How Geelong’s Back to Back Theatre became the toast of Venice Biennale

Of all the theatre companies in all the world, a small, independent regional troupe of disabled and neurodivergent actors from Geelong was chosen by the Venice Biennale as the recipient for the prestigious Golden Lion.

The Golden Lion is on the loose. That gilded apex of international cultural achievement, which just minutes earlier had been held triumphantly aloft by members of Geelong’s Back to Back Theatre company, now is nowhere to be seen. A large red velvet box that housed the Venice Biennale lifetime achievement trophy sits empty on the stage at the Biennale’s historic headquarters, Ca’ Giustinian, as cultural and consulate attaches from Italy and Australia mingle and chat with the Australian theatre troupe.

The event’s emcee, Manuela Caldirola, looks concerned. She seems to be asking around. Anyone seen a lion? Yay high. Gold? The Leone d’oro does have wings. Surely it hasn’t flown the coop? It’s an unlikely proposition with this amount of military brass in attendance; Italian navy and army generals, all pressed fabric and gleaming buttons, are observing proceedings in the ballroom of this 15th-century gothic former palace overlooking Venice’s San Marco basin.

Back to Back actor Tamika Simpson is sitting quietly two rows back. She has a secret. Not the big one: that it’s her 40th birthday in a few days. She let that cat out of the bag earlier. There’s another cat in her bag. Its golden wings are poking ever so slightly out the top of a semi-zipped tote. Simpson cradles the precious cargo. Caldirola twigs, and inquires politely if the Biennale might – briefly – return the Leone d’oro to the stage for the artists’ talk. Simpson negotiates. She’ll take it out of the bag but it stays on her lap. The Golden Lion is in safe hands. And it is going nowhere. Nowhere but home, to Australia.

A pair of multimillion superyachts are docked conspicuously outside Arsenale di Venezia, the city’s former fortified naval armoury and shipyard on the famous Riva degli Schiavoni boulevard. Young women in bikinis are taking selfies on board as thousands of tourists, sweltering in the heat below, swarm across the city’s bridges and up into its rabbit warren of historic canals.

It is, as weekdays in the Italian city go, a pretty standard affair. But inside the walls of the Arsenale – since 1980 the home of the Biennale Teatro, the cultural jamboree’s international theatre program – there is a crisis unfolding. Australia’s Back to Back Theatre, the independent regional Victorian theatre group whose cast is drawn from the disabled and neurodivergent community, is due to perform after having been personally invited by Biennale Teatro program artistic directors Stefano Ricci and Gianni Forte.

Its two-show run of Food Court, the company’s 2008 hit, is a sellout. The cast and crew of more than 20 all have made it safely to the canal city.

Its sets, however, have not. In fact, the stage designs for its production have been seized by Italian customs officials. “It’s a bit of a nightmare,” artistic director Bruce Gladwin says. “The set didn’t arrive and has been held up in customs in Milan.” The problem is a freighting weight issue.

The show’s design – a large luminous inflatable that fills the stage with an opaque plastic front – gives the show a “dreamlike quality”, Gladwin says.

It is in many ways an essential juxtaposition to the production’s dark central theme: bullying and its consequences.

“Without our sets, we will be using light and a lot of darkness in the show,” Gladwin says. “Food Court is in many ways a brutal show. Having no sets makes it even more brutal.”

The production, inspired in part by a schoolyard bullying event in the early 2000s that was filmed and went viral, was conceived and written by cast members Rita Halbarec, Nicki Holland, Sarah Mainwaring, Scott Price, Mark Deans and Gladwin.

The show features The Necks, the cult Australian improvisational jazz band comprising Chris Abrahams, Tony Buck and Lloyd Swanton. (“I was always a fan of their music. I just cold-called them, and they had seen our work and said yes,” Gladwin says). The trio’s ever-changing score runs the full length of the 90-minute show.

The story takes place “between the Asian Hut and The Juice Bar” and details the personal humiliation and abuse of one person at the hands of two others.

Mainwaring, who has cerebral palsy, plays the protagonist. She is worn down emotionally and then physically by characters played in Venice by actors Simpson and Sarah Goninon, to the point of being forced to strip naked. Mainwaring is ordered to perform a slow, tortuous dance – a ballerina without a music box – as she is beaten down, figuratively and literally.

“It’s so ballsy,” Price says of Mainwaring’s performance.

Gladwin says the actor is emblematic of the company’s deep well of talent. Before joining Back to Back in 2005, Mainwaring had done many years working with La Mama in Melbourne. She says she relishes performing. “I am never nervous (taking my clothes off),” says Mainwaring, whose condition causes her to speak slowly. “In that moment I am playing with the kind of experimental theatre I had done at La Mama with theatremaker Lloyd (Jones). I am always prepared to just go for it.”

Simon Laherty has been with the ensemble for 21 years. His face – albeit then adorned with a Hitler moustache – is well known to Australian theatregoers from the company’s global hit Ganesh versus The Third Reich. “I love being an actor,” he says, “because I love improvisation in the making of the work in the rehearsal room. I love doing research and going out there and getting it done.”

Price, who runs his own successful TikTok and YouTube channels, says being a role model for other neurodivergent people is an agreeable side benefit to his work on stage but it’s not his primary concern.

“I love to act,” says Price, who has autism. “(It’s important) to be modest about my achievements. At the end of the day, I’m there to do my job and do it well.” Gladwin says the company’s great strength lies in the universality of its themes. “I feel like, for instance in Food Court, we made something that is not so much about these characters on stage and that power battle, but that it is a kind of internal battle within all of us. These characters represent some sort of internal voice that we all have at times.”

The genesis of any Back to Back show always comes from the cast, Gladwin says – the company aims for inclusivity above all. Performer is dramaturg is playwright.

“Much of what we perform is about lived experience,” Gladwin says. “For each of the actors we ensure there is something of a curated objective for them, which is often about extending them as performers.”

Mainwaring agrees: “In the rehearsal room, when we find territory that may be difficult, it can be interesting to explore it. (Those discussions) often lead to bigger things.”

Later Gladwin will receive a call from customs. The issue has been resolved. The sets can be delivered that afternoon. But it’s too late. “We just push ahead with plan B. That’s what we do,” he says.

Universal recognition

Perhaps more than any other Australian theatre company, Back to Back Theatre is used to dealing with challenges. Indeed, as one of the world’s leading arts groups that employs and engages with the disabled and neurodivergent community, it’s practically a part of the company’s modus operandi.

Founded in 1987, Back to Back began against the backdrop of mass deinstitutionalisation for people with disabilities in Australia. It had been intended as a practical way for members of the disabled community to move into wider society, but after its debut production Big Bag hit the stage in 1988 it quickly made a name for itself as a company of real substance and quality.

Food Court was a hit in 2008, but the company shot to global prominence in 2011 with its multi-award winning show Ganesh versus The Third Reich, a piece about the Hindu deity seeking to reclaim the swastika from the Nazis. It was universally acclaimed, and praised in The New York Times as “a vital sense-sharpening tonic for theatregoers who feel they’ve seen it all”.

Since that point, the company has been on a serious upward trajectory of recognition. It has won numerous Green Room awards domestically. In 2014 the troupe claimed the Edinburgh International Arts Festival’s Herald Angel critics award, before in 2022 taking out the prestigious and lucrative $370,000 Ibsen award in Norway.

Back to Back is now a tour de force. The company’s performers spend up to 20 weeks a year on the road, says Gladwin. The troupe is made up of a core group of actors: Laherty, Mainwaring and Price. Deans, a stalwart of the company, retired last year. But Gladwin says the grassroots connections are of utmost importance. The company works closely with high schools and community groups, casting for auditions from its pathways programs at schools and workshops and residencies around regional Victoria.

Back to Back also is a registered National Disability Insurance Scheme provider, which helps keep its actors in full-time paid work. Says Tim Stitz, Back to Back executive producer and co-chief executive: “We have always paid our performers as we’ve paid any performer – above the Live Performance Australia award rate or higher. And in some ways that’s the biggest impact we can demonstrate – that we treat everyone the same.”

