Sydney flat. Twenty years later, an alleged Nazi collaborator who emigrated to Melbourne was also found with his head in a gas oven. In a documented revenge killing, a Ukrainian Nazi collaborator who was persecuting Jews on a ship bound for Australia, was reportedly thrown overboard during a fight with a former Jewish resistance leader.

Garvey says there were “many suspicious deaths’’ of Nazis and Nazi collaborators in Australia in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. These deaths were often ruled as suicides but the evidence suggests they could have been murdered. “I think the sheer numbers warrant some explanation,’’ he says in the documentary.

Revenge: Our Dad the Nazi Killer? is also a denunciation of Australian governments’ failure to bring to justice hundreds – some say thousands – of ex-Nazis and Nazi collaborators, who were mostly from the Baltic states and settled here during the post-war immigration wave. Australia also took in the highest percentage per capita of Holocaust survivors outside Israel, and many of these traumatised survivors arrived at the same time (and on the same ships) as the fascists.

Ben-Moshe, who directed the recent SBS documentary Strictly Jewish, about Australia’s most ultra-Orthodox Jewish sect, describes this nation’s decades-long failure to bring former Nazis to justice as “shocking” and “shameful’’.

“Some of them (Nazis) came without the knowledge of the government, (but) even when it was brought to governments’ attention, they did nothing because they didn’t care and they had their own interests,’’ he says.

Review talks to the writer-director just days before Hamas’s savage attacks on Israeli civilians on October 7, which killed more than 1300 people, and left him feeling “raw and broken’’. “They have shocked me and just about every Australian Jew I know to the core,’’ he said. “The horrific war crimes are hard to comprehend. The human tragedy, old people and young kids kidnapped and paraded ISIS-style in Gaza, is heartbreaking.’’ Israel has sinced launched massive air strikes on Gaza, which have been backed by the US but condemned by Arab nations. This week, each side in the conflict blamed the other for a Gaza hospital blast that reportedly killed hundreds of people.

Ben-Moshe found it “sickening, almost worse than the war crimes themselves” that Sydney protesters defended Hamas’s October 7 attacks and used the atrocities to “espouse their Jew hatred’’. He reflects: “If I and just about every Australian Jew I know are dismayed and disgusted … at the support in Sydney for Hamas’s ISIS-like war crimes, how must Boris have been justifiably seething (over the Nazis who escaped justice after moving to Australia).’’

So who was Boris Green, watchmaker, proud father – and possible assassin? A respected member of Melbourne’s Jewish community, he was born in Belarus and died in 2008, aged 95. He fought Nazis in eastern Europe as part of the Russian partisan movement during World War II and was credited with saving many Jewish lives. He suffered a degree of profound grief most of us will never know: he lost seven siblings to the Holocaust; of nine children, only he and Fima survived.

Boris emigrated to Australia in 1949, joining Fima, who was already here. After marrying Chana, he opened a jewellery shop in Richmond and had three sons: Jack, the youngest, is a medical specialist; eldest son Jon is a rabbi, while Sam pursued a career in music. After the war, Boris gave testimony about Nazi war crimes he had witnessed in eastern Europe to international commissions and later spoke at a Holocaust commemoration in Melbourne.

The documentary explores the morality of post-war revenge killings in the context of Nazis getting away with their crimes, and the catastrophic losses suffered by Jews whose families were wiped out in the Holocaust.

Says Ben-Moshe: “We have to understand, we’re talking three to eight years after the war. That’s like yesterday. “There are cases I have of someone getting on a bus and seeing an SS that killed their family. … In the (Australian) migrant hostels, I’ve got reports of survivors lying under their sheets at night, while their fellow inmates are talking jovially about the Jews they killed in the war. What would you do? That’s what the question is, what would you do if you knew mass murderers of your family? But more than that, what would you do if you saw that person, went to the government, went to the police and you realised they were doing nothing about it?’’

This story resonates powerfully with the filmmaker because “my own family have a Holocaust backstory’’. He says Boris moved between closely-connected Jewish communities in Belarus and Lithuania. “It was like, ‘Oh! Maybe he fought the killers of my family’,’’ he says.

Review asks Ben-Moshe whether he identifies with Holocaust survivors who approved of reprisal murders of Nazis and their collaborators. His answer is emphatic: “Yeah, I’m on Boris’s side. I think the outrage is not with what Boris may or may not have done, but with the government establishment, who at best turned a blind eye and actually recruited and protected Nazis.’’

In the film, former investigative journalist Mark Aarons says that during the Cold War, Australia was asked by Britain and the US to take “our share” of ex-Nazis or Nazi collaborators who had fought against Soviet communists, seeing them as potential intelligence assets. Some were recruited by ASIO.

The Hawke government finally set up the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) in 1987 to probe Nazi war crimes allegations made against Australian citizens and residents. The unit conducted 841 investigations and identified 27 cases of suspected war crimes. Ultimately, it referred only four cases to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, and due to issues including the passing of time and death of witnesses, no convictions were secured.

In 2013, the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, which hunts Nazi war criminals, sharply criticised Australia for failing to do enough to bring perpetrators of the Holocaust to justice. This followed a High Court decision to reject Hungary’s request to extradite accused war criminal Charles Zentai on the grounds the offence of war crimes did not exist in 1944. (In 2015, Serbian-Australian Dragan Vasiljkovic became the first war criminal to be extradited from Australia to face trial. He was jailed in Croatia over crimes he committed during the Balkans war and was released in 2020.)

Ben-Moshe had been a “bored law student” at the University of London before he completed a Jewish studies PhD at Melbourne University, married Australian laughter therapist and author Ros, and turned to filmmaking. He is working on a virtual-reality film about the huge democracy protests that swept through Israel and pre-dated the Hamas attack.

For the documentary, the Green brothers returned to Vilnius in Lithuania where their cousins, aunts and uncles lived before the Holocaust. They also visited the nearby Ponar shooting pit where these same relatives were murdered “because of crazy hatred’’.

Jon says he feels “really torn’’ by the investigation into his father, a private man who rebuilt his life from a ruin. But Jack wants to keep digging. Ben-Moshe says “there were a couple of times when things exploded, things got a bit heated on set because of the emotion of what we were dealing with’’. He says viewers “will draw their own conclusions’’ about Boris Green’s guilt or innocence and whether his alleged actions were justified.

For the director, the most disturbing part of this story is the official indifference to the Jewish people’s plight and demands for justice, before and after World War II. “As a society, we can be obsessed and shocked by the horrors of the Holocaust – Auschwitz, chimneys, gas chambers, but actually what I find almost more staggering, is what happened before the Holocaust that allowed it to happen, with the allied countries not providing Jews with a refuge,” he says. “And then, the insult to injury after the war by not pursuing justice.’’

Jon Green regards as “heroic” the family life his father Boris built in Australia after he lost his home, community and closest family members during the Holocaust. Though Boris lived into his 90s, his son says that in light of the possible revenge killing, “I’m still trying to understand who he was’’.

Revenge: Our Dad the Nazi Killer?is screening at the Jewish International Film Festival. The festival runs nationally from October 23 until December 6.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout