High-wire walker Philippe Petit takes his art to the edge of reason

A FILM about a high-wire walker is perfectly poised between fact and fiction.

YOU may have noticed that on Sunday nights ABC2, easily the most rewarding free-to-air digital channel, is the home of Sunday Best. This is the series' third season and the programming space really provides a place to celebrate the art and craft of some classic feature documentaries.

Among others screened this year there have been Richard Press's Bill Cunningham: New York, a delicately funny portrait of the veteran New York Times photographer; the remarkable Palestinian 5 Broken Cameras from Emad Burnat and Guy Davidi, an unparalleled record of life in the West Bank; and Pete McCormack's Facing Ali, which gives 10 brave souls who shared the ring with the great Muhammad a chance to speak and tell their stories.

It's a fascinating way to explore how great filmmakers working in nonfiction are exploring those increasingly blurred lines between reality and agenda documentary cinema, and the manner in which their search for truth drives them to persevere in an industry that doesn't always welcome them, let alone reward them handsomely.

It reveals, too, the way documentarians look to their films to give voice and dignity to those who are unheard, to right wrongs and preserve memory, but entertain us at the same time. They are the documentarians who are still making bold, stylistic choices more often associated with narrative storytelling than with traditional documentary filmmaking, and finding shrewd new ways to engage audiences.

"It's all movies for me," Werner Herzog, a master of both, famously said. "And besides, when you say documentaries, in my case, in most of these cases, [it] means feature film in disguise."

This Sunday, ABC2 brings us Man on Wire, the story of the spectacle that became known as "the artistic crime of the century". It's beguiling and beautiful, rich with many meanings and made with an astute self-awareness of the blurry lines crisscrossing cinema verite and fictional filmmaking.

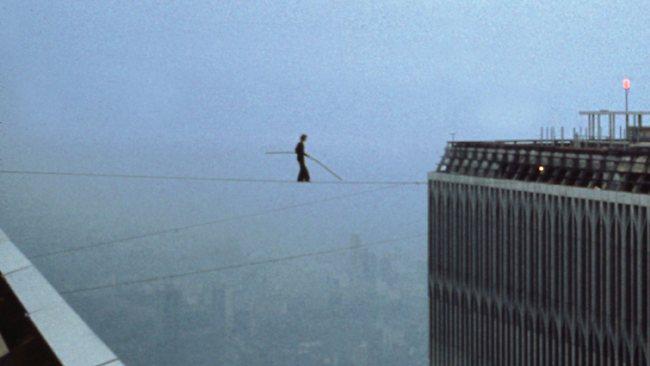

On August 7, 1974, a young Frenchman named Philippe Petit, a juggler and street clown, stepped out almost daintily on to a wire illegally rigged between the twin towers of New York's World Trade Centre, the world's tallest building at the time. He walked across the cable high in the sky for the next 45 minutes, the wire somehow anchored between the two rooftops at each end.

During the course of eight crossings he knelt in a kind of circus salute and lay down, "a daydreaming skywalker dialoguing with a hovering seagull", while 100,000 people gathered in agitation and wonder below. In an extraordinarily prophetic moment, an airliner flew above him between the towers.

Petit gave himself up to the waiting police, who were threatening to loosen the rope or use a helicopter to pull him off the wire. He was arrested, taken for a psychological evaluation and then to jail, before he was eventually released. The punishment demanded by New York's district attorney was that he juggle some apples before a group of children in Central Park.

Constructed with a kind of poetic underlay - superb music from Michael Nyman - this feature film, released in 2008, documents Petit's magical feat; its title is taken from the handwritten police report that led to his arrest.

Director James Marsh cleverly structures it like a thriller, deliberately echoing famous heist films such as Jules Dassin's Rififi or Ocean's Eleven.

Man on Wire is more of a docudrama than a traditional observed piece of reality in that actors are used and many key scenes are artfully re-enacted. For much of the time, it feels more fictional than it actually is, possibly more exciting, because Marsh has used those tricky conventions of narrative movies.

Petit plans the operation like a robbery, evaluating the chances of pulling it off and getting caught, and finding an inside man to facilitate the stunt. He has to find a way to somehow bypass the building's security, smuggle the heavy steel cable and rigging equipment into the towers, pass the wire between the rooftops and anchor it to withstand the winds and the swaying of the buildings.

Marsh juxtaposes rare footage of Petit's preparation, including interviews with his girlfriend, present-day talking-head interviews with his accomplices (some of whom weep as they remember), still photographs of the walk and archival footage beautifully edited by Jinx Godfrey with the expertly choreographed reconstructions. The destruction of the towers 27 years later is not mentioned in the film, but what happened never leaves your mind, even as you are awed by the magnificence of Petit's walk. It was "a gift", novelist Paul Auster said, "of astonishing, indelible beauty to New York".

Marsh commented on the film's release that as a New Yorker he wanted people always to think of Petit and his life-affirming performance when recalling the twin towers. "Life should be lived on the edge of life," the intrepid adventurer says in the movie.

"You have to exercise rebellion: to refuse to tape yourself to rules, to refuse your own success, to refuse to repeat yourself, to see every day, every year, every idea as a true challenge - and then you are going to live your life on a tightrope."

When the police questioned him afterwards, handcuffed to a chair, they asked, "Why did you do it?" Petit smiled up at them and said, "There is no why."

In this remarkable film, Marsh compellingly validates the meaning of the documentary as a form, with its complex arrangement of textures and meanings. The series also illustrates the way doco filmmakers have become increasingly bold at using the conventions of narrative fiction to engage audiences, stepping up to compete not only against the limitless videos generated for the internet and all those conflict-driven, scripted reality TV shows that fill the networks.

ONE of the best engineered of these is Alex Polizzi: The Fixer, presented again by the entrepreneurial Polizzi; it's a masterclass in how to create TV shows by giving reality a little sentimental twist after whipping up some conflict. Each week she arrives in her white limo to help British family firms that have reached breaking point, tackling their financial failures and especially their domestic dramas to guide them back on to the path to success. She knows what she's about too, darling. The 41-year-old award-winning hotelier Polizzi - brunette, sultry and bossy - became famous in Britain as the most recent host of reality show The Hotel Inspector, in which she was on a quest to salvage some of Britain's worst-run hotels and bed and breakfast establishments.

She comes from a long line of hoteliers: she is the granddaughter of Lord Forte and the niece of Rocco Forte, and her mother is hotel designer Olga Polizzi. She manages Devon's trendy Hotel Endsleigh, owned by her mother. So she also knows about family businesses, hers having had their own hassles.

Now she has left the down-at-heel pubs and exhausted country piles behind and taken a kind of left turn. She's waging a one-woman campaign to save these businesses, a sector vital to the British economy. The program is an amalgam of business improvement show, travel program and hard-core reality intervention series. As in The Hotel Inspector, the F-word is rarely absent as Polizzi poshly takes control, divinely uttered in those cut-glass, upper-crust vowels. No one on TV gets as much sensual relish out of uttering it either. It's such a pleasure just to watch her speak.

She not only understands the hospitality industry but appreciates that reality TV thrives on confrontation - and she's highly skilled at goading. Her belligerence and scorn - there's a comic touch of Joyce Grenfell as well as your disdainful dominatrix - seem to be highly welcomed by any middle-aged men she encounters in her shows. They look positively delighted to be chastised. It doesn't faze her; nothing does. Not even the loathing of British tabloid reviewers, who deride her as the cold-hearted consultant, TV's "angry helper", the cold-hearted consultant, "a plum-voiced Medusa clearly accustomed to turning left on aeroplanes".

In this first episode, Polizzi, oh-so-stylish in a tight-fitting short grey dress and billowing yellow scarf, has her work cut out trying to turn around the fortunes of Alf Onnie, a family-run curtain and blinds business in disenfranchised East Ham, London.

The large, shabby shop specialising in fabric and curtains is run by three brothers who, like the shop, are stuck in a time warp. It's the second poorest borough in Britain, recession has everyone downhearted and miserable, and the shop is positively Dickensian. It's wall-to-wall fabric chaos, the crowded displays lacking all rhyme and reason, curtains, towels, cushion covers and floor mats flowing out of baskets and boxes.

"It's like a storeroom that happens to be open to the public," says the straight-talking Polizzi, but frustratingly her attempts to modernise the shop and encourage the three brothers - Laurence, Kevin and Jeremy - to pitch for commercial made-to-measure curtain contracts (to end their reliance on budget-conscious locals) ends in a screaming match.

Polizzi tries to drag them into the 21st century with lessons in modern window-dressing and a photo shoot, but disaster strikes when they discover their premises are overrun with rats.

The Fixer is a very successful part of the now familiar factual, unscripted trend, using documentary-making skills within a well-delineated format (programmers call it formatted documentary). The idea is to create a situation and then film the seemingly spontaneous events generated by it.

The job, after all, is to engineer each situation to engage and satisfy emotionally invested viewers: the emotional backdrop might be constructed but the emotion still must have a foot, at least, in reality. It's much more difficult than it looks.

NEW drama The White Queen is as far removed from the crass machinations and the melodramatic stratagems of reality TV as can be imagined, and possibly from reality itself, too. And although it deals with protagonists who were the original participants in the first game of thrones, there are far fewer of the abrupt deaths and less of the rampaging sex and violence of that TV series.

This is a very stylish 10-part adaptation of Philippa Gregory's celebrated The Cousins' War series of historical romance novels, wonderfully directed in cinematic style by James Kent, the camerawork as breathtaking as the beauty of the female leads.

The White Queen begins in 1464 and takes place in the 20 years between the battles of Hexham and Bosworth. The War of the Roses has been raging for nine long years. The royal houses, Lancaster and York, are still fighting for the throne of England. The young Edward VI has deposed his cousin Henry VI and taken the throne by force, Henry is still at large, as is his hated queen, Margaret of Anjou. (We're told this at the start, which is just as well. This is complicated history: at a certain point in life you realise that understanding the War of the Roses is not high on your to-do list.)

The show features a lot of queens and handsome young kings, and it's difficult at the beginning to distinguish between the Beauforts, Nevilles and Woodvilles. It's obviously difficult for writer Emma Frost to "reanimate petrified forests of genealogy", as Kenneth Tynan remarked in reviewing Peter Hall's stage production of The War of the Roses, adapted from Shakespeare, but she tries, skilfully. Gregory, who is also executive producer of the series, has said she had the same problem writing the novels, as so many characters have the same names.

This is really the story of the devious women who gave birth to the Tudor dynasty and how their undervalued political skills brought about an end to the long, bloody struggle for the throne. I have no idea how accurate or revisionist it is, but it's a narrative that makes for seductive TV historical fiction.

These strong women have their work cut out, too, trying to survive the clashing enmities and temperamental incompatibilities of all those feudal potentates. It's understandable that witchcraft necessarily plays a grand role in all their scheming.

You know in the next few weeks there is going to be a lot of scheming and squabbling from these young men, together with their wives and progeny plotting and scheming, not in the background in this quasi-feminist version of history but in the foreground.

That the fate of England might have been decided by women and their devious power plays is certainly a lovely, intriguing idea to contemplate. The female cast is formidable, especially the luminous Rebecca Ferguson as Elizabeth Woodville, Janet McTeer as her intimidating mother, quite hypnotically regal, and Amanda Hale as Margaret Beaufort.

The series takes a while to develop, is rather sanitised - no diseases or deformities in sight and very pretty to look at - but it grows on you, perfect to record and view on a quiet Sunday afternoon with a glass of riesling.

In fact it's quite a relief from icy Scandinavian female cops with personality problems or American antiheroes embarking on the last chapters of their existential rides into the desert, waving automatic rifles at the skies.

Sunday Best: Man on Wire, Sunday, 8.30pm, ABC2

Alex Polizzi: The Fixer, Tuesday, 9.30pm, LifeStyle

The White Queen starts Thursday, September 5, 8.30pm, SoHo