He says the NDIS is not a funder in the traditional sense – the company is supported by Creative Australia, among other entities – but its staff work with the plans of individual members to help further their careers.

“A couple of our members (outside the company) have employment as a goal and that means in the rehearsal room every week we can support each of our performers, particularly artists with disabilities, to reach a level playing field at work.

“The other thing that is great about how we engage with the NDIS – and it’s certainly still got a long way to go – is that the government is talking about art as real work in the disability space.

“(There has always been a perception) the arts is a hobby or a something you can do as therapy, where we see it as professional practice.”

Earlier this year federal Arts Minister Tony Burke addressed parliament to sing the group’s praises: “They are one of our most successful exports. Back to Back draws into question some assumptions people often would have about what’s possible in the theatre. Disability access in the arts doesn’t simply mean access to seats in the audience. It also means access to the stage.”

Olympics of art

The Venice Biennale started in 1895, when the first international art exhibition was staged in the canal city. The event expanded in the 1930s, including more countries and saw the launch of new sub-festivals in the areas of music, theatre and cinema. (The 1932 Venice film festival was the first of its kind in the world.) The Biennale branched out to architecture in 1980 and in 1999 dance was included.

Australia’s involvement at the Biennale officially began in 1954 in the Giardini, the sprawling park at Venice’s eastern edge that houses 30 permanent pavilions; others are dotted around the city. Sidney Nolan, William Dobell and Russell Drysdale were that year’s participants. But Australians had represented Britain in the decades preceding the famous triumvirate’s debut on the world stage. Between 1897 and 1936, 10 Australian artists exhibited for Britain at Venice, including George Lambert, Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton.

Australia’s pavilion building in the Giardini – a design by Denton Corker Marshall in black granite – was completed in 2015, replacing Philip Cox’s non-permanent structure that had existed since 1987.

The Biennale is often referred to as the Olympics of art. But it’s not a tag universally appreciated, or even understood. As writer and curator Juliana Engberg states in her foreword to Kerry Gardner’s 2021 Australia at the Venice Biennale: “Every time I hear the worn-thin description of the Venice Biennale as the ‘Olympics of the art world’ it makes me want to run full tilt into a brick pavilion … I only ever hear it in Australia, where sport reigns above all else. It’s not a race, nor a competition. It’s a participation.”

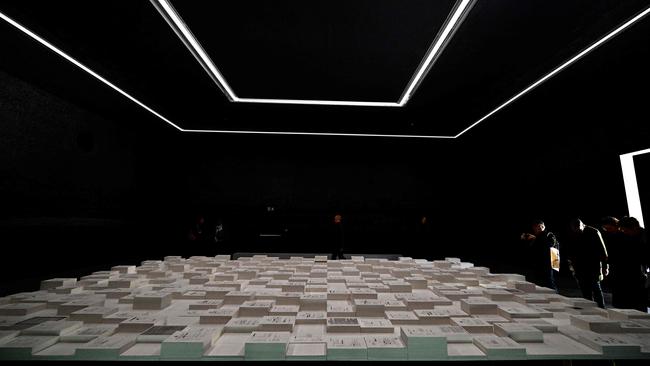

Forty-one Australians have represented Australia at the visual arts component of the Biennale during its history. We had not come close to an award, let alone the top gong. Archie Moore would change that. In May, the Queensland Indigenous artist was announced as the winner of the Golden Lion for best national participation at the Biennale for his large-scale installation kith and kin. The Kamilaroi-Bigambul artist’s painstakingly hand-drawn chalk-on-blackboard family tree traces a 65,000-year genealogy – its more recent branches are truncated and in some cases eradicated altogether. The 60m-long square wall surrounds a black ink well, in the middle of which are perched stacks of paper on a large square table. The sheets are coroners’ reports documenting Indigenous Australian deaths in custody. It is the standout exhibition of the 86 countries whose work is on display. (On the day Review visited the Giardini, Moore’s pavilion was by far the most visited of all pavilions).

It also was announced Australian filmmaker Peter Weir would be celebrated with a Golden Lion. The Australian, best known for Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Gallipoli (1981), Dead Poets Society (1989) and The Truman Show (1998) will received his award in August from Biennale film festival director Alberto Barbera.

Then there was a phone call from Venice to Geelong. The reason? Of all the theatre companies in all the world, a small independent troupe from regional Victoria would be honoured with the prestigious Golden Lion for lifetime achievement.

The Biennale had two questions for Gladwin and his team: would they accept the award? And might they consider performing on one of the globe’s most important stages alongside some of the world’s most celebrated theatre practitioners? The answer was simple: si.

An audience transfixed

There is a line snaking around the block to the entrance of Teatro Piccolo, one of the largest auditoriums at the Biennale Arsenale precinct. The former fortress’s high, reinforced brick walls are a startling juxtaposition to the merriment emanating from the nearby packed trattorias selling pasta and espresso. It’s 10pm and audiences have emerged from shows from the world’s best theatremakers. Sleeping Beauty, by Teatro playwriting under 40 winner Carolina Balucani and directed by Fabrizio Arcuri, is a sellout. Briton Tim Crouch’s one-man show Truth’s a Dog Must to Kennel, a kind of King Lear meets open-mic stand-up show, and award-winning Italian playwright Rosalinda Conti’s Cosi Erano le Cose Appena Nata La Luce – a theatre rehearsal room read-through charting the end of the world – both have met with critical acclaim. Tomorrow night, enfant terrible and international theatremaker du jour Milo Rau will stage his confronting and moving Medea’s Children.

The show charts a real case of mass infanticide at the hands of a Belgian mother and contrasts it with the titular Greek myth. It is a most confronting, haunting and remarkable work. As the doors to the Piccolo open and we take our seats, The Necks begin to play. Laherty emerges from behind the curtain with a boom mic. And Back to Back does its thing.

No one notices the sets. The audience is transfixed.

After the curtain call, many remain in their seats. Some are crying. One theatregoer, tears in her eyes, utters: “Holy shit. I’ve never seen anything that powerful in all my life.”

“Our fears, our puritan tolerance, our moral blindness are blown away by Back to Back Theatre’s tales of dangerous worlds, where diversity carries with it the amplification of knowledge, of inclusion. This is theatre deserving (of the Golden Lion).” Biennale Teatro artistic directors Ricci and Forte are addressing the assembled at the Ca’ Giustinian as Biennale president Pietrangelo Buttafuoco prepares to hand over the trophy. “The troupe has challenged perceptions of societal normalcy.”

Price couldn’t agree more. “I’m always challenging ableist perceptions,” he says.

“Things like Back to Back do have power. Real power. And I think things are changing in society. Slowly.”

Change is coming for the company, too, says Gladwin.

“I think the expectations now of an able-bodied, non-disabled director working with a group of disabled artists is slightly out of date,” he says. “I think I’m working towards my own redundancy. If we are doing the job well, my job is irrelevant. I am irrelevant.”

Soon after, at a swanky post-ceremony cocktail event on the rooftop terrace, Simpson blows out the candles on a birthday cake. The lion sits boxed under an umbrella. The company sings Happy Birthday and poses for photographs.

Gladwin smiles. He says the company is excited and humbled by the award.

“It is a great acknowledgment of the actors’ commitment and professionalism over decades of touring,” he says. “They really do work tremendously hard. We are very grateful.”

Having won the world’s highest theatre honours – the Ibsen, Edinburgh and now Venice – what possibly could be next?

“The sky’s the limit,” Price says with a smile.

It’s also the next destination. Turns out the Golden Lion can fly after all. Economy class. From Venice via Dubai to Melbourne, and out to its new home in Geelong. Stitz posts a photo on the company’s WhatsApp chat group of the precious cargo, ensconced in its velvet box. “The Lion is safely packed under my feet!”

Before he leaves the floating city, Price reflects on this trip. What does it all mean: the award, the work, the company, the future?

“I think this experience will change some things, some perspectives,” he says. “I really do.

“I hope you’re proud, Australia. We’re coming back home. We’re coming home with the Golden Lion.”

Tim Douglas travelled to Italy as a guest of the Venice Biennale.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout