How Australian hip-hop duo REMI built a world of their own

Two musicians of African descent found each other in Melbourne and the result was the influential and innovative hip-hop duo REMI.

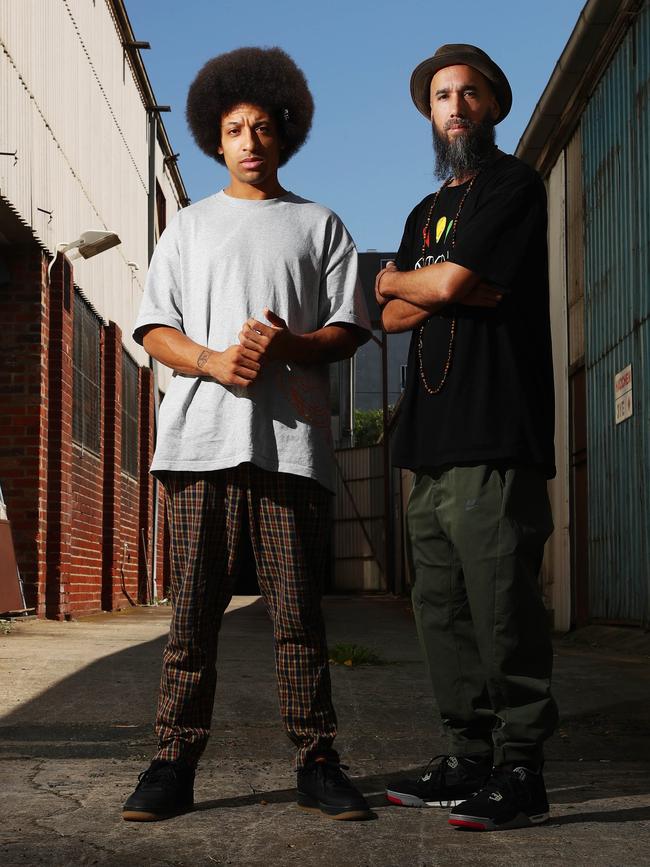

For most of the past decade they have spent making music together, Remi Kolawole and Justin Smith recorded at Smith’s home in Melbourne’s southeast. There, the unlikely friends — separated by 12 years and a tide of life experiences — wrote two albums and sundry singles as REMI, an all-caps title that sits comfortably over the hip-hop duo despite it also being the rapper’s first name. The moniker itself is telling: on stage and off, Kolawole is the exuberant Afro-coiffured motormouth upfront, attracting all the eyes and attention, while Smith is the laid-back, bald and bearded guy in the background, producing the music and performing the instrumentation that forms the bedrock for the rapper’s fiery vocal flow.

So it went for eight or so years: Smith — better known by his stage name, Sensible J — wrote the music and Kolawole wrote the words, and the pairing has fit together like lock and key. No matter that the drum kit barely fit in Smith’s spare bedroom: it sounded damn good in there. It sounded like home. The downside of living where you work, though, is the difficulty of untangling the two.

Any artist who dropped by the house inevitably would comment on how comfortable they felt there, sitting in the lounge room, writing lyrics, and the kitchen’s right there if you want a biscuit and a cup of tea. It was the opposite of the often sterile studio environment, where the daily rate is always at the back of artistic minds: if you don’t get a good vocal take done today, it’s going to cost another $400 tomorrow.

There was a cost to all that comfort, though. On a shared phone call from Melbourne, Smith tells Review, “It was a lot for my partner to have rappers constantly at our house, which wasn’t big enough for her to have her own space while there’s people here. When there was six people there, she would have to hang out with them. She never really complained, but I know that as a partner I’m expecting too much for her to hang out with all these loud-arse rappers.”

That’s all in the past: since May 2018, Smith and Kolawole have situated their musical base at a studio in a warehouse at Footscray. “That has definitely changed the dynamic because it means when we come here there’s intention: we’ve got to come here for a reason,” Kolawole says. “And I think that’s beautiful, but also a huge part of our process — and the entire creative process — is rolling up to a place, feeling super comfortable and saying, ‘Hey, let’s f..k around.’ And we can still do that, don’t get me wrong, but it’s less conducive to that kind of behaviour.”

Since moving to the Footscray studio, the pair have written, recorded and finessed their third album, Fried, which was held back from release for more than 12 months because of the pandemic. It now arrives five years after 2016’s Divas and Demons, a landmark work of deeply personal Australian hip-hop described in these pages as a compelling and surprising spectacle from beginning to end.

“It did so many amazing things for us,” Kolawole says of their second LP, which made its debut at No 10 on the ARIA chart. “For myself, it was the album I was always trying to write, ever since we started making music: to make a very introspective, super-cohesive record. Having that under your belt and knowing that you’ve achieved some of your creative goals, and then had that appreciated — it’s a really beautiful place to be. And it seems like it’s aged well: people are still bumping that shit, long term.”

Smith agrees. “Sonically, it flows, and everything that Rem wrote about is super honest and deep,” he says. “I feel like that’s what makes music classic, to me, where the artist at the time gives a snapshot of where they’re at — and as his friend, that’s exactly what he did on that record. You can’t go wrong with honest music.”

As strong and vital as that album was — and remains — its creation was coloured by Kolawole’s issues with mental illness and drug and alcohol abuse in his mid-20s, all of which he lays out frankly in songs such as Substance Therapy.

What was it like for Smith to watch his friend go through those experiences?

“Not fun, because if you take the music part of it away, it’s a friend soul-searching,” he replies. “I commend Rem for his confidence in putting that on record and speaking about it because that helps others who listen to it. It helps to talk about things, and with males often shying away from talking about their problems, I think it’s an important thing to do. As his friend, I commend him for having the guts to do that because I don’t know if I could.”

As for whether writing about his personal issues helped him, Kolawole is blunt. “Not really. It helped us financially because we were touring that album for years,” he says with a laugh.

“It’s cathartic to express; you go to a therapist and you express your feelings, and talk it out. But to move through what you’re going through? That takes reflection; that takes making positive choices for yourself. I feel like releasing the music is just one part of that.”

The pair met in 2011 through Smith’s partner, who worked a retail job alongside Kolawole.

“She always played amazing music over the system at work and I was rapping completely independently of J for six months before we started working together,” he says. “One day I told her that I was rapping, and she said, ‘Oh, you know my man makes beats?’ She played them on the system and they were crazy. I was so impressed because I hadn’t heard music like that before, and it didn’t sound easy: I didn’t understand the swing, the textures and the sound.”

Soon, Kolawole invited the couple to his parents’ house for dinner because he knew Smith was South African; Kolawole’s father is Nigerian, and he figured they might bond over African food and a shared love of hip-hop.

And that’s how it played out: the following week they began making music together, and by 2015 the pair had won the $30,000 Australian Music Prize for their debut album, Raw X Infinity.

“My whole life, there weren’t that many people into what I was into,” says Smith, who is 42. “In high school in the 1990s there was two people listening to hip-hop, me and one other person. So my mentality is, if I meet people into hip-hop, we need to be friends because it was a rare breed out here.

“Not any more, but back then. Back when I met Rem, I was making beats for two or three years before that, and didn’t know any MCs to work with, except for N’Fa [Jones, 1200 Techniques rapper]. And then Rem came along, and straight away this kid’s good for someone who’s barely done it.”

As for the 12-year gap between them, they each see it as an asset rather than a liability.

“I think in our case it works because we’re very different people,” Smith says. “It could be because of the age difference, or it might not be, but it’s a good balance: I’m not the wild energetic person who tells everyone my feelings because that would scare the f..king shit out of me, standing in a room full of people and telling them about how I am. But I like playing the drums, sitting up the back and being behind the scenes, so the balance works perfectly.”

As the men have grown together, after building a world of their own, their artistic kinship has only deepened. Both speak highly of how the other has developed their craft, and both see album No 3 as the latest — and perhaps final — evolution of a uniquely strong pairing and one of the most influential Australian hip-hop acts of the past decade.

Fried is out now via House of Beige Records.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout