Historical rascal Edward Hammond Hargraves is put in his place

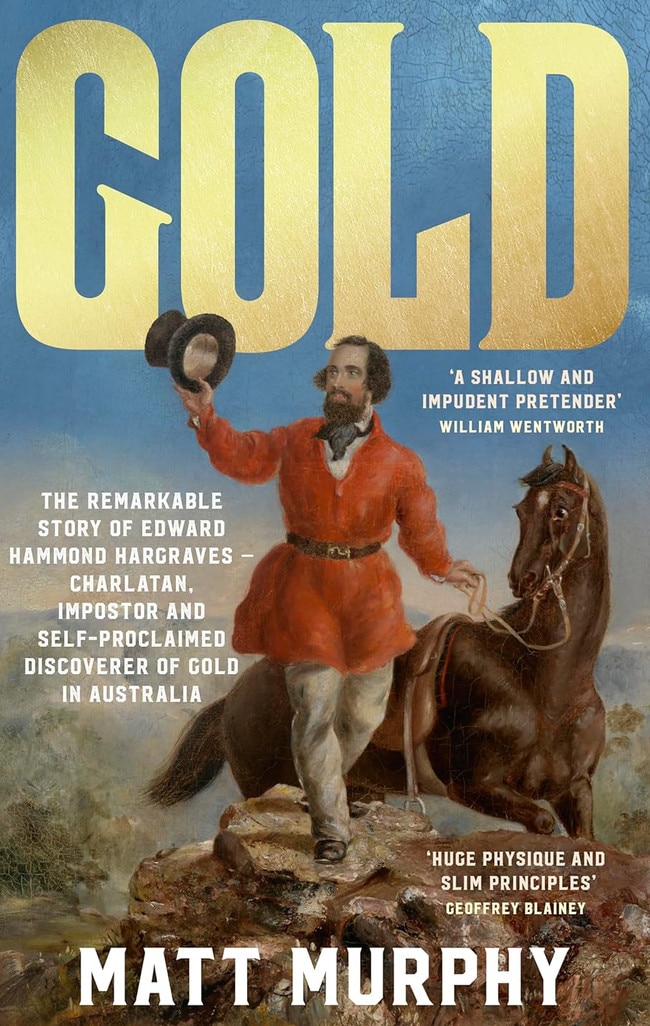

This splendid evisceration of a low-life bounder Edward Hammond Hargraves is a masterclass in the noble art of historical skewering.

Australia doesn’t celebrate her decorated bastards too well. We like our crooks to come from the gutters. Not like America, where high society is rich with villains and there are plenty of historians keen to throw dirt on the statues.

Frauds like Daniel Sickles, who murdered his wife’s lover in 1859 (he got off through America’s first use of “temporary insanity” as a defence), left his wife at home when, as a Democrat, he escorted a known prostitute into the New York State Assembly, and very nearly lost the Civil War for the Union by disobeying orders, taking counsel from his ego instead, at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Strangely, it was Australian author Thomas Keneally who spattered Sickles best in 2002’s American Scoundrel.

Then there’s Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon Church, a constitutional fraud and pants man who was magnificently undressed by Fawn Brodie in 1945’s No Man Knows My History (the chapter in which Joseph, having become enamoured with his wife’s buxom 16-year-old maid, emerges from bed to reveal God had come to him through the night to confess to having made a mistake – that married men can, in fact, have extramarital sex with balloon-chested virgins – is worth the cover price alone).

Gold is a rare Australian addition to this international catalogue of rewarded rascals. Those who suffered through the history of Australia’s Gold Rush in school will recognise the name Edward Hargraves. He discovered gold in Australia, so they reckon. He received the £10,000 prize from the government for having done so, as well as a £250 a month pension for life. There is a gold-plated penny with his face etched upon it, and a monument – a nice, firm phallic one – on the spot where Hargraves allegedly struck paydirt. And a heroic portrait of Hargraves, hat in the air, his suffering stead bringing up the rear (Hargraves weighed 114kg), still lives in the Mitchell Library.

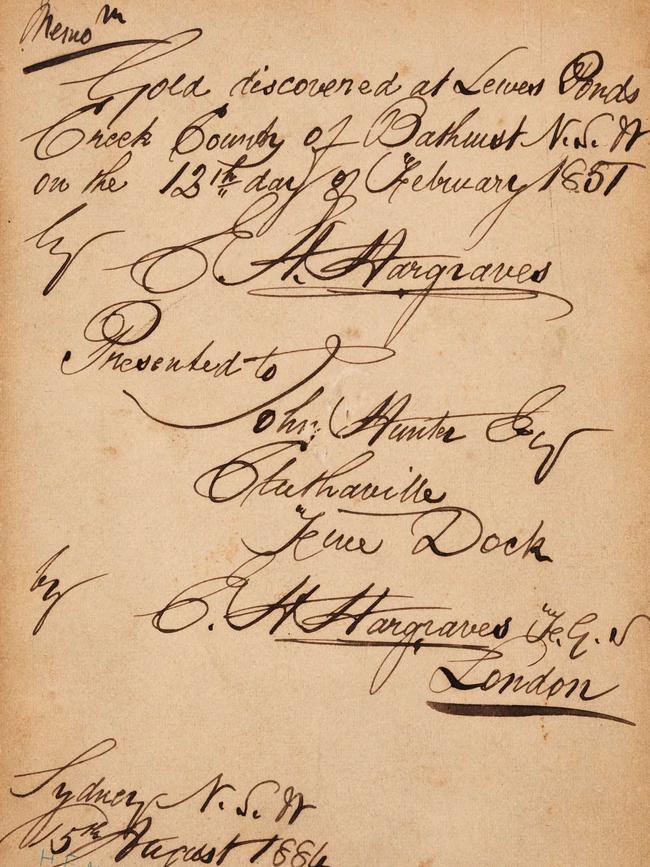

As Matt Murphy gleefully uncovers in Gold, the official story is a steaming pile of bulldust. Hargraves, along with fellow prospector John Lister, did scoop up about five specks of gold from the mud in Lewis Pond Creek near Bathurst, causing the excited Edward to stand and declare: “This is a memorable day in the history of New South Wales: I shall be a baronet, you will be knighted and my horse will be stuffed, put in a glass case, and sent to the British Museum!” What a wanker.

In truth, the specks were so small the lady of the nearby homestead needed a magnifying glass to see them. Undeterred by his microscopic “Eureka!”, Hargraves whipped his horse for Sydney, planting breathless stories in the press on the way and ultimately securing the government reward for himself, much to the chagrin of the team of four he’d left behind to do the hard yards, their only reward now coming from what they might find with their own hands and a good deal of discretion. Shame about the 300 prospectors who immediately descended on the area thanks to Hargraves’ self-promotion.

It’s true enough that Hargraves introduced his team to the pan-and-cradle method of gold prospecting, but he’d learned that during his time in America as one of the thousands of Australian desperados who’d flooded the California goldfields in the years prior to 1850.

Interestingly, Australians were not well regarded in the Americas, and Murphy cites a few examples of violent behaviour that might have given birth to the epithet “Sydney Ducks”, a derisive term that tarred the entire nationality of some 10,000 Australians, about 10 per cent of the population of San Francisco at the time. Vigilante groups rounded up Aussies and lynched them, seemingly for nothing more than having an accent.

Edward Hargraves did little to reverse this freelance ethnic cleansing. Having secured a place on an American team of prospectors going for gold, Edward found his niche – having realised the team needed pick-and-shovel men to do the backbreaking work, it was decided one man had to mind the tent. “No prizes for guessing which member of the party held down this important but unchallenging task,” Murphy writes.

It is said that miscreants can be spotted at the starting gate, and this seems true about Edward Hammond Hargraves. His early years saw him chased from one job to another, slithering from one entrepreneurial debacle to the next, each civic embarrassment only forgotten because the next one made for better gossip.

At a town meeting in the New South Wales hamlet of Gosford, he stood and declared his acumen had decreed not a single resident mentally fit to run for council. “As a result,” writes Murphy, “his name was mud throughout the district.”

Hargraves then took to the sea, on a journey that would ultimately offload him in California.

The fun of Gold is that Murphy hasn’t bothered playing the balanced historian. His research has told him this guy is a turd, and he tells it that way.

Before the book itself has even started, a page exists entitled: “Index of terms used to describe Edward Hargraves, official discoverer of gold in Australia.” A three-page list of slurs and insults follow, from MPs, journalists and men of the cloth. The first on the list is Murphy’s own: “Arse”, to be found, he instructs, on “Page 2”.

Put this book in schools.

Jack Marx lives in a mining town.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout