Horseracing at heart of Gerald Murnane’s memoir Something for the Pain

Writer Gerald Murnane has always run his own race, but at 76 he has decided it’s time to broadcast it.

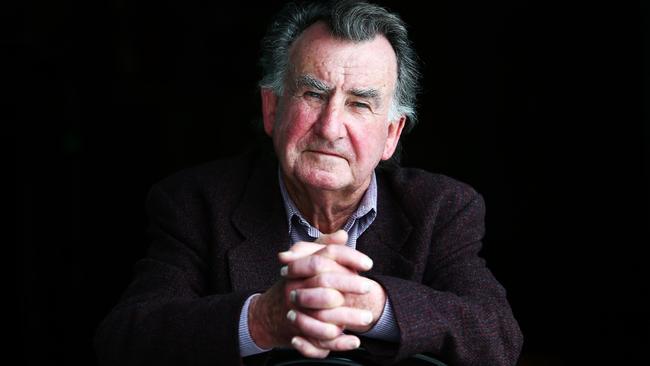

Gerald Murnane is midway through his first pot of beer when I, delayed by Melbourne traffic, walk into the near-empty bar in Federation Square. It’s just after 11am on a Thursday. In his brown tweed jacket, checked shirt and corduroy trousers, the 76-year-old writer — who is considered, along with poet Les Murray, to be Australia’s best chance for a second Nobel Prize in Literature — could be killing time before heading across the road to Flinders Street station to catch a train to an out-of-town race meeting.

Or do I only make that mental association because we are meeting to talk about the author’s new book, a memoir of his lifelong obsession — if obsession is strong enough a word — with horseracing? It’s the sort of speculation Murnane, an interior man, an explorer of the porous border between the real and the imagined, enjoys. “People ask me how much of my fiction is autobiographical,’’ he says in his considered way. “I say I don’t know but everything in my fiction has taken place in my mind. I have confined myself in my fiction to interpretation of events.’’

Murnane makes these observations later in the day, at a different bar. We drink a few beers through the day, at a couple of locations, but we keep ourselves tidy. Murnane, a home-brewer who doesn’t like wine, describes himself as a “controlled alcoholic”, and it’s the adjective that’s worth noting. In his life and work, control is important, in ways expansive and restrictive.

It’s his beautifully controlled prose, in novels such as The Plains,Inland and Barley Patch, to take three of the better known, works with few local comparisons, that underpins the Nobel speculation. When he and Murray, who are the same age, were considered contenders in 2010, the poet remarked of the novelist: “He’s a really literary writer. There’s a degree of shonk about most of us, but not him.’’ The Nobel ended up going to Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, and Australia’s long drought — Patrick White being our sole recipient in 1973 — continued.

Yet Murnane’s life-control means, among many other things, that he has never been on an aeroplane — the first sentence of his new book is: “Machinery and technology have always intimidated me’’ — an eccentricity in this day and age that limits his travel options should the Swedish Academy call. And before anyone suggests a nice cruise to Stockholm, Murnane has “always hated and feared the sea’’.

He laughs with approval when I joke that the main reason he has been prominent with the bookmakers who take bets on the Nobel is because his main champions, literary academic turned government adviser Imre Salusinszky and publisher Ivor Indyk, each place $5 on him and that’s enough to move the market. One has the impression he’d love nothing more than to be the subject of a gambling sting, the likes of which abound in the new book, Something for the Pain: A Memoir of the Turf. Yet there’s a bit of steeliness as he prepares his response. He’s a man who doesn’t make a lot of eye contact, but he does now.

“I have two thoughts about the Nobel prize. One is a nasty, vengeful thought, which is to win the Nobel prize would be a deserved punishment for all those judges of major literary awards who failed to give me first prize.’’ He laughs but he’s not completely joking.

“The second thought is that I have noticed over the years the winners of the Nobel are writers who would not be the agreed choice of the critics even in their own country, so it makes me think it would be possible. And I do have some sort of inside running as three or four of my books have been published in Sweden and been well received.’’

There are few writers who would see such potential upside in their undeserved obscurity, but Murnane also accepts his low profile has been a choice. The author of a dozen strikingly original, critically acclaimed works of fiction, essay and memoir, winner of the Patrick White Award and the Melbourne Prize for Literature, he is not a regular at writers festivals or other literary events; indeed he has rarely set foot outside Victoria. Almost needless to say, he has no social media profile; he doesn’t even have email. He does have a mobile phone, which he keeps in the boot of his car, making it mobile but not particularly useful.

Since his wife of more than 40 years, Catherine, died in early 2009 he has lived with one of his three adult sons in the small town of Goroke, population 623 at the most recent census, in Victoria’s Wimmera region. He’s secretary of the golf club (he plays off 27, a “hacker’s handicap”) and is involved in other civic activities. He recently judged a local yabby competition.

“They all know I’m a writer,’’ he says of his neighbours, “but I don’t think anyone has read or tried to read my books. I’m not insulting their literacy or anything like that; they’re just not interested and I don’t care. I’m popular and generally liked … well, I assume so anyway.’’

This is one of the intriguing aspects of Murnane’s character: despite all the avoidance of the modern world, he does not come across as reclusive by nature. Indeed on the couple of times we have met I would characterise his behaviour as gregarious, and this holds when we spend a few hours at a media preview of the National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition The Horse, where he happily chats to all and sundry, and is impressed to see socialite Susan Renouf, who owns a Melbourne Cup. He can’t wait to tell his sister, he says.

Later I say that there’s a passage in The Plains — a strange, hypnotic novel in which wealthy landowners entertain business proposals from various suitors, including a young filmmaker who tells the story — that reminds me of the author of that book. It’s also one of my favourite passages in literature:

My patron invites to his dusks some of the famous recluses of the plains. What can I say of them, when their aim is to say and do nothing that can be described as an achievement? Even the term ‘‘recluse’’ is hardly apt, since most of them will accept an invitation or receive a guest rather than attract notice by untoward aloofness.

Murnane is delighted by this. “Untoward aloofness,’’ he repeats, chuckling to himself.

He does hope Something for the Pain will introduce him to new readers, perhaps even in Goroke, where it was written (and where he has written two more yet-to-be-published novels), and that introduction will lead them to the earlier works that have earned him comparisons with Beckett (from Teju Cole, no less). “I have never tried to be fashionable and I never will,’’ he says. “But it would be satisfying if some young person read this book and said, ‘I’ll give his other ones a try’.’’

This memoir is Murnane’s most personal book, the most revealing of himself — “Yes, easily,’’ he agrees. “There’s nothing here that’s invented’’ — and I suspect he relishes that potential biographers or literary scholars wanting to winkle the facts behind the fiction will have to read a book about horseracing to do so.

He says his devotion to the sport of kings — for him it is more important than religion or philosophy, “a sort of higher vocation excusing us from engaging in the mundane” — has always raised eyebrows among those interested in his literary career. “They snigger,’’ he says with enthusiasm. “I’ve been sniggered at by journalists who’ve said, like they knew me as an author, ‘You’re interested in horseracing?’ Snigger, snigger. And I said, ‘Yeah’.’’

He says he loves the “primal scene” of the mounting yard — “not as Freud imagined it’’, he adds with surprising bawdiness — where the horses and their connections gather before each race. “I just love coming back to the fact that in the mounting yard anything is possible. It’s the world of the possible. Even the 50-1 horse, its owner thinks it has a chance.’’

He continues: “There’ll be people out there who’ll read this book and say, ‘That’s not the Gerald I know’. But let’s put it as bluntly as I can: I’m 76 years old and I feel less guarded and reluctant about revealing myself than I would have even 10 years ago, especially since the death of my wife.

“This was the easiest book I have ever written. I just sat down and wrote it, I didn’t hold back. All the things that matter are there: my wife, the racing game, my love of the betting … it wrote itself almost. It’s the only book of mine I’ve felt that with — most of them I have to organise and work out what goes where, but this just flowed out.’’

It wasn’t supposed to happen. Murnane’s parents, and particularly his gambler father Reginald, a racetrack regular and sometime trainer, discouraged their son from taking any interest in horseracing. To this day, Murnane has not sat on a horse, though that probably has as much to do with his general trepidation as anything else. But the boy growing up in Bendigo was spellbound by the sounds of the race broadcasts coming from the radio inside the house, the photographs and arcane information in The Sporting Globe and, perhaps most of all, the bright colours of the jockeys’ silks.

The last remains particularly important to Murnane. While I, in a party trick way, can recite Melbourne Cup winners going back to 1973, the first time I bet on the race, he can recall their jockeys, trainers and, vividly, their colours. The young Gerald would construct miniature racecourses and stud farms in the backyard, immersing himself in an imaginary world of racing that continues to this day. The racing game or antipodean archive, as he calls it, fills filing cabinets at his home: made-up horseraces with made-up horses, jockeys, trainers and owners, the results of which the author determines and meticulously documents. (He also has filing cabinets housing a literary archive covering all of his books, and a personal archive “that can’t be opened until several living people, my siblings and a couple of others, are all dead ... my whole private life will be revealed’’.

Murnane writes beautifully of his childhood self in his semi-autobiographical first novel, Tamarisk Row, published in 1974. In one lyrical passage the boy Clement names the horses for an imaginary race, the Gold Cup, and lists their colours: “Number one Monastery Garden, purple shade, solitudes of green, white sunlight, for the garden that Clement Killeaton suspects is just beyond the tall brick wall of his schoolyard … Number Nine, Captain Riflebird, a colour that wavers between green and purple enclosed with gold or bronze margins, for all the rare and gorgeous birds of Australia that Clement Killeaton only knows from books …’’

Murnane likens his relationship to colour to that of Marcel Proust’s narrator in Remembrance of Things Past, who “associates the vowel sounds in certain place names with distinctive colours or shades’’. A photograph of Proust (with whom Murnane has also been compared) was one of three pinned above his desk when he taught writing at a college of advanced education in Melbourne in the mid-1980s. The other two were of Emily Bronte and Bernborough, the Toowoomba tornado who thrilled racegoers in the mid-1940s and remains Murnane’s favourite horse. “Orange, purple sleeves, black cap,’’ he notes automatically.

Murnane goes further, contending Bernborough was a better horse than Phar Lap, the 30s champion generally regarded as the greatest galloper this country has seen. He mounts a case for Bernborough based on weights and measures, but concedes he is disadvantaged by not having seen Phar Lap in the flesh, as the great horse died in America in 1932, seven years before Murnane was born. When I tell him my grandfather saw both and loved Bernborough more than any other horse, he is all ears. When I recall the day my boyish inquiry as to who would win a hypothetical match race between the two was met with near disdain — “Phar Lap would have picked up Bernborough and carried him’’ — Murnane is willing to give ground: “Well, maybe Bernborough was as good as Phar Lap, or almost as good.’’

He also thinks his affinity for colour is “linked to my having no sense of smell’’. “I have trouble sometimes convincing people of this,’’ he writes, ‘‘but I have never smelled any sort of odour. I have held under my nose flowers said to be rich in fragrance and detected nothing.’’ It’s the sort of startling fact that pops up now and again in the memoir like a 100-1 winner. Ten pages further on we have this: “My own instinct was to respect or even to fear females.’’

Murnane speaks as he writes, with deliberation and a rhythmic use of repetition. When we first meet in that bar just after 11am on a Thursday, I say that reading Something for the Pain made me feel as though he and I had been separated at birth, albeit 25 years apart, as his passion for horseracing matched my own. And it is more than that: our experience of the sport feels not just similar but shared. Les Carlyon, who will review the memoir in Review next week, puts it with his usual exactness: “His memories remind you of your own.’’ Murnane is pleased that my interest in horseracing is multifaceted, and goes into a long, animated explanation as to why, one which gives the flavour of his speech.

“I said to someone this morning, my old friend, in fact he’s mentioned in the book, David Walton, an old schoolfriend, he’s an old racegoer, he’s met you, he said what sort of interview will it be? I said I’m hoping he’s more than just a punter, I said, we only just had time — this is you and I — to talk briefly over the phone and I got the impression, obviously wrong, that racing for you started with punting because for me it doesn’t. Punting is an aspect … in fact I was sitting on the toilet this morning thinking how I would lead into this — I always try to plan a bit, get the wheels turning — I said, you will of course be aware by now that racing for me is more associated with daydreams and memories rather than — I don’t have to go to the races, the races are there, wherever there is, in memory and in daydream and [here he vigorously taps on the table like Kevin Spacey in House of Cards, something he does a bit] I think that covers it. The invisible world is full of horseracing for me, it’s there in music, in colours, in imaginary racecourses that I’ve devised … and, yes, the actual world is great, it fills, it provides the raw material for this vast universe of racing that I seem to walk around in.’’

Yet when we continue the conversation later in the day at Young & Jackson’s hotel, which has the racing on television, it’s Murnane who has a handful of bets on the nondescript meetings at Gosford, Rockhampton and Sale in Victoria. “I know this sounds, at my age, a bit forlorn, but I’m experimenting with the latest of 375 systems,’’ he says with a rueful laugh as he scans the odds on the screens. I have to place his wagers at the automated betting machines. He’s also impressed that I can check the results of earlier races on my phone.

He bets $20 win on each of his selections, all of which fail to impress. I enjoy watching the races with him in companionable near-silence; from long experience we both can see how a horse is travelling and on this particular afternoon there’s no need to say much beyond, “No, it’s gone, no hope.’’ There’s always tomorrow.

So, the real world of racing is a daily part of Murnane’s life. He says when he’s asked why he’s never travelled he replies “jokingly — well, half-jokingly — that I couldn’t bear to go overseas because I wouldn’t know what was winning at Yarra Glen or Mornington or who was coming up for the spring carnival’’. He buys two newspapers every morning and the first page he turns to is the racing results. So it is that Something for the Pain is — aside from its other considerable attractions — a marvellous book about horseracing, one of the best this country has produced. It is full of fast and loose stories and colourful characters; there are strong opinions — fans of racecaller Bert Bryant had best skip the bit on him — and lots of laughs.

Indeed, it should be said, in case it’s not apparent, that Murnane is a funny writer and a humorous man, someone who seems to take a wry wonder in the unusual life he has chosen. He has a natural feel for the tangy vernacular of the turf. “Couldn’t train a pig to be dirty,’’ he says to me apropos a certain trainer. And there’s this recollection in the book of a certain jockey deliberately holding back his horse, to improve its odds for next time: “I’ve never seen a rider use less vigour … If [he] had sneezed in the straight the flashy chestnut would have won.’’

There’s also something more than a little melancholy about Something for the Pain, as the title hints (Murnane suggests in the opening chapter that this could be the name of a long-forgotten horse, but I wouldn’t bet on that). As a teenager, Murnane started going to the races with his father, but this time together was short: Reg died suddenly when Gerald was 20.

Murnane’s descriptions of his father are clear-eyed and loving. “He wore a bespoke suit and a gold-plated Rolex Prince watch and one or another of a collection of grey felt hats with peacock feathers in their bands, but he died with no assets to speak of and owing many thousands of dollars in today’s currency to his brothers and to who knows how many bookmakers that he welshed on, to put it bluntly.’’

There’s also a bittersweet story about a pact he made with his wife before she died, one that seems to be honoured at Caulfield racecourse one day not long after she has gone. Murnane, raised a Catholic, is not religious — “I could be an atheist but I’m not a materialist,’’ he offers out of the blue at one point — but believes in an “invisible world’’ that exists in tandem with our own. “I am convinced some part of me will survive death.’’

The book, which Murnane has structured with great care, concludes not with the exploits of a Bernborough or another great champion of his lifetime such as Tulloch or Kingston Town but on an ordinary Saturday at Flemington, “a day of drizzling rain’’, and the last race of an old New Zealand steeplechaser named Lord Pilate. The final sentences, short, powerful, empathetic, respectful, are deeply moving.

And then there is the image of that solitary little boy building racetracks in the dirt between the lavatory and the lilac tree; a boy who would grow to be a man who would turn his back resolutely to the coast, interested only in looking inward, to the plains and to himself.

When I ask Murnane if he has any regrets about this life, his answer is genuine and a little surprising: “My regrets are in an opposite direction,’’ he says. “I regret I haven’t been more assertive in my lifetime, that I haven’t made clear my view of the world, that I wasn’t confident enough to declare my true personality.’’

The races are over, for today at least, and it’s time to go. “I only wish,’’ Murnane says as we put on our coats, “I had more time to understand my own simple surroundings.’’

Something for the Pain: A Memoir of the Turf is published next week by Text Publishing.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout