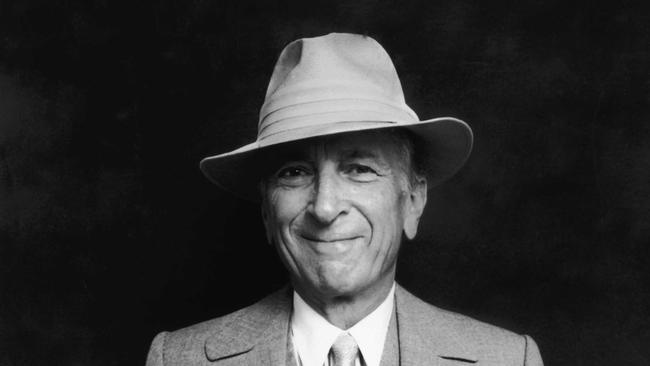

High Notes lets readers hang out with American writer Gay Talese

Gay Talese used the freedom of long-form reportage to experiment with the tools and techniques of fiction.

In the winter of 1965, Esquire magazine commissioned Gay Talese to write a profile of Frank Sinatra, in anticipation of the singer’s 50th birthday. But Ol’ Blue Eyes was stolidly uncooperative. He was unwell, short-fused and soul-weary. Undeterred, Talese interviewed his vast entourage instead, dozens of people from body-doubles to hairpiece-wranglers, to render the crooner entirely in silhouette.

The result, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”, is considered one of the greatest pieces of magazine writing. It is showcased in High Notes, a sleek survey of the American writer’s groundbreaking career.

The book features 13 pieces published between 1966 and 2011, many of which originally appeared in Esquire and The New Yorker, where Talese gained renown after leaving The New York Times. He was frustrated with the confines of daily reporting, how the need to be “plugged into the instant” ignored the narrative behind the news. “I wanted to write, not report,” he recalls. “Other reporters didn’t even see the story, they just saw their job.”

Alongside contemporaries such as Truman Capote, Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson and Norman Mailer, Talese used the freedom of long-form reportage to experiment with the tools and techniques of fiction.

In these pieces, people (often including the author) became characters, interactions became scenes and places became worlds. The corsetted language of the news was unloosed. What emerged was New Journalism (now known as creative nonfiction), an evocative combination of exhaustive research and literary craftsmanship.

High Notes celebrates Talese’s particular brand of intimate, vivid portraiture: immersive studies of the famous, infamous and unseen, tendered without moral judgment. The same inquisitive empathy is extended to mobsters and pornographers, socialites and the indigent, divas and newspapermen.

These are not conventional interviews but revelatory, cinematic vignettes. Lady Gaga and Tony Bennett record a duet and the air fizzes with musical chemistry; the doorman of a swanky New York apartment building conveniently fails to witness the violent street kidnapping of a mafia chief; an abrasive Russian soprano drags her luggage across Buenos Aires on a stolen hotel trolley.

Fronting the collection is Talese’s most personal and moving offering, a boyhood recollection of his Italian immigrant father: “an exacting tailor who presumed to possess the precise measure of my body and soul”.

Talese is very much a tailor’s son. At 85, he still wears the impeccable three-piece suits and fedoras his father favoured, and takes his notes on squares of shirt cardboard. And he has a tailor’s eye for detail, for the quiet importance of small perfections.

Talese’s meticulousness both delights and detracts. In small doses it adds wit and intimacy. He conjures a whole world in the changing (and unchanging) wallpaper of a beloved neighbourhood restaurant; Los Angeles is immediately brought to life when described as “a star land of little men and little women sliding in and out of convertibles in tense tight pants”.

But for Talese, everything is important, and as the details accrete, they weigh the work down. An intricate account of editorial power struggles at the “great gray goddess” of The New York Times exhausts with its catalogue of long-forgotten names, while an account of a young man’s erotic awakenings is so laborious it feels uncomfortably voyeuristic (emblematic, like much of Talese work, of a different era of sexual and gender politics).

Readers who are familiar with Talese may wonder at the purpose of High Notes as the anthology lacks new commentary or reflection. An introduction by Lee Gutkind adds praise but not insight. The substantial book excerpts are wobbly without the scaffolding of context, and following the controversy surrounding the release of Talese’s last book, The Voyeur’s Motel (in which a key source was exposed as unreliable), it would have been revealing to hear from him. But High Notes is a worthy introduction for new readers, a masterclass in people watching.

Talese has never been interested in trapping his subjects in a room in “the passive posture of a monologist”. Rather he practises what he calls the ‘‘art of hanging out’’.

“Wherever it is I try physically to be there in my role as a curious confidant, a trustworthy fellow traveler searching in their interior, seeking to discover, clarify, and finally to describe in words (my words) what they personify and how they think.”

Much of the insight is delivered indirectly, by looking around rather than at a subject. Talese is a poet of the periphery; he specialises in minor characters and hidden quirks.

As he reflects on the Sinatra interview: “What could he or would he have said (being among the most guarded of public figures) that would have revealed him better than an observing writer watching him in action, seeing him in stressful situations, listening and lingering along the sidelines of his life?”

This kind of networked immersion takes patience, time and investment, and stories about Talese’s passionate commitment are the stuff of myth (he once managed an erotic massage parlour for two years as research for a book about changing sexual mores).

For the Sinatra essay, he notoriously spent three months shadowing the singer in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and ran up more than $US5000 in expenses (in 1960s dollars).

The results are undeniable, there is a reason Talese has been required reading for a generation of journalism students, but it is hard to conceive of such extravagances in these hard-scrabble media times.

Beejay Silcox is a US-based Australian writer.

High Notes: Selected Writings

By Gay Talese

Introduction by Lee Gutkind

Bloomsbury, 269pp, $28