Hang on there Junior: David Malouf on novels, poems and memoirs

David Malouf refuses to be held ransom to writing novels or a memoir.

‘You reach a certain age where there is nothing more boring than your life story.” David Malouf, who will turn 85 in March, says that without a laugh or a sardonic raised eyebrow. He says it calmly. He’s being cheerfully serious, which is sort of his way.

So there you have it: Malouf, who has been writing for almost half a century, has no plans to write a memoir or autobiography. He also has no plans to write another novel, or collection of short stories. He started with poetry, in 1970 with Bicycle and Other Poems, and that’s where he plans to finish. His new collection, An Open Book, is out next week.

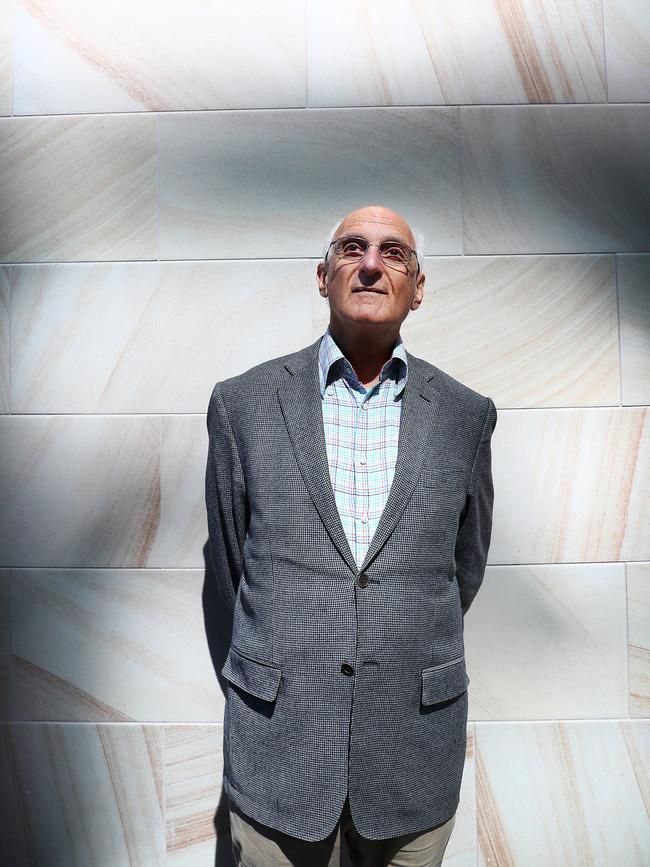

Malouf is the healthiest octogenarian I know. Admittedly, I don’t know that many. When we meet near his new apartment in central Sydney (he divides his time between it and an apartment on the Gold Coast), he is dapper in a striped shirt, chinos, a grey sports jacket and brown RM Williams boots. As we walk around a park to do the photographs, he light-foots it up and down the stairs. His skin is clear, his brown eyes are intelligent and warm.

After the photos, we go to a coffee shop to do the interview and then, via the Chippendale street in which he used to live, remembered in his writing, including the poem Visitation on Myrtle Street, to an Italian restaurant for lunch.

Malouf is a private man. He’s gay but articles about him in newspapers, magazines and so on say little about his private life, which is how he wants it to be. What I hope to do in what follows is have Malouf share a little bit about himself, “the walking and talking person”, as he puts it, who is not the same person as the “writer”.

First, though, some backstory. Malouf published four volumes of poetry before he worked out how to make a novel work. His 1975 fiction debut, J ohnno, is about a young man growing up in 1940s and 50s Queensland, as the author did. The narrator, Dante, has a close relationship with a classmate, Johnno. Both men have homosexual experiences.

Malouf has written nine novels. The Great World (1990), which spans both world wars and beyond, won the Miles Franklin Literary Award. His 1993 novel Remembering Babylon, an unusual take on colonial settlement, won the inaugural International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. His last novel, Ransom (2009), is a brutal yet tender re-imagining of a section of Homer’s The Iliad, in which the Trojan king, Priam, attempts to recover the body of his slain son, Hector, from the Greek warrior Achilles.

Malouf is too polite to say anything but I know, from previous conversations, that he was a little disappointed the book was ineligible for the Miles Franklin, under the ‘‘present Australian life’’ rule. Personally, I would include it in any list of the 10 best books of the past 10 years.

He has written short-story collections, books of poetry (his most recent being Earth Hour in 2014), works of nonfiction, one play, Blood Relations (1988), and libretti, including for the 1986 opera adaptation of Patrick White’s Voss.

Malouf was born in Brisbane. His father, a Lebanese Christian, left school at 12 and excelled at sports. It’s there in the opening lines of Johnno: “My father was one of the fittest men I have ever known. A great sportsman in his day, boxer, swimmer, amateur footballer, he was still bull-shouldered and hard even at 60 …”

His English-born mother was of Portuguese Jewish descent. She was the reader, the one who took her son into the world of books. In a delicate poem in the new collection, Kite, where toddler David is at the beach with his parents, his mother is “lost for the afternoon / in another century, drowned / like Ophelia in her book”. His father throws him into the sea and warns him, “You’re on your own now, / son”.

“I was two,’’ Malouf says. “That was my father’s idea of teaching you to swim, to throw you into the water and then just keep walking backwards.” I tell him my father, who was of Italian stock and who also left school at 12, did exactly the same to me.

The poem ends with “my father, even this late / in the piece, still standing clear, / but calmly, and with jovial / almost-approval, ‘Hang on there, / Junior, you’re doing well’.’’ It should sound soft and sweet but that “almost-approval” is hard.

David is one of Malouf’s middle names. He was named after his father, so that “Junior” is specific. “I was known as Junior, and other names,’’ he says. “My mother hardly ever called me by my first name. She called me all sorts of things. Nicodemus, Lord Muck, Lord Drack, Sunny Jim, whatever.”

He has one sister, Jill Phillips, who is two years younger and runs a Brisbane antique store. They are close now — “As you get older the only people who really understand you are your family, the people you grew up with” — but were not as kids. “I think I resented her coming in, as older kids tend to do.”

The “third person” in their sibling relationship was a nanny/cook/cleaner named Clarissa, who lived with the family. “It was just a conventional thing back then,’’ he says. “Everyone had a girl.” Even in adult life, Clarissa remained important. His sister saw her every week until she died, in 1993, and Malouf saw her whenever he was in Brisbane. Malouf was 30 when his father died and 36 when his mother died. He asks that I not print their names. He may have recently acquired a mobile phone, but he still writes on a typewriter and is cautious about how technology can invade one’s privacy.

His sister has two sons and one daughter, who between them have nine children aged 18-30. When I ask if any of them is a writer, Malouf smiles and looks over his glasses. “No.” Malouf likes children, especially ones like the three-year-old who chases birds, including an “elegant-awkward sacred ibis”, in the new poem The Prospect of Little Anon on an Inner-city Greensward, set in the park near his new home.

“When I look around, what gives me the greatest pleasure is, if not birds, then the three-year-olds with their confidence that the world is theirs.’’ He pauses. “It doesn’t last forever.”

Does he regret not having children of his own? He thinks about this for a while. “Probably not.” He explains that the life he chose to lead, including the time he quit his teaching job in Sydney and moved to a Tuscan village to write, would not have been possible as a parent. “I made a choice of that kind, and it has its profits and its losses.”

There have been romantic losses, too. Only one of the new poems, On the Move, 1968 , carries as dedication: for R.S. We are running it here today. The lines that jump out at me are: “I hear myself saying, ‘It’s only /time. We’ve got / this far, haven’t we?’ How far / was that, I wonder now. Holding / my breath, feeling the pressure // of your touch, the imagined / warmth, there in the street, / of your lips, did I miss something? / In your words? In / mine? In myself? In you? // I miss it still, / and daily, as I miss you … ”

In 1968, Malouf left England, where he had been for 10 years, teaching, and returned to Australia for a two-year position at the University of Sydney. He planned to stay only for that time, but “I got completely sucked into Australian life and in fact didn’t go back to England until 1972, which is when I wrote Johnno”.

I say the poem reads like one about a lost love. “Yes,” Malouf says. “A relationship that I thought would hang on for the two years I was away really, really got lost. I don’t think it was intentional on either side; it was just one of those ways in which time is its own course. That’s what that poem is about.”

I mention that kiss in the street was 50 years ago. Does he, at 84, in “another century” as he puts it, still miss that man he kissed?

“Yes. Isn’t that what we are looking at? The thing about it is that experiences, if they are powerful experiences, are what last. And when you put it in a poem, when you are actually doing the remembering, you’re right at the moment of the experience. That’s one of the things that drives poetry. Wordsworth calls it ‘recollection in tranquillity’. Well, it’s not quite that tranquil.’’

I ask if he will tell me who RS is. “No, I’m not going to say,’’ he replies. “No.”

■ ■ ■

When we talk about fellow poet Les Murray, Malouf says something that would not sound good in a radio interview. “Les is a complete whole.” It is, in fact, the highest praise. Malouf sees the work of every writer as a whole, a single structure rather than a collection of parts. It’s one of the reasons he does not plan to write any more fiction.

He notes Ernest Hemingway, who was “very, very, punctilious about his work”, being posthumously insulted by the publication of second-rate novels from manuscripts left behind after his suicide. That unwanted addition to his body of work was “a terrible thing to do”.

“Fiction takes a certain kind of energy and a certain kind of sustained interest in the detail of things that I think at a certain point you no longer have. I see people who go on writing right to the end of their life and you can actually see the way in which it gets thinner and has less pressure, less density.

“That’s something I don’t want to happen, so I’m quite happy to leave fiction. I think you ought to think very carefully before you add anything to your body of work. If it’s not going to amplify it in some way or challenge it in some way or change it in some way, if it’s just something you’re doing because you’re addicted to it, it’s not a good idea.’’

Does he, then, have a reliable Max Brod, someone who will burn his unpublished works when the day comes? “Yes, I do. Myself.” He reveals he has destroyed everything he does not want to see the light of day.

He thinks fiction overall “is in a bit of trouble”, with the digital revolution largely to blame. He notes the number of new writers, here and overseas, who set their novels before the 1990s. “They don’t want to deal with the world of technology, which has changed the relationship between people and made it difficult for fiction. Writers have lost faith in fiction and I think readers have lost faith in fiction. It’s a really weak area at the moment, whereas poetry, on the other hand, is very strong.”

The poems in An Open Book are set in a deliberate chronological order. The opening one, Parting, is about the birth of a child. “Parting is where / we began. Where we begin.” The final poems are a suite titled A Knee Bent to Longevity. When I note the darkness in one of these, Gravitas — “To become in time / a walking / coffin draped in black // in which younger livelier selves / are buried” — Malouf laughs. “Yes, gravitas is something you are supposed to have when you are old. Well, I think you should have lightness.”

Later, over lunch, I catch a bit of this lightness. We are talking about the theatre and I say the best performance I’ve seen on stage was Ralph Fiennes as Shakespeare’s Coriolanus. Malouf nods, but he’s not agreeing with me. “I remember Coriolanus, too,” he says. “It was 1959. Olivier.” Now there’s a reason to bend a knee to longevity.

While we are still at lunch, some more evaluations from the walking, talking David Malouf. The greatest stage actor he has seen is the German Ekkehard Schall (1930-2005), who he saw when the Berliner Ensemble, the group founded by Bertolt Brecht, came to London in the 1960s.

The greatest fiction writer of the 20th century is Marcel Proust. I tell Malouf I am planning to read In Search of Lost Time during an upcoming break and ask if the CK Scott Moncrieff translation is the best bet. He says the French original is the best, lighter and more fluid than any translation. Malouf is fluent in French, Italian and German. But he doesn’t show it off. When I tell him I’m going to have to start in English, he smiles and says that’s how he started too, and yes, with Moncrieff.

Shakespeare’s greatest play is not Coriolanus or Macbeth (my picks) or even Hamlet or King Lear, but A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It’s the only one, he says, where everything is entirely made up. Clive James is a remarkable Australian. His 1974 collection The Metropolitan Critic is a landmark work.

■ ■ ■

Talking about Clive James brings us to another topic: mortality. As someone who has been terminally ill for some time, James has used his writing, including his new epic poem, The River in the Sky, to make a sort of moral reckoning.

Malouf says he understands that, but he would prefer to go, when he does go, suddenly, without warning. “Going to sleep and not waking up is an easy way to go, though of course it’s hard on those around you. I think it’s easy to accept death if you have had a fortunate life. I don’t think survival is the important question. It is having lived fully in the world you live in.”

He does not believe in an afterlife, though he hopes he will be remembered, for his life and his work. On the latter, he jokes: “There’s no pre-nup agreement there! It is not guaranteed. It will be left to the judgment of others.”

Why no memoir then?

“Well, in its own way it’s already been done. There’s work in almost all my novels that draws directly on my own experience in various ways, and the poems do that over and over again. I feel I don’t need to do the formal thing of writing a memoir. It seems to me to be superfluous.”

Indeed, Malouf believes readers will learn more about him from his books than they would from a memoir. They may even learn things about him that he hasn’t quite caught on to yet himself. “My attitude to writing is that one of the reasons why you write is actually to let the writing reveal to you what your real life is and what your real identity is.

“I’ve over and over made the distinction between the writer and the walking and talking person, and the walking and talking person is a lot less interesting than the writer.

“People go to literary festivals thinking they are going to meet the real person, but they’ve already met the real person because the real person is in the writing. That’s where you are freest, that’s where you’re more willing to go out on a limb and test yourself. It’s the place where you make discoveries about yourself that surprise even you. What more is there?”

An Open Book, by David Malouf, is published by University of Queensland Press (90pp, $29.95 hardback). Malouf will discuss the book at events in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. Details: www.uqp.uq.edu.au/Events.aspx

-

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout