Homage and away

Michelle de Kretser found kinship in the writing of expat Shirley Hazzard, who fled permanently in the early 60s.

‘Writing,” said Shirley Hazzard to an audience at Princeton in 1982 — using the term to encompass that transmission of human experience, thought and feeling we call literature — “is the only afterlife of which we have evidence.”

As an insight, this is both sharp and true. In a practical sense, it foregrounds the degree to which we are a story-making species. Having created narratives about the world that promise order, clarity and fixed horizons — whether labelled “culture” or “history” or “religion” or “law” — we proceed to inhabit them as if they were eternal verities. The ability to broadcast these across time frames longer than several generations may well be the defining fact of humankind, the ground of our collective success.

Yet it also speaks to the more intimate compact implicit in the act of reading — an acknowledgment that even in the midst of these social constructions we remain alone, essentially, and subject to individual mortality even as the world about us goes on.

This tension is where the novel comes into its own. As Michelle de Kretser suggests:

“There are moments when we recognise our inner selves in novels. It might be why we read them: to feel that we’re not floundering alone in the indifferent, midnight murk of the universe, for here is the lifeline of a kindred voice. We are saved, reassured.”

These are grand claims for a discipline of whose imminent extinction we are regularly warned and whose practice has apparently migrated to the screen, with its endless feed of instantaneously obsolete info-bites.

However, De Kretser’s ideal accords with the question posed and then answered by nature writer Annie Dillard decades ago. Why do we read, she asks, “if not in hope of beauty laid bare, life heightened and its deepest mystery probed?”.

Why are we reading if not in hope that the writer will magnify and dramatise our days, will illuminate and inspire us with wisdom, courage and the possibility of meaningfulness, and will press upon our minds the deepest mysteries, so we may feel again their majesty and power?

There are as many ways to read as there are readers. We can wrestle with a text as if only its submission to our intellect or will tame it. We can use it as a point of departure for our own thoughts and musings. Or we can read to lose ourselves, absolutely, in the style and consciousness of another.

De Kretser’s brief, brilliant and unapologetically traditional account of reading the novels, short stories and essays of Shirley Hazzard employs aspects of all three approaches and commits entirely to none of them. She holds in tension a critical intellect, fangirl enthusiasm, as well as personal experience drawn out or clarified by Hazzard’s work — a stylistically superb, humane, temperamentally liberal and sharp-witted author.

On Shirley Hazzard is, then, a short book with large claims to make. Its chief, though not its only virtue, is fervour for its subject. Not gushing for gushing’s sake — that vacuous strategy where adoration disguises a lack of understanding of the writer under review — but genuine, informed, carefully calibrated delight from a reader wholly worthy of the subject they address.

“Hazzard was the first Australian writer I read who looked outwards, away from Australia,” she concludes. “Her work spoke of places from which I had come and places to which I longed to go. It conjured cities and rooms: sociable spaces. Yet what she had to say was expansive, not enclosed — I felt enlarged by it, my view widened.

“It was reading as an affair of revelations and gifts.

“It fell like rain, greening my vision of Australian literature as a stony country where I would never feel at home. Splendour had entered the scene.”

The question of why Hazzard’s books elicit such a response in De Krester, herself an author of considerable gifts, forms the spine of an otherwise questing, speculative and impressionistic essay that darts from title to title, from memory to critique to appreciation in the space of a sentence.

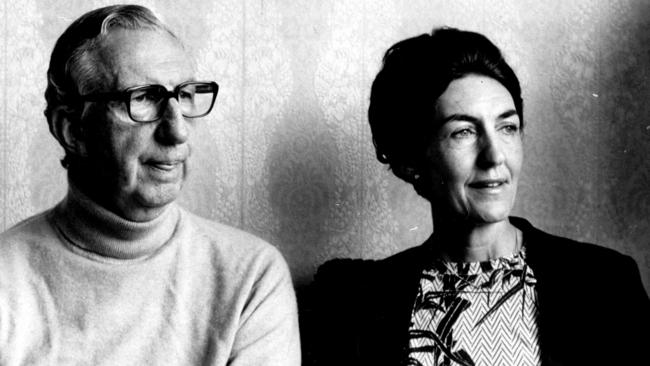

Shirley Hazzard was born in Australia in 1920, to a Welsh father and Scottish mother who had recently emigrated to the country. She was raised in Sydney and attended Sydney’s Queenwood School for girls in harbourside Mosman.

Hazzard felt an ambivalence towards her home country from early on. When her classes were moved to western Sydney at the outbreak of World War II, it was literature that increasingly became her refuge.

And when, in 1947, her father was posted to Hong Kong, she left with a sense of relief — only to be pulled back (the war interrupted her planned university study in what was still called the Far East), first to Australia and then to New Zealand, where her father was appointed a trade commissioner.

It was in New Zealand that Hazzard discovered the poetry and prose of Giacomo Leopardi — a touchstone figure. She learned Italian to read Leopardi in the original and began her steady and inexorable cultural turn towards the global north.

Initially that meant America, where she lived in New York, worked for the United Nations and published her early short stories, primarily in the pages of the New Yorker — then, after marrying biographer and translator Francis Steegmuller in 1963, the couple moved to Europe: to France and then her beloved Italy. She would tack between Europe and the US for the rest of her life.

Though she was a highly regarded author in the US, her Australian reception was coloured by her expatriation and her subject matter. For a nation busily establishing a national literature based on local stories, Hazzard was, like Christina Stead, irredeemably offshore and treasonously cosmopolitan.

Meanwhile, her stories, novels and non-fiction — though they never entirely eschewed antipodean characters or subject matter — were concerned with experiences (office life, expatriate experience, feminine subjectivity) which had little to offer masculine, rural, dun-coloured Ozlit.

For de Kretser, a woman of Dutch and Sri Lankan descent who landed with her family in Melbourne when she was 14 in 1972, the field of Australian literature as it was then configured was alien. She, too, found a home in literature from elsewhere; and she also lit out for the old world — Paris — once her primary studies were completed.

So, when the younger woman discovered Hazzard’s work, it provided her not just with another subtle, ironic, literary voice to enjoy: it offered her an alternative path as a writer. De Kretser writes of that first contact movingly and without critical cavil: “I remember exhilaration. And the rush of gratitude: that such writing existed, that it had come my way.”

On Shirley Hazzard mounts a defence of the author’s worth grounded in personal connection. But it expands as a celebration of Hazzard’s work on its own terms.

De Kretser admires the satirical edge of the senior writer’s early fiction, for instance, but ties it to deeper impulses: “A satirist always begins as an idealist. It could be otherwise: the ache that fuels critique.” What deepens Hazzard’s writing, de Kretser intuits, is precisely that resource which was in such short supply in 1940s Australia (at least the European strand): History.

“As history … entered Hazzard’s fiction, it oxygenated her work. It’s the difference between The Evening of the Holiday (Hazzard’s first novel, published in 1966) and The Bay of Noon (her second, appearing four years later). The characters of the latter are the products of a world recently convulsed by war, their lives forever imprinted with its journeys, conflicts, deaths. They’re yoked to history, to forces that exceed the self.

“I think,” she concludes with aphoristic brevity, “that history is the deep subject of Hazzard’s work.” If de Kretser attends respectfully to Hazzard’s stories, memoir, travel writing and non-fiction accounts of the utopian possibilities and real-world flaws of that organisation — the UN — which she knew from within, she reserves her full passion for those two later novels written two decades apart.

If all Hazzard’s fiction “poses the question asked by all serious art: how should a person live?”, then it is in The Transit of Venus, published in 1980, and in 2003’s The Great Fire, that such questions are asked best and with greatest complexity.

Indeed, de Kretser’s admiration for the first of these was only increased by a kind of delayed, readerly reaction. The first time she read the account of two Australian sisters and their emigration to England in the 1950s, she was still in thrall to the exotic Italian settings of Hazzard’s early novels.

It wasn’t until later in life that she returned to the book and discovered in its pages the kind of flawless narrative construction, constitutional melancholy borne up by quick wit and deepened by a devastating sense of fate, that raised the book above its familial works. If history was Hazzard’s deep subject, then that of love, so deftly explored in the lives of Caro and Grace Bell, was its necessary, humanising concomitant.

It speaks to the humility of de Kretser’s regard that she is willing to relish those qualities in Hazzard’s masterpiece that remain un-capturable. “One reason I value The Transit of Venus,” she writes, “is because it reminds me not to mistake the limits of my understanding for the limits of art.”

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

On Shirley Hazzard: Writers on Writers

By Michelle de Kretser. Black Inc, 112pp, $17.99 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout