How beaches framed one immigrants journey to belonging

A new book charts the journey of a young immigrant, struggling to be part of the crowd on Cronulla Beach, to a confident woman holding her own in the waters off Manly.

In Cronulla, the beach is a white crescent that seems to curve on forever. Off Shark Island, famous for its hollow rides, surfers wait for that perfect wave.

It is a hot summer’s day in December 1988: a perfect hard blue sky, a perfect blue swell, a light breeze carrying the tang of salt, sunscreen and baby oil, with the slight undertone of sewage and the acrid scent of orange slices we’re sucking noisily from a Tupperware container.

I’m 15, out with a group of mates — freckly, lanky-limbed Shire girls with blonde fuzz on their thin arms, five paper dolls in a chain. Orang putih, we called them in Malaysia: white man. Or gweilo — white ghosts. I’m the odd one out, a brown Malaysian-Indian among lobster-red-and-white Cronulla locals. As they slather on Johnson’s Baby Oil in pursuit of the perfect tan, I uneasily watch my skin tiptoe towards a shade of burnt roti. The tube of Fair & Lovely cream in my bedroom floats by accusingly in my mind. Never mind. I’m out with my mates. I’ll pay for my tanning crimes later.

I dig my toes into the sand, marvelling. I’ve made it. In Sydney’s southern suburbs, the beach is where everything happens, and on this stretch of Elysian coastline studded with stunning beaches — Wattamolla, Jibbon Beach, Garie, Burning Palms – Cronulla Beach (or kurranulla, in the local Aboriginal language, meaning “place of pink shells”) is king.

Here, 26km from the Sydney CBD, the good people of the Sutherland Shire come to play. Hedonism rules.

It’s been a tough year. In January, my family arrived from Malaysia to start a new life in Sydney, which was in the full swing of Australia’s bicentenary celebrations. The Sutherland Shire is our new home. The birthplace of Australia, Captain Cook’s landing spot — to locals it is God’s Own Country. Bordered by the Georges River to the north and the Royal National Park to the south, its watery geography of rivers, bays and ocean keeps the rest of the world at arm’s length.

It’s a funny place, the Shire — smugly pretty, insular, the self-anointed custodian of the Australian dream.

My surgeon father — cantankerous, brilliant, awarded a medal by the Sultan of Selangor for his work in repairing diseased spleens, cancerous livers and, on one memorable occasion, extricating a steering wheel from the chest of an unfortunate truck driver — gets a job as a locum GP in a medical practice, where the odd racist bogan refuses to see the “Indian bloke”. My mum, a GP back in Malaysia, juggles four children and the house, studies for her medical exams, plants a spindly curry leaf sapling for her famous curries, and clings valiantly to her Catholic faith. My older sister and I get packed off to a large Catholic high school in Sutherland. “Abos”, someone calls from a passing ute. My kid sister gets called a “chocolate frog” at her primary school.

Sylvania Waters, where we settle, is an odd little slice of suburbia. Developed by L.J. Hooker in the 1960s and designed with the Florida Keys in mind, the suburb floats on a series of man-made canals on land reclaimed from the mangroves of Gwawley Bay.

The cashed-up, aspiring tradies drawn here in the 1960s — Prime Minister John Howard’s future battlers — are being slowly jostled out by professionals like my family. White faces dominate, but there are at least two other brown immigrant families like ours — both from Sri Lanka. Conservative values prevail across the Shire; Howard will describe it later as “a part of Sydney which has always represented to me what middle Australia is all about”. It’s unearthly quiet. Back in my hometown of Klang, outside Kuala Lumpur, my life had a distinct soundtrack. I woke up every morning to the call of the muezzin from the nearby mosque; amahs arriving for work on rickety bikes; the nasi lemak lady setting up her roadside stall; the honk of our driver Uncle Peter’s taxi arriving to take us to school; the elderly teacher who came every Saturday to teach us the beautiful, spidery calligraphy of Arabic. Even the wildlife was noisy — huge black crows gathered to perform a mournful dirge all day long.

Here, it’s deadsville. The silence is broken only by the sound of the Mr Whippy van — until one memorable day in 1992, when our quiet slice of suburbia explodes. Australia’s first reality TV program, Sylvania Waters, starts filming here. Suddenly, there are cameras and TV vans, and paparazzi stalking the Donaher family down at No.48 Macintyre Crescent. It is a social and cultural moment — the birth of modern reality TV in Australia. One of the family’s sons catches the bus with my younger sisters; we imagine ourselves, wistfully, as celebrities by association.

I navigate the sprawling yellow-brick buildings with daily dread.

My sister and I, sartorial trendsetters back home, are branded instant rejects when, still waiting for out-of-stock uniforms, we turn up every day in the height of Kuala Lumpur late ’80s pasar malam fashion: think flowing palazzo pants and asymmetric tops printed with misspelled designer labels.

This is the era of Kylie and bubble skirts and bleached, crimped ponytails. “Bush pigs”, a boy in my sister’s year hisses as we walk by. I don’t know what it means but flush with shame nevertheless. We’re the wrong colour. The Shire circa 1988 is almost total vanilla apart from a small handful of POC: at school, there is Lydia, a swarthy Egyptian; Leanne, of Chinese ancestry; and us. Oh, and two super-hot Melissas, one Vietnamese and one Filipino, who have nimbly jumped the colour bar and miraculously ascended the social ladder into the popular girls’ group. I study them, fascinated, envious: Country Road bags, scrunchies, casual sense of belonging.

During recess, I watch the other kids line up at the tuckshop, buying greasy Chiko rolls and meat pies while I try to hide my leftover sambhar and rice and inji pickles. I want to be in the canteen queue, my pockets heavy with coins. I practise sounding Aussie. I want to erase the singsong lilt, the peaks and troughs of Malaysian English. I envy the careless, fast stream of others’ speech, punctuated with “yeah-nahs” and fluent swears — I want that bone-dry, flat, sixth-generation Aussie drawl. At home, I turn words over and over on my tongue. Howyagoinorright?

One day, our history teacher brings up the hanging deaths of Aussie heroin traffickers Kevin Barlow and Brian Chambers in Malaysia just two years before. The executions had gone ahead despite the Australian government’s pleas for clemency, and public outrage is still simmering. “Savages,” someone hisses in class, giving me the side eye.

I crave a tribe, a new skin, a sense of belonging, an identity. Finally, I make a friend. She is skinny, freckled, kind. My first Australian mate. One afternoon, we sneak off on the train to the city. I buy a much-coveted Country Road bag. We buy a bottle of white wine with her fake ID and drink it until we puke in a gutter in an alleyway near Martin Place.

We dare each other to shoplift from the glossy shops of Castlereagh Street filled with Rolex watches and Chanel handbags; stagger down the city streets.

Head spinning, I catch my breath at seeing the Harbour Bridge up close, its massive lacy iron back arcing over two points of land; and the seashell silhouette of the Opera House appearing and dissolving like a houri in the summer heat, a million mosaic tiles catching and reflecting the sun and the water, stretching blue, bluer, bluest into infinity. It’s a good day.

And then one weekend, I find it, a new home — Cronulla Beach.

So here I am, on this hot December day, nearly 16. I’ve shucked off my Malaysian-Indian skin and I’ve got baby oil on my legs like a real Shire chick. I’ve made friends, I’ve learned how to tie my hair in a scrunchie, I’ve almost mastered “the claw” fringe. I speak with a drawl and upward inflections, I listen to The Angels and Icehouse, I have snuck out twice on a fake ID to notorious Shire nightclub Carmens and Northies, gotten drunk on cheap white wine, had a ciggie or two. I’ve done the miraculous: jumped the colour bar, like the brown Melissas. I’ve arrived.

And then I hear it. A gaggle of surfers walk past. “F..k off back to Brighton, will ya?” A honk of ugly laughter, and they’re gone.

Live long enough in Sutherland Shire and you soon become familiar with its unwritten codes and rules. If you’re a white local, Cronulla is your beach. If you’re not, you go to Brighton-Le-Sands. Geographically, the two beaches are neighbours — about 15km apart. Racially and culturally, however, they may as well be on different planets.

Bordered by the City of Canterbury Bankstown, Brighton-Le-Sands sits on the calm blue shores of Botany Bay. Dubbed “Little Greece by the Bay”, it’s a magnet for all kinds of wogs: Macedonians, Italians, Croatians, Arabs — you name it. They flock here every Friday night in their Serie A or Premier League soccer shirts, driving hotted-up purple Toranas.

This is where Puberty Blues’ shunned Westies have long come to congregate, flirt, eat souvlaki and dolmades by the water, and drag race their cars along The Grand Parade, rubbing shoulders with Arabic-speaking families from Bankstown — women in hijab licking ice-creams, bearded men in skullcaps — and everyone gawking at the beachfront McMansions guarded by fat stone cherubs and an Italianate fountain or two: the other migrant Australian dream writ large, paralleling the picket fences, chlorine pools and Hills hoists of the white Aussie equivalent.

I’ve long stopped going to Cronulla. Here, I float in the shark-netted enclosure where the old baths built by enterprising tramway pioneer Thomas Saywell once drew holiday crowds, before being demolished by a freak storm in 1966. I stare up at the blue sky. Musical Arabic floats from a group of women in hijab on the shore. I watch planes take off at Sydney Airport. I spot the distinctive Kelantan kite logo of a Malaysia Airlines plane, and wish that I was going home.

Time telescopes. I am brown, surrounded by brown beachgoers. This is my beach now, my tribe, my Australia.

***

The day starts like so many other days in summer. It’s a beautiful blue-sky morning. The sea is green and glassy.

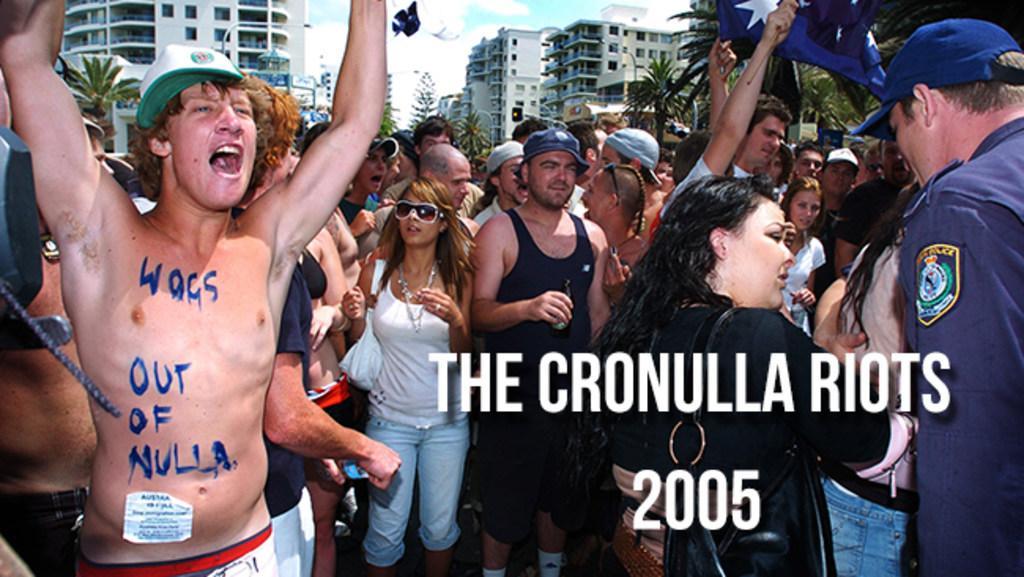

After a text message starts circulating — “This Sunday every F..king Aussie in the Shire get down to North Cronulla to help support Leb and Wog bashing day” — white youths, many with the Southern Cross inked into their skin, take to the beach with T-shirts bearing slogans such as “Wog-free Zone” and “Ethnic Cleansing Unit”. They come, they say, to reclaim the beach from the intruders — the young men of Middle Eastern appearance who catch the train from the southwest to Cronulla.

Tensions have been boiling for weeks. Accused of harassing young white Aussie women, these young men now come under attack. Drunk white mobs draped in the Australian flag sing the national anthem and chant racist slogans. Police and paramedics try to provide shelter but also come under attack. Ugly, violent images are beamed around the world. For weeks after, Cronulla is awash with police.

I moved out of the area years earlier, but as an ex-local and journalist for a national newspaper, I am asked to investigate the fallout.

To me, the riots were inevitable.

A different Australia had slowly emerged in the preceding years. These young white men had come of age during the decade of Howard’s conservative administration — they had witnessed the Tampa affair, the boat people scaremongering and the tacit acceptance of Pauline Hanson and her divisive politics, and had been moulded by the panicky xenophobia that swept the nation in response not only to the arrival of asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere but also to the growing visibility and affluence of Australia’s non-white communities. The Australian flag had become embedded with a silent message for non-white Australians: “You’re out, and we’re in.”

Along the way, Indians like my family have been increasingly caught up in the conflation of brown skin with terror, fuelled by September 11 and the 2002 Bali bombings. Go home, Mussie. Savages.

It feels strange to be back here, with a notepad and tape recorder. The beach is as beautiful as ever, the waves rolling in from Shark Island as gnarly as ever. But the surfers are missing from the water.

It is a hot January weekend and I’m on another beach, far from the shores of my teenage years. In search of a sea change, my husband and I and our twin teenagers moved a year ago to Manly, on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. I sit on the sand watching the families gathered on the skinny slice of beach on the wharf end, where the green-and-yellow ferries from Circular Quay come in.

Like the Shire, Manly plays host to very different beach cultures. On the main beachfront, from Queenscliff to South Steyne, white faces dominate: setting up blue-and-white beach shelters and picnic blankets, their children in neon-pink Nippers rashies, their teenagers taking surf lessons and hanging out with their mates. On the harbour side, 300m away, a different beach culture thrives: multicultural, filled with large, multi-generational families drawn to the calmer waters of Manly Cove.

I watch the crowd. A family of Sikhs, the men in bright turbans, the women in shiny salwar kameez pushing prams, try to find the now defunct aquarium. There are two young men who look Middle Eastern snorkelling past a young Irish woman made buoyant by an enormous, sunburnt, pregnant tummy. A bearded young patriarch, Lebanese perhaps, in blue-and-whitestriped trunks, teaches his young son to swim. His wife is in hijab, marshalling her little clan in high-pitched Arabic. Their daughter, maybe 12, pudgy in a floral rashie, methodically fills a bucket with sand.

I swim out to the shark nets, bumping into an older white Aussie swimmer who gives me an irritated glare; no ethnics dare come up to the nets, but I’m a local now and I wave him off. No one can make me feel like an outsider again. I float on my back, listening to the foghorn bleat of the Manly ferries and the faint stream of Arabic from the hijab mum. I close my eyes and drift.

Across the city, down south in Sylvania Waters, my mum is preparing to host a dinner for some friends. That curry leaf sapling she planted the year we moved in is now a flourishing tree. My dad, the brilliant, displaced surgeon, has been dead three years. My half-Indian children are taller than me, and more Australian than I will ever be. Time moves slow, then fast.

The American writer Anne Lamott once said, “We contain all the ages we have ever been.” I think we also contain all the geography of our lives — the rooms we have slept in, the houses we have grown up in, the gardens we have played in, the streets we have walked on, the cities we have lived in, the countries we have travelled in. Their silhouettes live on inside us, ghostly worlds we have passed through.

And maybe we contain all the beaches we’ve ever been on too.

This is an edited extract from Sharon Verghis’s A Tale of Three Beaches, from Growing up Indian in Australia, edited by Aarti Betigeri and published bv Black Inc ($32.99).

Cronulla Beach, December 1988

Brighton-Le-Sands, January 1990

Cronulla, December 11, 2005

Manly, January 15, 2023

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout