Horror of war: Hiroshima and the Holocaust

Atrocities in the East and West are linked by the extraordinary figure of St Maximilian Kolbe, who died a martyr’s death at the hands of the Nazis.

To plenty of people it is outrageous to compare the Holocaust with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But hesitantly, unconfidently, and more often in Japan than anywhere else, writers and thinkers have considered the parallels between the two. The compelling testimony of survivors, the resonance of those famous place names, and the way in which they define a new era in human infamy, all of this reinforces a sense of connection – a recognition that, even if they were not equivalent, Auschwitz and Dachau, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were complementary horrors.

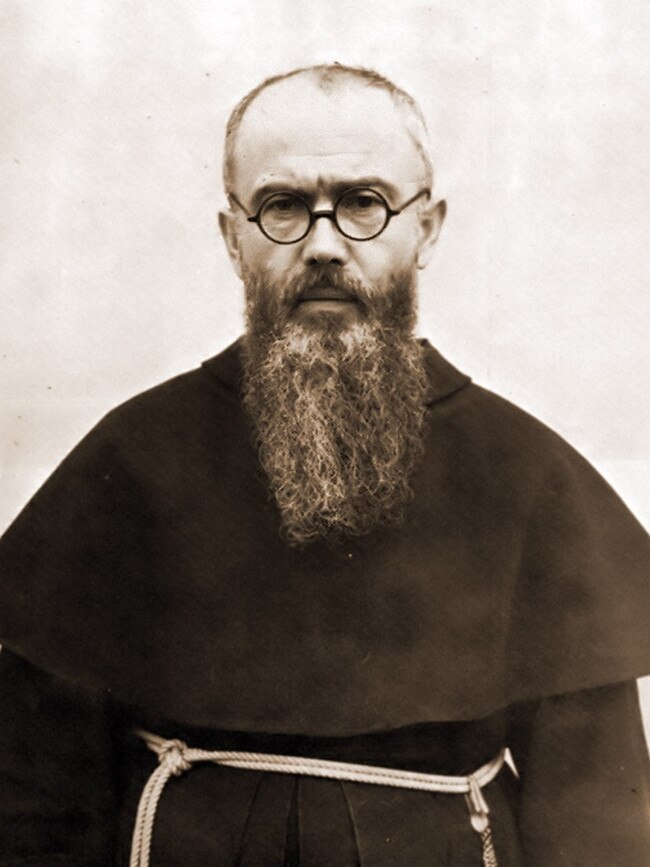

The Martyr and the Red Kimono by Naoko Abe, a Japanese journalist who lives in London, succeeds better than any book I know in capturing this mysterious affinity. It tells the story of three men – one famous and two obscure. The martyr of the title is St Maximilian Kolbe, a Franciscan friar who voluntarily took the place of a fellow Polish prisoner condemned to die in Auschwitz. Even before his martyrdom, he was a towering and terrifying figure in Roman Catholicism and Polish public life.

Despite suffering from tuberculosis, he founded the Army of the Immaculate, an international evangelical organisation, oversaw Poland’s biggest newspaper, founded what became the largest Christian publishing organisation in the world. Canonised in 1982, Pope John Paul II described him as “perhaps the brightest and most glittering figure to emerge from the darkness and degradation of the Nazi epoch”.

He was also an uncompromising disciplinarian, and his goal was world domination, not for a nation, but for the Virgin Mary.

“I want to elevate her ensign over all the centres for art, literature, theatre and film,” he wrote. “In short, I want to exalt her standard over the entire world.”

In the 1930s, he carried the flag to Asia, and established a Franciscan friary in Nagasaki, a historic centre of Japanese Christianity and the site of Urakami Cathedral, the largest church in Asia.

St Maximilian gave every sign of welcoming martyrdom, as well as recommending it to everyone else.

“Persecution purifies,” he assured his followers as the Nazis bore down on their monastery. “What a privilege to die as a knight in the crusade against evil, sealing our witness with our blood! This is what I wish for you and for myself.”

Accounts of his conduct in Auschwitz, many of them collated during the canonisation process, are inevitably idealised, but he seems to have been exemplary in love as well as courage. Before the war, his newspaper expressed the conventionally anti-Semitic views of the age, but in the camp Kolbe was as compassionate to Jews as to Catholics. He remained stubbornly alive until he was finished off with an injection of carbolic acid. He died in August 1941, aged 47.

In parallel with this is the story of a 17-year-old, Tomei Ozaki, who survived the bombing of Nagasaki. Whatever your view of the morality of bombing Hiroshima and its effect in hastening the Japanese surrender, the second bomb is difficult to justify. The original target, Kokura, was obscured by smoke from conventional bombing. By the time they reached Nagasaki, the B-29s were running out of fuel. In the grossest of ironies, the mission, commanded by a Catholic and blessed by a Catholic chaplain, missed the Mitsubishi shipyard and hit Urakami Cathedral; 70 per cent of Nagasaki’s Catholics were killed at a stroke.

Among them, Ozaki’s family.

It takes a skilled storyteller to do justice to such material, and Abe’s understated style serves her well in recounting the terrible details of the bombing’s aftermath: the living people with their skin burnt off; the boiling, raging sky; a child helplessly scrabbling to pull his mother out of a burning house. Some survivors “drenched in blood. Others dragged their legs or clasped their head in their hands. A man without an arm … A young woman (whose) guts burst out from an open wound.”

There is also the story of Masatoshi Asari, a teacher and botanist from Hokkaido who became the world’s leading expert on flowering cherry trees, sending hundreds of them across the world. I never imagined that I could be excited by descriptions of packing roots in sphagnum moss, but the account of Asari’s driven efforts to send saplings to Kolbe’s monastery (Will they clear customs? Will they survive the Polish winter?) is gripping.

By the end, these two old Japanese chaps are more alive on the page than the beloved saint. Where he had only immaculate certainties, they saw complexity and ambiguity. Ozaki could not stomach the doctrine, common among Nagasaki Catholics, that the bomb was God’s punishment for worldly sin. But he also rejected the cult of victimhood that ignores the historical context of the attack, the biggest difference between Nagasaki and Auschwitz. “We survivors needed to ask for forgiveness for what the Japanese had done at Pearl Harbor as well as from the Chinese and other Asian peoples,” he said. “We must not forget what we did as aggressors, not just talk about how miserable we are as atomic bomb survivors.”

The effort to yoke together three such disparate stories is only partly successful. The book peters out with Abe’s decision to try to find the symbolic cherry trees (almost none survived those winters). But it leaves behind it a moving glow of human connectedness, across the barriers of death and geography. “I feel that the deceased are somehow connected to the living,” Ozaki said. “Likewise, the living are linked to the dead. That’s what makes life so thrilling.”

The Times